Scientists say Trump's border wall would devastate wildlife habitat

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/03/02/TXT-BorderWall-Richmond048.JPG)

HIDALGO, Texas — Muddy handprints cover the rusty, iron posts on this section of border fence in far South Texas. The 18-foot-tall barrier, which runs between a national wildlife refuge and a local nature center, ends abruptly less than a mile down the road. Still, somebody clearly thought it was best to cross here.

“This is probably one of the most visible places they could have climbed,” Scott Nicol, co-chair of the Sierra Club’s Borderlands Campaign, said before snapping photos of the handprints. “I don't know if they got caught or not, but they made it up and over for sure.”

There’s been a lot of debate about how effective the Bush-era barrier has been at keeping out illegal crossers and drug smugglers. Some data indicates the barriers have encouraged people to cross in places where there isn’t one. But the handprints show that a determined person can still easily scale it.

What the border fence has kept out instead, according to environmentalists, scientists and local officials, is wildlife. And the people who have spent decades acquiring and restoring border habitat say that if President Donald Trump makes good on his promise to turn the border fence into a continuous, 40-foot concrete wall, the situation for wildlife along the border — one of the most biodiverse areas in North America — will only get worse.

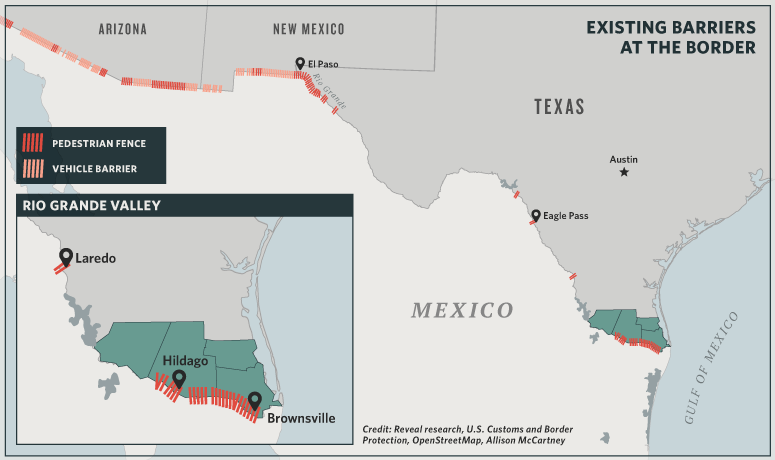

Right now, a mix of vehicle barriers and pedestrian fencing covers only about one-third of the nearly 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border. Even with all those gaps, experts say the barriers have made it harder for animals to find food, water and mates. Many of them, like jaguars, gray wolves and ocelots, are already endangered.

Aaron Flesch, a biologist at the University of Arizona, said most border animals are already squeezed into small, fragmented patches of habitat.

“If you just go and you cut movements off,” he said, “you can potentially destabilize these entire networks of population.”

Still, the impacts of the border fence on wildlife aren’t totally understood. That’s in large part because Congress let the U.S. Department of Homeland Security ignore all the environmental laws that would’ve required the agency to fully study how the barrier would affect wildlife.

Flesch and other scientists say the federal government also has made almost no research money available to support independent studies. Most of the studies that have been done are limited in scope, but their findings are pretty clear: Impeding animal movements puts them on a faster path to extinction.

Environmentalists and conservation groups say the border fence also has compromised the federal government’s own efforts to protect those vulnerable species, pitting the U.S. Department of Homeland Security against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The latter agency bought large tracts of land along the border decades ago and turned them into national wildlife refuges.

A spokeswoman for the Fish and Wildlife Service said the agency is not studying the environmental impacts of the proposed border wall and referred the Tribune to Customs and Border Patrol. That agency told the Tribune that “at this point we don’t have anything to share.”

A fast-tracked fence

When you envision the U.S.-Mexico border, you might think of a barren, dusty desert. But it actually ranks among the most biodiverse places in North America — particularly the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas. The Valley is home to some of the last remaining tracts of sabal palm forest in the country — a lush, subtropical ecosystem that is prime habitat for an endangered wild cat called the ocelot.

Two major migratory bird paths also converge in the region, and several tropical bird species there can’t be found anywhere else in the United States. More than 100 other endangered species may be impacted by construction of a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, according to an analysis of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data.

During his first presidential run, Obama vowed to review Bush’s directive to build the fence — which was still under construction when he took office — in part due to potential environmental impacts. That never happened, even after a presidential advisory committee urged him to study the issue before Homeland Security installed any more barrier segments.

Decades-old laws like the Endangered Species Act often tie up major federal projects for decades or thwart them altogether, but a 2005 security and immigration law that Congress passed gave Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff the power to waive all those regulations — which he did in 2008.

The existing border fence went up in just a few years. That left scientists scrambling to measure the impacts themselves — racing to try to measure animal movements before the fence was installed so they could compare them to what happened afterward.

Because the wall went up so quickly, “We didn’t have any good environmental studies of this area to establish a baseline,” said Laura Huffman, director of the Nature Conservancy’s Texas office. As a result, “it’s hard to comment on where we are today. And there was a lot of concern about that.”

The studies

At the 18-foot pedestrian fence in Hidalgo, the posts are positioned less than 2 inches apart — far too narrow for even small critters to squeeze through. Flesch’s research found that the fence also blocks the threatened pygmy owl, which can only fly a few feet above the ground.

Jesse Lasky, a biologist at Penn State University who studied the impacts of the fence on mammals, reptiles and amphibians, found that the U.S.-Mexico barrier reduced the range for some species by as much as 75 percent. Impacts were particularly acute on smaller populations of wildlife that occur in more specialized habitats like the endangered jaguarundi — another small wild cat.

“Mountain lions, jaguars, bobcats, javelinas, big horned sheep, deer, black bears — those animals often move far to find what they need,” he said, adding that a hardened border wall like the one Trump is proposing would be “substantially more threatening.”

Another study conducted in Arizona, published in 2014, used motion-sensitive cameras to monitor animal — and human — movement along the border. The researchers found that pumas and hog-nosed coons, or “coati,” were more likely to appear in places without a barrier. But human crossers appeared in equal numbers whether there was a barrier or not.

Constant noise and traffic from Border Patrol and other law enforcement activity is another threat to border wildlife, studies found. Even in areas where gaps in the fence could allow animals to get through, there are wide-open gravel roads constantly patrolled by border agents. At dusk, agents often set up mobile, generator-powered floodlights. That activity has steadily increased as border enforcement budgets have soared.

Flesch, the Arizona biologist, says all the gaps in the fence have definitely lessened environmental impacts; that’s especially true in Texas, where there is only 110 miles of it. Black bears, for example, have been able to continue their recent comeback in the Lone Star State after being hunted to near extinction, and even a few jaguars — more prevalent in Mexico — have been spotted in the United States in recent years.

Free movement of wildlife is especially important after droughts or natural disasters that can wipe out subpopulations, Flesch said.

“The only species we know that’s going to make it through the wall are people,” he added.

Competing agendas

For more than 70 years, state and federal government and conservation groups have been buying up land along the border to preserve habitat for endangered animals. Now, much of that same land is bisected by the border fence.

The section of the fence in Hidalgo is one of the clearest indications of those competing agendas. It sits on the edge of the Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge, located on land that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bought some 40 years ago. That means it’s federal property — so it became an easy target decades later when the Department of Homeland Security was looking for land to build the border fence.

In testimony to Congress in 2008, the former manager of that wildlife refuge, Ken Merritt, said the land “was thought of somewhat like low-hanging fruit.” That phrase had appeared in a Homeland Security PowerPoint presentation the previous year, referring to land the federal government already owned and therefore wouldn’t have to condemn to build the fence. (Merritt, who worked at the agency for 31 years, was forced into early retirement after refusing to sign off on the border fence plan.)

Ygnacio Garza, a former Brownsville mayor and chairman of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, summed it up this way: “You’ve spent money to build this environmental corridor, and now you’re gonna go right through the middle of it and put up a wall.”

The parks and wildlife commission, which also has spent decades acquiring land along the border to protect habitat, rebelled against the Bush administration’s border fence plan, too. According to a 2008 report in the Austin American-Statesman, park commissioners voted to reject an offer from the federal government to donate $105,000 to a nonprofit land trust in exchange for more than 2 acres of a state-owned wildlife management area where it wanted to build part of the fence.

"Construction of a border fence has impacts to fish and wildlife resources that could not adequately be compensated for by the offer of compensation," a department staffer said at the time.

But the state ultimately lost that battle. The federal government condemned the property, a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department spokesman said.

The federal government did do some things to try to help endangered species when it built the border fence, including rerouting some sections. At a segment near Brownsville that runs through a private nature preserve, there are small openings at the base of the fence every 500 feet or so meant to let small wild cats through — particularly the ocelot, whose numbers have dwindled to fewer than 100 in the United States.

Sonia Najera, grasslands manager for the Nature Conservancy, calls the openings “cat holes.” They’re the size of a piece of printer paper. She’s never seen an animal actually use one.

How are cats, or any other animals, supposed to find them?

“That’s a good question,” Najera said.

This story is a collaboration between The Texas Tribune and Reveal, a public radio show and podcast from The Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX.

Disclosure: The Nature Conservancy and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Kiah.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Neena_1.jpg)