When UT denied this valedictorian, she got it to change admissions rules

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/05/19/Madison_Mau_SK_TT.jpg)

FAYETTEVILLE — For most of her high school career, Madison Mau knew she wanted to attend the University of Texas at Austin, and practically everyone at her tiny rural high school was certain she could do it.

Mau is the valedictorian of her 10-student graduating class at Fayetteville High, on the west end of this 258-person town between Austin and Houston. She has earned perfect grades and compiled a list of extracurriculars too long to publish in full — Future Farmers of America president, National Honor Society president, class president, student council president and cross-country runner, to name a few.

But last fall, she was startled to learn that her future at UT-Austin wasn’t as automatic as it seemed. The top-ranked public university in the state is required by law to admit any student in the top 7 percent of his or her high school class. With only 10 students in Mau's graduating class, it was mathematically impossible for her to be in the top 7 percent.

After a brief moment of despair, Mau, 18, decided not to accept UT's denial. With the help of her parents, she made phone calls, wrote letters and implored her local legislators for help. She argued that it was unfair to turn her down because of her small school.

In February, UT-Austin took the unusual step of reversing its admissions decision for Mau and nine other small-school valedictorians.

“It’s a good feeling to know that I helped nine other people in the state that shouldn’t have got the treatment that they did,” she said.

Lifelong dream

Texas’ automatic admissions rule was devised in 1997 to help students like Mau who go to schools with fewer resources than the state's big suburban schools. As rural schools go, Fayetteville High is pretty competitive, but it doesn’t have enough students to offer Advanced Placement courses or other programs that look good on a college application.

Mau took advantage of every resource she could. She took multiple dual-credit courses through a nearby junior college and earned an A on each one.

Each morning, she drove down her parents’ mile-long dirt driveway — past the heifers, horses, rabbits, chickens, dogs and cats that live on their ranch — and then spent 20 minutes on country roads to get to class. The whole time, she was thinking about college. She applied to Texas Tech University, Texas A&M University, Baylor University and Rice University.

But her sights were always set on UT-Austin — and she was confident she’d get in.

“I saw that Longhorn logo and I was like, ‘I really, really like that. I want to be a Longhorn,’” she said. “I liked the vibe of campus, the feel, the look of the buildings.”

Her first hint that things wouldn’t work out the way she expected came a few months after she turned in her application. On Instagram and Facebook, she saw students posting pictures of their UT-Austin acceptance letters. Why hadn’t she, a valedictorian and supposed automatic admittee, received one, too?

She called the university and spoke with an assistant dean in the admissions office, who broke the news about the automatic admissions rule. Mau was stunned, but hung up with high hopes.

“She personally looked at my file and told me not to worry — I would get in,” Mau said.

In February, she received an e-mail from the university telling her to check her application at the school’s online admissions portal. Her heart raced as she opened it.

Then, she began to cry. It said UT-Austin couldn’t offer her a spot in the freshman class that fall.

“I was devastated,” she said. “That was where I wanted to go.”

She and her family took action. Her dad, a pilot, quickly notified her school’s superintendent. And the family wrote letters to Gov. Greg Abbott and the town’s two state legislators, Rep. Leighton Schubert, R-Caldwell, and Sen. Lois Kolkhorst, R-Brenham.

The lawmakers called the university and learned that nine other valedictorians across the state had been denied, too. They implored school officials to reverse course.

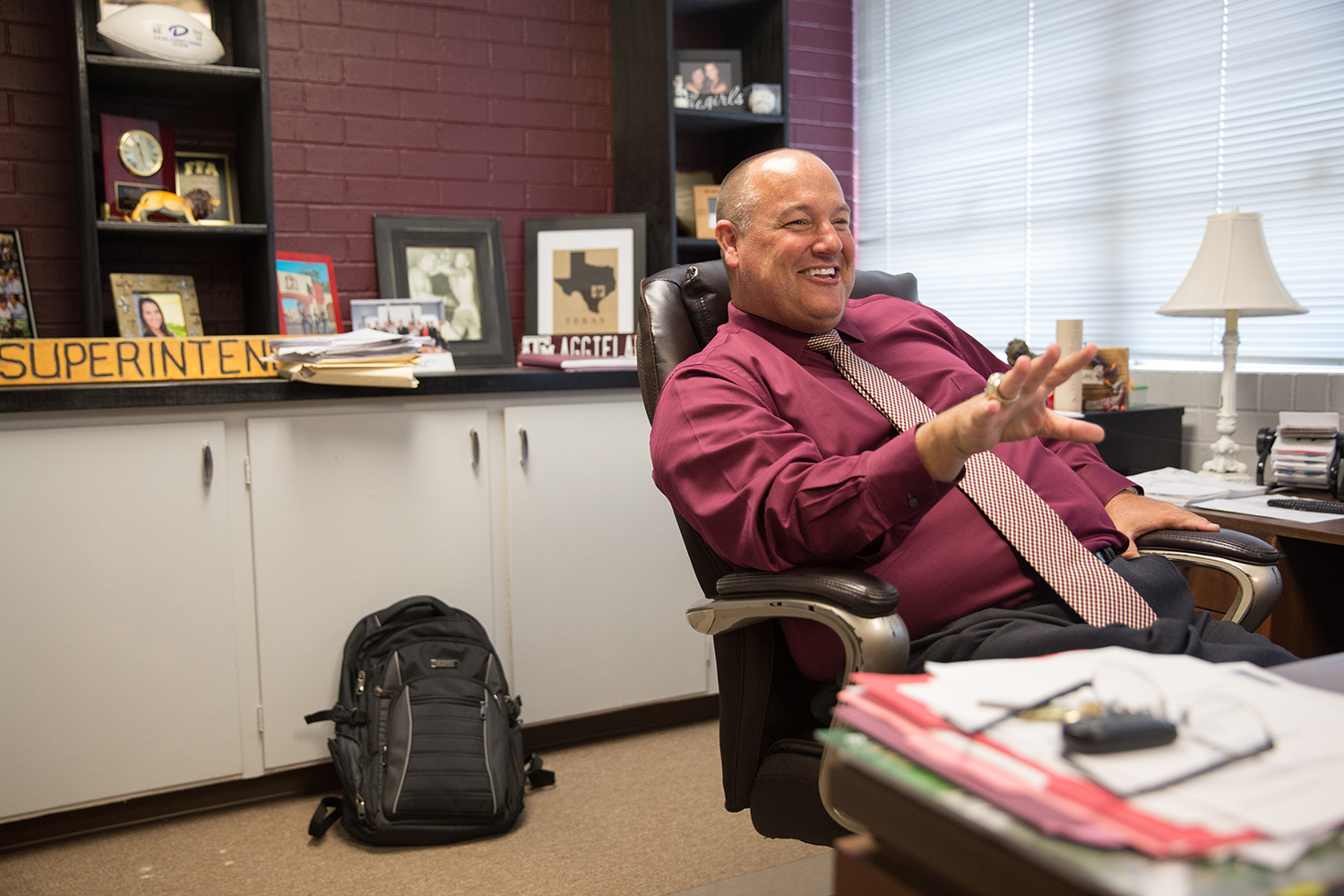

“We were just pointing out the fact that she has a number one on her transcript,” said Jeff Harvey, Fayetteville ISD’s superintendent. “She can’t magically conjure up five other students to put her in the top 7 percent.”

The university relented within days. It changed its policy to offer admission to all students who were at the top of their class as long as that class had at least two students, a spokesman said. All 10 students received e-mails telling them to re-check their admissions status.

When Mau opened her page, there was a message waiting: “Welcome to the Class of 2021.”

Still fighting

Three months after the reversal, Mau said she still has no idea who the other nine valedictorians are — or if they even know what happened. In an interview, she chuckled at the thought.

“Their dreams could have been UT and they found out that their dream school rejected them, and then later magically accepted them,” she said. “If that happened to me, I would be stoked.”

The ordeal convinced Mau to keep pushing for change. UT-Austin may have reversed course, but there was nothing stopping the university from changing its policies back. And students applying to other schools might run into the same problem.

In March, Schubert filed a bill in the Legislature seeking to require public universities in Texas to accept all valedictorians. Mau drove with Harvey, the superintendent, to Austin this month to testify in favor of it.

“This event was an injustice to the hard work of valedictorians across the state,” she told the committee. “We deserve to have our accomplishments acknowledged by state universities, regardless of class size.”

Harvey beamed as she spoke.

“These are the types of students we want,” he said later. “Someone who loves learning, loves others and is willing to work to help others be better as well. She has done that.”

After Mau’s testimony, the House Higher Education Committee unanimously approved the bill. But the legislation ended up dying in the full House a few days later. Representatives never had a chance to vote on it; it was killed along with dozens of other noncontroversial bills by members of the ultra-conservative Freedom Caucus in retribution for what they called "petty personal politics."

Schubert said he hasn’t given up and that he hopes he can tack the legislation onto another bill as an amendment before the session is over.

Meanwhile, Mau graduates from high school this week. Amid the confusion over her application to UT-Austin, she began to consider other options. She toured a couple more universities and researched the medical school acceptance rates of other pre-med programs. After some soul-searching, she reconsidered where she truly belonged.

She’ll be attending Texas A&M this fall.

Read related Tribune coverage:

- There were tears and shouting on the House floor when the Freedom Caucus helped kill dozens of bills this May.

- Attempts to repeal the Top 10 Percent Rule in Texas have fallen apart this legislative session.

Disclosure: The University of Texas, Texas Tech University, Texas A&M University, Baylor University and Rice University have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Matthew-Watkins-2024.png)