/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2013/06/13/TroubledWaters-Neches.jpg)

Troubled Waters

BEAUMONT — As the Neches River flows south toward a string of oil refineries and manufacturing plants in Southeast Texas, it winds through an area so ecologically diverse that the National Park Service runs a preserve called Big Thicket along its banks.

Despite recent spring rains, years of drought have caught up to the landscape. In 2011, the driest year in recorded Texas history, part of the river became so stagnant that it turned black.

“You see all those dead trees?” said Kirk Winemiller, who runs an aquatic ecology laboratory at Texas A&M University, pointing from a boat toward bald cypress trees that rose like ghosts along the bank. “They weren’t dead when we came out in 2011.”

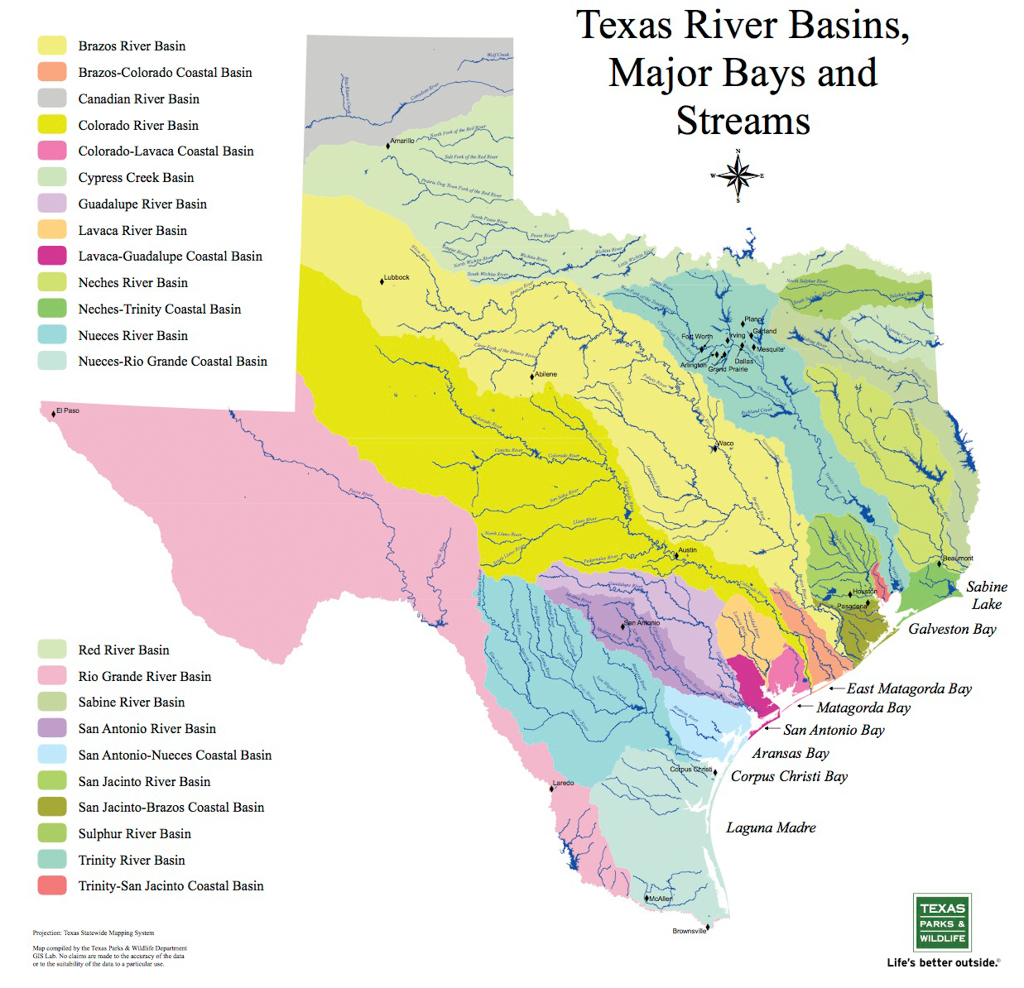

Like the Neches, other rivers across Texas have been severely tested by the long-running drought, which still blankets most of the state and comes on top of increasing demands for water from a growing population and industrial base. Average stream-flow measurements are well below normal, especially in western regions, prompting worries about increased salinity and the health of fish and plants. The environmental group American Rivers recently listed the San Saba River in the Hill Country as the country’s third-most-endangered river, because of heavy pumping by farmers.

Six years ago, the Texas government began an effort to manage the rivers’ health better. But environmental advocates fear that ecology still takes a back seat while the state frets about having enough water in the future for its growing cities. And climate change threatens further disruptions.

The Texas water plan, a wish list of water-supply projects like reservoirs that lawmakers are willing to spend $2 billion to finance, includes no projects to help fish and wildlife, said Myron Hess, who manages the Texas Water Program for the National Wildlife Federation.

“In my mind, it’s not acceptable to just say we’re not going to worry about what’s going to happen to the environment,” he said, noting that rivers offer economy-boosting activities like fishing, tourism and recreation.

Merry Klonower, a spokeswoman for the Texas Water Development Board, said that the state water plan did take water for the environment into account, because the water supply available was reduced.

Texas’ focus on the environmental health of its rivers increased in 2007, when state lawmakers passed a bill that created a process for studying and managing “environmental flows,” the amount of water needed to sustain the ecology of major river basins and bays.

The bill “represents one of the most groundbreaking environmental compromises” between Texas water suppliers and environmental groups, said Mary Kelly, who runs Parula, an environmental consulting firm in Austin, and was involved in the negotiations.

After a river basin is studied, scientists, farmers, citizens, water suppliers and other stakeholders make recommendations for its management. The input also takes future water needs of people and businesses into account. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state’s environmental agency, has the final say over how much water should flow down the river. Lawmakers provided $2 million in additional money for the process during the legislative session that concluded recently.

On a practical level, environmental flow standards can translate to the release of more water from reservoirs. This spring, for example, the agency that manages Texas’ Colorado River released a large amount of water — roughly equivalent to 35,000 Texas households’ annual use — from its reservoirs to aid the blue sucker, a threatened fish species, during its spawning season.

The agency has already issued flow standards for a number of rivers, including the Colorado, but it has more to cover, including the Rio Grande, the Brazos and the Nueces. Winemiller and Kelly (who serves on a science advisory committee in the flows process) say that the commission’s recommendations have often fallen short of scientific recommendations. So the ecological standards for rivers like the Neches, the Trinity and the Guadalupe are not as high as scientists (and even some stakeholders) think they should be.

“TCEQ’s adopted environmental flow standards include many of the science team and stakeholder recommendations,” Terry Clawson, an agency spokesman, said in an email.

A big concern hangs over this river-management process: if the state cannot manage its own rivers, the federal government could step in to help, amid concerns about endangered species.

A court case with potentially significant implications for Texas river management involves the whooping crane, an endangered bird that likes to spend winters on the Texas coast. In March, a federal district judge ruled that the environmental quality commission had failed to ensure that sufficient water to aid the whooping cranes was released down the Guadalupe and San Antonio Rivers. At least 23 cranes died as a result, the judge found.

Texas has appealed, and a federal appeals court will hear oral arguments in the case in August.

“Texas is very proud of their history of making largely autonomous water-permitting, water-use decisions,” said David Smith, a lawyer with the Austin firm Graves Dougherty Hearon & Moody. “You throw a couple of federal listed species in the mix, and all of a sudden you have those decisions being made with the specter of having federal oversight.”

In the coming years, Texas may encounter further endangered-species questions involving its waterways. For example, the federal government is expected to consider whether to list various species of freshwater mussels found in Texas rivers.

Meanwhile, human demands continue to put pressure on the rivers. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is seeking congressional approval to deepen the Sabine-Neches Waterway, downstream from Big Thicket near the Gulf of Mexico, to allow larger ships to reach the ports.

That could cause more saltwater to flow upriver, scientists say. The saltwater, which can harm swamp vegetation, is stopped by a barrier near Beaumont, which protects the city’s water supply.

When the river turned black two years ago, saltwater was a key factor — some of it left over from Hurricane Ike in 2008, according to Scott Hall, general manager of the Lower Neches Valley Authority, which manages the river and sells its water.

A paper mill has a permit to discharge an average of 65 million gallons of wastewater daily into the Neches not far below the barrier. Hall said in an email, however, that he believed “the water color was much more influenced by the high salt concentration than the paper mill effluent.”

This year, with the rains, the river system is “in pretty good shape,” he added.

This is the first in an occasional series of articles on the environmental health of Texas rivers. Find the rest of the stories and a map of the rivers in the series here.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0013_GalbraithKate.jpg)