In Dallas, "Big D" May No Longer Fit

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/TxTrib_Census_CalebBryantMiller10.jpg)

Big D may need a new nickname.

Despite a surging state population and double-digit growth rates in Austin, Fort Worth and San Antonio, the city of Dallas grew by a paltry 1 percent in the last decade, according to the new census figures — a rate lower than any of the 20 largest cities in Texas. Dallas County fared little better: Its 6.7 percent growth rate was dwarfed by the four other most-populous Texas counties, which each saw more than 20 percent growth.

City and county officials blame the low growth on Dallas’ topography: The third-largest city in Texas is simply built out. With little empty land ripe for new development, they say, the bulk of the growth must naturally be outside the county line — that is, until their efforts to lure business professionals and retiring suburbanites into a newly remodeled, newly trendy downtown fully pay off.

“We may not have the same population opportunities, but we’re focusing on the economic side of that,” said Tom Leppert, the exiting mayor of Dallas. “We’re bringing a lot of business in, seeing a real resurgence in the downtown area. We’ve positioned ourselves very well for the future.”

But critics suggest Dallas’ larger-than-life image may be shrinking for another reason. They argue that officials’ lack of investment in public schools, streets, parks and pools — the real-world priorities outside of the city’s highbrow Arts District, with its cultural monuments designed by the hottest “starchitects” (Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, I.M. Pei, Renzo Piano), and soon-to-be sky-high Santiago Calatrava “signature” bridges — is sending white families and middle-class minorities fleeing for the suburbs. The result, they say, is an inner city that is increasingly Hispanic, less educated and poor.

“That means property values are likely to decline, and with property values, tax revenues,” said Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Dallas’ Southern Methodist University. “At the end of the day, when a family has to make a choice between living in Dallas, close to its cultural amenities, or having better infrastructure, schools, libraries and pools in the suburbs, they’re not going to choose Dallas.”

The city’s low growth is no reflection on Texas. The state’s overall population increased by about 20 percent in the last decade, more than twice the national level. All of Texas’ urban counties, save Dallas County, matched or exceeded the state’s growth rate. Meanwhile, the city of Dallas gained just 9,000 residents since 2000 — compared to Fort Worth’s 200,000-resident increase and San Antonio’s 182,000 boost.

Steve Murdock, a professor at Rice University and a former U.S. Census Bureau director, said it is routine for large central-city counties to experience declines or modest growth at the expense of more suburban areas. For years, he said, Dallas and Houston seemed to buck the trend. That dynamic could be changing now, with Dallas’ almost negligible population increase and Houston’s modest 7.5 percent growth. “When you look at Dallas County, it stands out in terms of slow growth,” he said.

And Dallas is in a position to fare worse than Houston from a population standpoint, Murdock said, because the city is older and geographically smaller, and has fewer places to build the sprawling residential developments possible in the suburbs.

Mike Moncrief, the mayor of Fort Worth, said one of the big reasons for his city’s explosive growth is that Dallas is largely built out, and development is moving from east to west. While Dallas County can “only continue to build density,” he said, its neighbors, including Tarrant County, have room to grow.

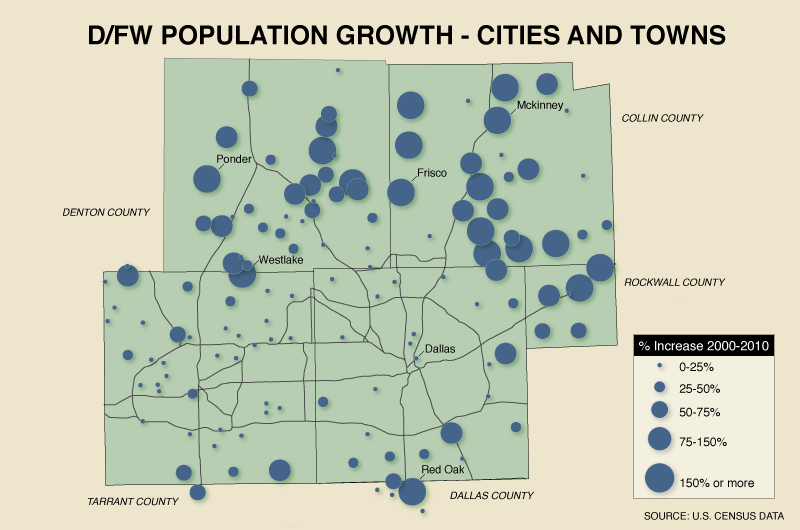

Indeed, neighboring Collin and Denton counties grew by 59 percent and 53 percent, respectively; nearby Rockwall County grew by more than 80 percent, and is home to Fate, the biggest boomtown in Texas’s 2010 census count (it grew 1,100 percent). Statewide, four dozen cities and towns more than doubled their populations, and more than half were in the Dallas-Fort Worth region. “It’s phenomenal,” Murdock said, referencing one such city, McKinney. “You find growth rates there that make you stand in awe.”

But these numbers also back up the assertion that white suburban migration is contributing to Dallas’ population stagnation — and could potentially negatively affect the region’s tax base. Dallas County’s white population fell by about 2 percent, or 27,000 residents, in the last decade. The four other most-populous counties in Texas saw double-digit increases in their white residents.

And while the city of Dallas’ white population increased by less than 1 percent, its Hispanic population surged by 20 percent, and its black population declined — the result of the migration of black middle-class families to the region’s suburbs. That explains why the percentage of Hispanics in the overall city population increased, to 42 percent in 2010 from 35 percent in 2000. The fear, Jillson said, is that “because education levels for Hispanics and incomes earned for Hispanics are lower than Anglos', it’s going to mean an overall decline in county prosperity.”

Elba Garcia, a Dallas County commissioner, said that anytime a county has a low level of growth, it is a challenge for the tax base — regardless of the ethnic breakdown of the population. She said the spike in the region’s Hispanic population would likely translate to more Hispanic representation in the state’s redistricting process.

But the population decrease inside the city also means that urban residents could lose some sway in the Texas House. Several incumbent members of the chamber represent districts that did not keep pace with the population of neighboring suburban districts, and they may be consolidated.

“The fact that we’re seeing so much growth through the area speaks well for the region,” Garcia said. “Does it present some challenges? Obviously. But I believe it eventually equalizes.”

Leppert — who on Friday resigned his office four months early amid speculation he will run for the U.S. Senate in 2012 — does, too. And he thinks the city’s emphasis on keeping taxes low, dramatically reducing the crime rate and attracting major employers to downtown will reap major rewards — and keep the “Big D” moniker meaningful.

Jillson’s not so sure: “Texans are used to living on dramatic claims and hype that mask the underlying reality,” he said. “But it’s getting to be pretty thin gruel.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0016_StilesMatt800.jpg)