Disabled students restrained, injured in public schools

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/103009_restraints_go.jpeg)

AUSTIN – Texas educators forcibly pinned down students with disabilities more than 18,000 times in the last school year, sometimes injuring them in the process.

A Texas Tribune review of state data shows public school educators used so-called “physical restraints” – a tool to control or discipline students with disabilities – roughly 100 times a day during the 2007-08 school year.

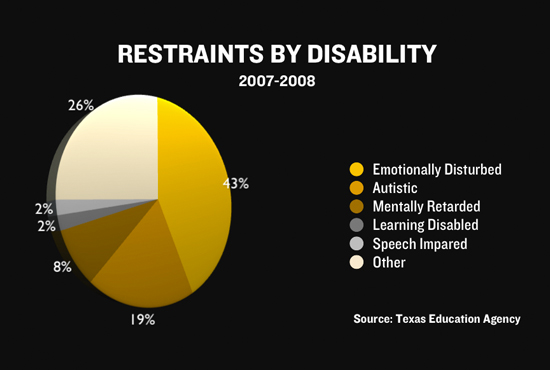

That year, school staff restrained four of every 100 special education students, with some students being restrained dozens of times. More than 40 percent of restrained youth suffered from emotional problems like post-traumatic stress disorder; nearly 20 percent were autistic.

Educators say restraints are sometimes the only way to prevent disasters. They point to the September 2009 case of a 16-year-old Tyler special education student who fatally stabbed his music teacher in a classroom.

But disability rights advocates say the numbers point to a crisis in Texas special education. They say teachers are resorting to physical restraints because they aren’t properly trained to manage their students’ disabilities – posing a threat to vulnerable children and to themselves.

Their concerns were echoed in Washington this spring, where a federal agency exposed thousands of restraints – including several deaths – of special education students in schools nationwide. In many cases, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found restraints were performed on children who weren’t physically aggressive, and by teachers who weren’t trained to use them.

|

“It’s a dangerous intervention, both for students and for staff,” said Steve Elliot, an attorney for Advocacy Inc., the state’s federally funded abuse watchdog group. “We’ve had students die in Texas because of restraints, and staff members report injuries. There are less intrusive ways to intervene when inappropriate behavior arises.”

Educators say restraints are only used as a last resort, when all other methods to intervene have failed. When properly used, they immobilize students who are a physical danger to themselves or their classmates without injuring them.

But even with proper training, they’re risky. Restraints can easily lead to scrapes, bruises and broken bones, and too much chest pressure can block air to the lungs.

Between 2002 and 2004, a profoundly disabled teenager was restrained 40 times at her Kemp, Texas high school; in one incident, her family says, educators broke a $100,000 device surgically implanted in the girl to prevent seizures.

In 2004, an emotionally disturbed boy trying to leave the classroom for lunch died of suffocation after his Killeen teacher sat on him to restrain him.

The Texas school districts with the highest restraint rates say there’s no crisis: Some say they’ve been over-reporting the numbers; others say they have tougher special education populations than their peers. But many say they’ve been working in the last year to improve training and provide teachers with alternative strategies, and that their restraint numbers are dropping steadily.

“Our numbers were very high,” acknowledged Austin ISD special education director Janna Lilly. The district saw its restraints drop from 1,007 to 790 in the last two years after it hired a full-time student aggression specialist and started focusing on “positive behavior supports” -- techniques to calm students without getting physical.

“We’re not out of the woods,” Lilly said, “but our numbers are now lower than other districts with fewer special education students.”

Officials with the Texas Education Agency say they started collecting special education restraint data and training teachers in restraint alternatives in 2004, after the Killeen boy’s restraint death. School districts are not required to track restraints of students in the general education population.

“There wouldn’t have been all of this work done if this wasn’t a concern,” said Kathy Clayton, the state director of special education. “There’s a heightened awareness now.”

But she said there’s no way to tell if Texas’ numbers are low or high. Only three other states record restraint data, and they don’t record it the same way Texas does. And she said even Texas’ numbers may be exaggerated because of inconsistencies in the way districts have reported restraints. The state doesn’t keep data on restraint-related injuries.

“It makes it very difficult to be able to look at any trends,” she said.

Advocates for people with disabilities say the comparison isn't that tough to make.

California – which has 2 million more public school students than Texas – reported about 14,000 instances of restraint, seclusion, or other emergency interventions during the 2007-08 school year. Texas had 18,000 instances of restraint alone.

Texas’ numbers could also be low. They’re self-reported by the school districts, the advocates say, and don’t account for the many restraints performed by on-campus peace officers and other school district police, who aren’t required to report to the state.

“Because they don’t have to report it, school districts will often call in a police officer to make a restraint, instead of having the teacher do it,” said Deborah Fowler, an attorney with the legal advocacy group Texas Appleseed.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)