Are You Ready for Some Football?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/allenhighschoolcollage_.jpg)

Drive north of Dallas on Highway 75 and after about 25 miles you'll find Allen, where a suburb that grew up in the boom of the late-'90s telecommunications juggernaut is just entering its prime. Down a road framed by tennis courts and endless parking lots, on the other side of a traffic circle, is an imposing red brick school building that dominates an otherwise bleached landscape of oatmeal-colored sidewalk, gray pavement and drab green athletic fields. On a day near the end of the school year, the heat of midsummer is already in the air, interrupted only briefly by gusts of wind that blow forcefully across the flat North Texas terrain of Collin County.

This is Allen High School, home of the Eagles and a study in bigness: a 5,000-student campus, with a 650-member marching band, the nation’s largest, supporting a football team that draws 8,000 fans to away games. And now — the pinnacle of the community’s collection of suburban spoils — Allen will break ground on an 18,000-seat palace of a stadium. Though only the fifth-largest high school football stadium in Texas, it’s the largest that will be occupied by a single team. Of course, it carries a big price tag: $60 million, approved as part of a $120 million bond initiative that also includes new performing arts and transportation service centers. Voters approved the measure 63 percent to 37 percent in 2009, a year after the Eagles won their first state football championship.

Still, Allen High head football coach Tom Westerberg says he “wouldn't say that football is the main thing in town or anything like that.”

“People attend everything. It's not just football,” he says. “People try to compare it to Friday Night Lights and all the stuff that happened back in the '70s and '80s in Odessa, but it's not like that everywhere."

Collin County residents have the highest median income in the state — it's one of the 25 wealthiest counties in the country. But you won't find the sprawling lawns and century-old homes of Highland Park or River Oaks here. The treasures are more attainable: rows of spacious, neatly plotted ranch-style houses under black roofs of the kind that look identical from the air; an outdoor shopping mall complete with its own lake that boasts a P.F. Chang's and a Cheesecake Factory; an array of parks and hiking trails; a community event center with its own ice rink.

Soon the stadium will be the main attraction, though folks outside of Allen are talking more about it than folks here, who take the expense and size wholly in stride. Many give a wary response like Westerberg’s — and pointedly observe that it won’t even be the largest high school stadium in Texas. That’s because as news spread of its cost, outlets including Sports Illustrated and ESPN ran items on the stadium, stinging a conservative community with unwanted national attention.

“People will tell you it's all about football, because we're big and we've won," says AHS athletic director Steve Williams. "This is not a community that is football-obsessed. When you become successful at something, you immediately become accused of paying too much attention to it, usually from people who lost to you. We're not that way."

Outsiders assume, for instance, that football trumps academics at Allen High and that building a megaschool (with the huge sports recruiting pool it creates) all goes back to football — so the stadium must be a monument to misplaced priorities. But there’s no sign of trouble in the school’s academic performance; it ranks among the best schools in Texas.

Williams emphasizes that the stadium will include facilities for other sports, like locker rooms for the golf team and a place to hold wrestling (which, in his deep drawl, comes out as “wrassling”) matches. From the window in his second-floor office, he’ll be able to see it all or, as he jokes, “the back of a scoreboard.” Right now, the view is of an expanse of tawny, overgrown grass that hints at the farmland Williams said it was when he first arrived in Allen in 1975.

The facility was no impulse buy. Allen Independent School District set that land aside in 1995 specifically for a football stadium, to be built when the district reached full enrollment levels. That time has come. Since 1995, the school has grown more than 200 percent, from a K-12 enrollment of 6,800 students to its current 21,000.

"I think Allen is a unique place, and it's hard for people in other parts of the country to understand its size and scale,” says Allen Independent School District spokesman Tim Carroll, who said he handled around 40 media inquiries in a span of three days when the story blew up. “But they have to understand that Allen has a high school of 5,000 students."

“A lot of teams hate us”

At the same time the school’s planning group chose to reserve the land outside Williams’ office for a stadium, it decided that the district would only have one high school, which is now the third-largest in the state. (The high schools with the four largest enrollments in Texas — Plano and Plano East, in front of Allen with just over 5,000 students, and Plano West, behind it with just under 5,000 — are in Collin County, which is second only to Dallas County as the fastest-growing county in the state.)

The plan for one big school stemmed from a desire to “avoid inequitable distribution of resources, of programs, have a sense of pride in one place, avoid an East/West divide,” says Superintendent Ken Helvey, who has lived in Allen since 2001 and has held the school district's top job since 2006. “You wanted equitable opportunities for every child to engage in a quality education. That was really a big push, and it looked like from the standpoint of the enrollment projections that it could be done."

According to Helvey, AISD is done growing. Its 28 square miles are landlocked on all four sides by Plano, Frisco, McKinney and Lovejoy, allowing the district to plan carefully for growth and infrastructure.

Leica Smith, who owns A-Town Sports, the local spirit store that sells Eagles-themed clothing, and whose two sons played football at Allen, says she was initially against Allen ISD’s decision to have a single high school. She worried about how large it would get. Now she just loves it, because the economies of scale ensure kids don’t get cut out of extracurricular activities.

It’s no secret that the large size, and the money that comes with it, allows the football team to pound opponents into the turf, as it often does. Smith says she regularly hears of families moving to the district in junior high so their kids can play football in high school. She herself moved to Allen in 1994 because she wanted a “small-town experience” for her kids, though she says “that's not really happened” because of the area’s rapid development.

Smith's youngest son, Tracey — who was a defensive lineman on the team that won the 2008 state championship — acknowledged the perception that its football might is connected to Allen’s size and affluence.

"A lot of teams hate us," he says. "I guess, just being Allen, we have a lot more advantages. Some of our facilities are nice, and we only have one school, and a lot of people think we wouldn't be as good if we had to split up schools. We're always doing well each year, so we basically have enemies all over the map."

His mother also shrugs off any suggestion of the new stadium’s extravagance. "That's what it costs to build stuff nowadays,” she says in her no-nonsense, animated way. “I know there's a recession going on, but hey, how many people are going to be put to work on that stadium? And it was voted on — we all wanted it. Maybe they keep their opinions to themselves, but I have not heard anyone come in here and complain about it.”

“People like to win”

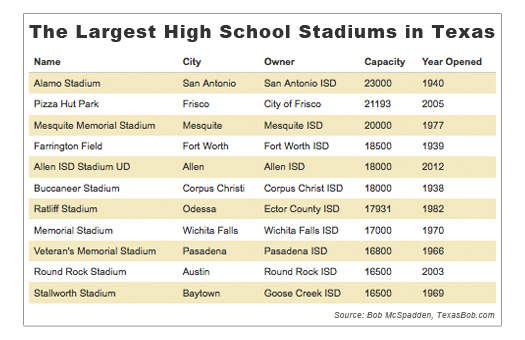

It’s true that the stadium, despite its jaw-dropping cost and size, won’t even be the largest in Texas when it’s completed in 2012. That honor goes to San Antonio’s Alamo Stadium, a Works Progress Administration project finished in 1940 that seats 23,000. After Alamo, two other stadiums hold 20,000 or more: Pizza Hut Park in neighboring Frisco, which was built in 2005 as a joint project between the county, the city, the school district and a private operator at a cost of $80 million; and Mesquite’s Memorial Stadium, built in 1977.

Farrington Field in Forth Worth and Corpus Christi’s Buccaneer Stadium both rival Allen, with capacities of 18,500 and 18,000, respectively. But all those stadiums serve multiple teams, often all the teams in a district. Allen’s is the home of the Eagles, period.

According to Bob McSpadden, who runs the eponymous TexasBob.com, a site that includes a huge repository of stadium stats, one of the “first really big-dollar stadiums” was Odessa’s Ratliff Stadium, which was built in 1982 and has a capacity that hovers just under 18,000.

“Everyone was aghast; it was unbelievable that they would build a stadium like that for a high school," says McSpadden, who came of age there during the 1960s — though he was part of the band, not the football team — and currently works in Houston as an adviser for Shell Oil Company. "It’s still one of the largest stadiums in the state and it's still a very nice stadium to go to, but now it’s old hat." Still, McSpadden says he occasionally makes the nine-hour drive to Odessa to attend games.

Ratliff was built shortly after Odessa’s Permian High School (the subject of Buzz Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights, which was made into a film and is now a television series) had a string of state championships in the 1970s. McSpadden says selling a stadium with a hefty price tag to voters is easier because of the revenue a state championship can bring into a school district through ticket sales.

“There’s always additional monies afterwards. Any player will tell you the best year to play on a team is after a championship, because you get new uniforms and equipment,” he says. “It’s also a pride factor. You can't get around that. People like to win.”

Districts can also push stadiums on the basis that they will eventually pay for themselves through advertisements or naming rights. (Carroll, the Allen ISD spokesman, says the prospect of selling the naming rights to the new stadium has not been discussed.) Districts usually pay for bond initiatives like the one in Allen over a period of 15 to 20 years — with interest — through increases in property taxes.

But because of the condition of Allen’s current stadium, one McSpadden says has “a sorry reputation,” superintendent Helvey says the $60 million price wasn’t hard for voters to swallow.

"The fact that this facility was needed was a question that was settled years ago,” he says. “So it wasn't a hard sell to say, 'Do we really need an 18,000-seat stadium?' Plus, I don't think anybody could have envisioned 600, 700 members in a marching band."

The school currently rents an additional 7,000 seats worth of portable bleachers to house fans on Friday nights, in a stadium built in 1976 to hold 7,000 people. That’s still not enough to accommodate demand for tickets — one parent camped out for two days for a chance to snag some of the rare season tickets that were free at the beginning of this year and still didn’t get them. Others must navigate an elaborate barter system that emerges when people suspect a family might be ready to relinquish theirs. Even though her son will play football at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania this fall, Smith says she’s keeping her tickets in Allen.

"People don't give them up. They just don't. I'm not giving mine up. Even though my son's going off to college, I'm just not. And I've had a parent with an upcoming football player say, 'Hey, are you going to give up your tickets?' And I said 'No, but I'll let you use them every now and then,'” she says, sitting in her office in front of a framed needlepoint on the wall that reads, “Faith … makes things possible, not easy.”

Smith says that after his team won state, the way Tracey was recruited made her realize that “there’s just nothing in the world like football in Texas” — scouts eyed her son she says, like “he's a prize bull over at the stockyards or something.” And when his new teammates at Bucknell saw his state championship ring, "they were just in awe."

"The college kids were just like wow — because it's Texas. It's a Texas 5A championship. It's like the best of the best."

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Morgan.jpg)