GEORGETOWN — John Bradley is a man evolving.

A supremely confident and legendarily tough Texas prosecutor, Bradley says he is learning some of the most important — and humbling — lessons of his 24-year career. It’s a painful process, he says. It is also highly public.

“I have been through a series of events that deeply challenged me,” Bradley, the Williamson County district attorney, said during an extended interview with The Texas Tribune. “I recognized that I could be angry, resentful and react to people, or I could look for the overall purpose and lesson and apply it to not only my own professional life but teach it. And I chose the latter path."

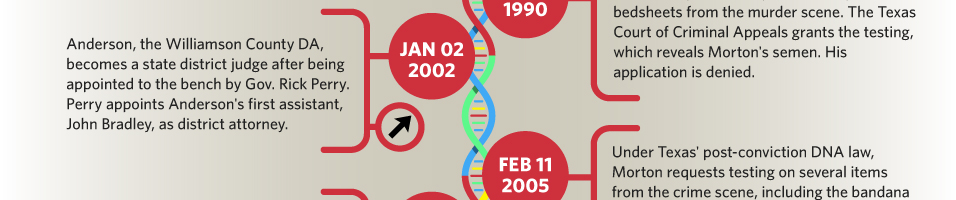

In the last two years, Bradley and his trademark sharp tongue have been at the center of two of the most controversial murder cases in Texas. In 2009, as chairman of the Texas Forensic Science Commission, he and the New York-based Innocence Project battled aggressively over re-examining the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, the Corsicana man executed in 2004 for igniting the 1991 arson blaze that killed his three daughters. For six years, Bradley also fought the Innocence Project’s efforts to exonerate Michael Morton, who was wrongly convicted of murdering his wife under Bradley’s then boss in Williamson County 25 years ago.

Bradley discovered that not only was he wrong all those years about Morton’s guilt, of which he had been so certain, but that there are serious questions about whether his predecessor may have committed the worst kind of prosecutorial misconduct: hiding evidence that ultimately allowed the real murderer to remain free to kill again.

Some of Bradley’s critics are skeptical of his self-professed transformation, and they say it can’t atone for the years that his stubbornness allowed Morton to remain wrongly imprisoned. But some are hopeful that his lesson will lead other prosecutors to acknowledge that science can reveal and help correct flaws in the state’s criminal justice system.

“He is, I think, a reasonably principled guy who is a complete product of a system that is finally giving way to a new day here in Texas and the rest of the country,” said Jeff Blackburn, general counsel for the Innocence Project of Texas.

Bradley grew up as a prosecutor in his hometown of Houston under Harris County District Attorney Johnny Holmes, working there from 1987-1989. With his handlebar mustache waxed into perfect curls above his lip, Holmes was the iconic Texas prosecutor. From 1992 until 2000, while Holmes was in office, Harris County sent 111 defendants to death row, according to a 2010 report by Drake University Law School professor David McCord.

“He was a true Texas lawman,” Bradley said, drinking coffee at a diner across from Georgetown’s historic courthouse. “It was an honor to learn while working in his office.”

The workload was crushing. He worked 70 hours each week in an office where defense lawyers were viewed as hostile enemies. “I always felt like I was swimming among sharks,” he said. “And you had to defend yourself, and you have to be the same predator back.”

Rob Kepple, the executive director of the Texas District and County Attorneys Association, worked with Bradley in Harris County. Under Holmes, he said, they were taught a prosecutor’s first job is to be tough.

“Your citizens expect you to fight crime,” Kepple said. “They expect you to stand up for them. Our job is to be tough, tough but fair.”

When Bradley and his wife Leslie decided to expand their family, he said, they moved to Williamson County, a place that was smaller, but had a reputation for being just as tough on crime.

Williamson County District Attorney Ken Anderson hired Bradley, and he set up office with a card table, a folding chair and an old Mac Classic computer in the courthouse hallway.

“It was a tremendous culture shock,” he said.

It wasn’t just the plain digs. Almost immediately, Bradley said, he realized he couldn’t treat defense lawyers like “sharks” in this small community. “Your professional relationship is an important part of being a lawyer, something I did not develop in Houston that I’m still working on,” he said.

They may have been nicer, but that didn’t mean prosecutors weren’t tough. Juries and judges in Williamson County meted out long sentences.

Through the years, Bradley developed a close relationship with his boss. They co-wrote two law books. Under Anderson, he began working with lawmakers at the Capitol, just a 30-minute drive south of Georgetown. When Gov. Rick Perry appointed Anderson as a state judge in 2002 he also appointed Bradley to take over as district attorney.

Mark Brunner, who is now a criminal defense lawyer in Georgetown, spent two years working in Bradley’s office. He described him as a “hands-on” prosecutor who didn’t allow his assistants much discretion in decision-making about their cases. And he said Bradley did not encourage prosecutors to be friendly with defense lawyers.

“They’re expected to be tough always and hard always,” Brunner said, “and if you deviate off that you better have a damn good reason.”

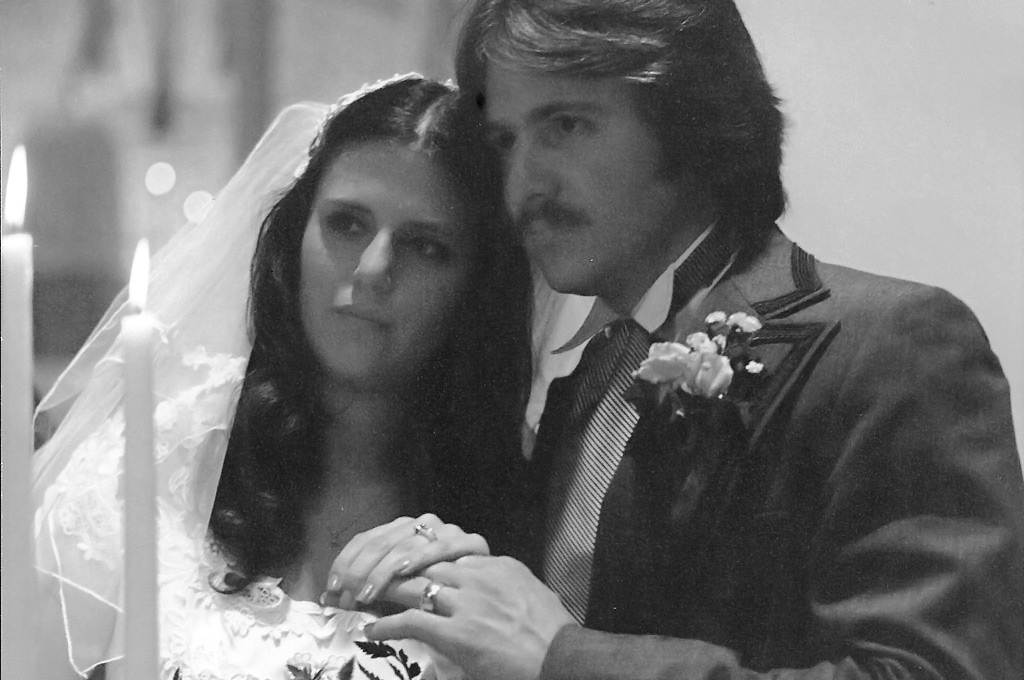

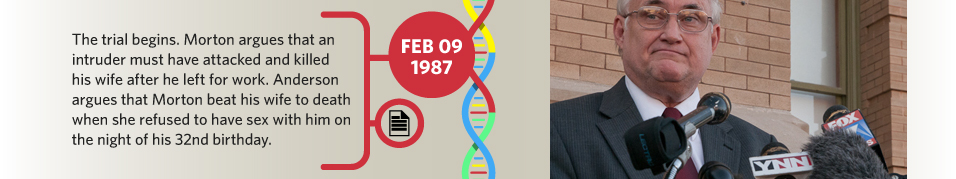

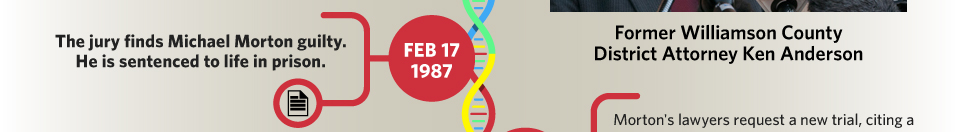

When Bradley arrived in Williamson County in 1989, Michael Morton had already been in prison for two years. Anderson prosecuted Morton for the 1986 murder of Morton’s wife, Christine. He told jurors that Morton brutally beat his wife to death after she refused him sex on the night of his 32nd birthday. The jury sentenced him to life in prison.

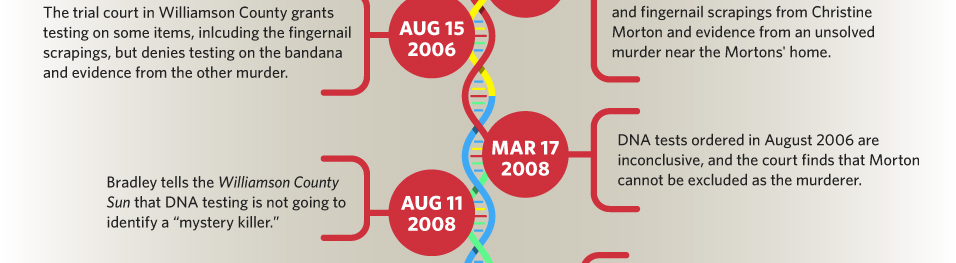

Like many convicted criminals, Morton maintained his innocence, arguing that an intruder must have killed his wife after he left for work in the morning. In 2005, Morton began asking the state to test DNA evidence on a number of items, including a bloody blue bandana found near their home the day after the murder.

Bradley tenaciously fought the requests. In the press, he berated the idea that DNA would lead to some “mystery killer.” And he said Morton’s lawyers were “grasping at straws.”

"Once a prosecutor has a case in which he or someone else has achieved a conviction where a body of people have been convinced beyond reasonable doubt someone is guilty and then sentenced them, the presumption becomes that that is a justified verdict that the prosecutor must defend," Bradley said, explaining his opposition to Morton's requests.

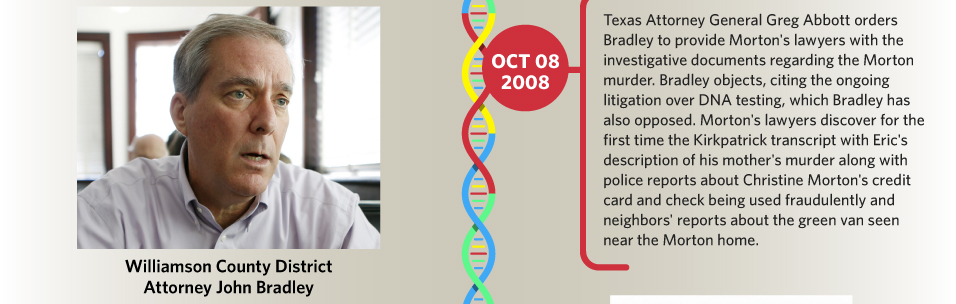

Morton’s lawyers also asked Bradley, through public information requests, for investigative materials in the case. From the time of his conviction, Morton’s lawyers suspected that prosecutors had withheld key evidence that could have caused jurors to doubt his guilt. Bradley fought that request, too, arguing it would interfere with the DNA litigation.

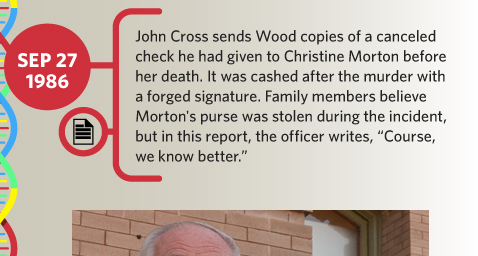

Eventually, Bradley lost that fight and turned over the files. Reports from the sheriff’s department showed that in 1987 investigators had several clues that pointed to someone other than Morton as the killer. There was a transcript in which Morton’s mother-in-law told a sheriff’s deputy that the couple’s 3-year-old son saw a “monster” with a big mustache attack his mother — and the monster wasn’t his father. There were reports that Morton’s credit card had been used and a check had been cashed with her forged signature days after her death. Morton’s lawyers, though, had seen none of that information during his trial.

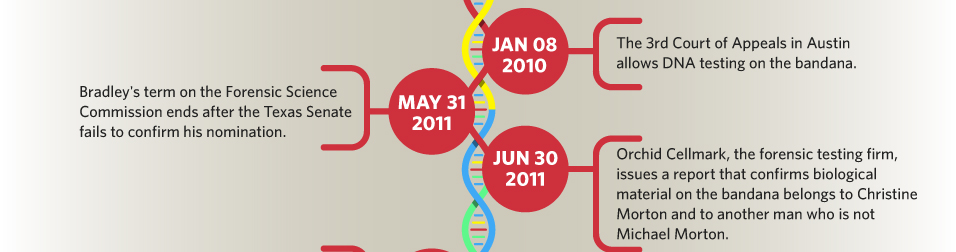

While Houston lawyer John Raley of the law firm Raley & Bowick, and the Innocence Project fought with the prosecutor in court to get the scientific testing done that they believed could exonerate Morton, another but unrelated conflict was unfolding.

The governor appointed Bradley to lead the Texas Forensic Science Commission just as it embarked on a highly controversial investigation of the Willingham case. The Innocence Project had filed a complaint alleging negligence and misconduct in the arson investigation. It also wanted the commission to require the State Fire Marshal’s Office to review other arson cases to determine whether mistakes were made that resulted in wrongful convictions. The commission was set to hear a report from nationally-recognized fire scientist Craig Beyler that raised questions about whether Texas had executed an innocent man.

Bradley abruptly cancelled the meeting, and the pace of the Willingham investigation slowed dramatically. The Innocence Project alleged that Bradley was protecting the governor from potential political fallout during his gubernatorial re-election season. Bradley countered that Barry Scheck, the Innocence Project’s co-founder, and others, were using the commission to attack their real target — the death penalty. Conducting such an investigation, Bradley argued, was outside the commission’s authority.

There were finger-wagging shouting matches. Bradley called Willingham a “guilty monster.” Protesters lined up at commission meetings and carried signs with messages like “John Bradley is a tool … of Rick Perry.”

“It was hostile,” Bradley said last week.

Eventually, lawmakers intervened, and the Texas Senate declined to confirm Bradley’s appointment to remain on the commission. After Bradley left the board, the Texas Attorney General produced an opinion agreeing with him that the panel did not have authority to investigate the Willingham case or others that took place before the commission’s 2005 creation.

“I think ultimately I was proved correct,” he said. Still, the commission finished a report on the Willingham case that includes Bradley's work and has paved the way for an unprecedented review of older arson cases.

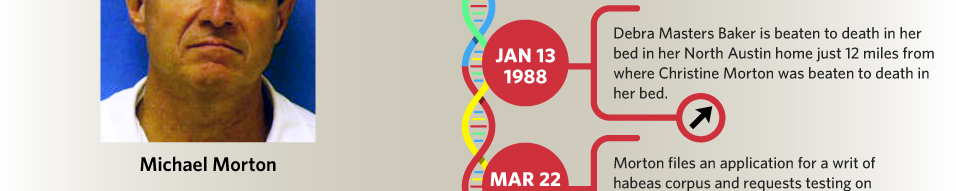

While the Willingham controversy continued in 2010, the Morton case was beginning to unravel. An appeals court ordered the prosecutor’s office to allow DNA testing on the bandana found near the murder scene. In June, the test results revealed that Christine Morton’s blood was mixed with the hair of a man who was not her husband. In August, a national DNA database search matched that DNA to a felon with a record in California.

But it wasn’t just the DNA.

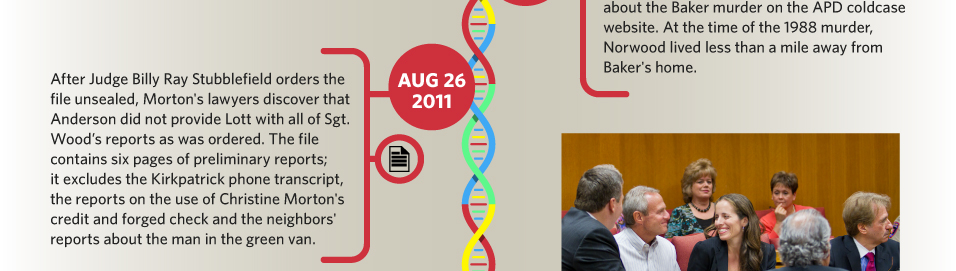

The court in August also ordered the unsealing of a file that was supposed to contain all of the reports from the initial investigation of Morton’s murder. During a dispute in 1987 over evidence, the judge had ordered Anderson, the prosecutor, to provide him all of the investigator’s reports so that he could determine whether there was any information that could help Morton prove his innocence.

When that file was opened two decades later, Bradley and Morton’s lawyers found a paltry six pages of police reports.

Both Bradley and Morton’s lawyers knew that there were many more pages. Despite his order, the judge was not given the transcript that included the Mortons’ son’s description of the murder or the financial transactions that occurred after Morton’s death.

For the defense attorneys, it seemed to confirm their suspicions: the prosecutor’s office had withheld critical information so they could secure a conviction. For Bradley, the development was a shocking revelation that raised serious questions about his former boss and friend.

“I fully expected that that sealed file would contradict some pretty strong accusations,” Bradley said. “It didn’t.”

Then came another, perhaps even bigger bombshell.

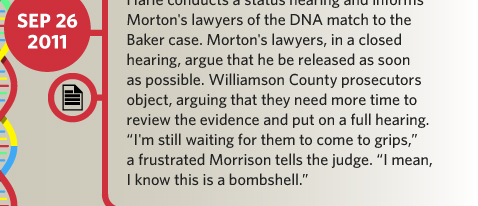

In September, Travis County investigators linked the DNA from the Morton bandana to DNA found on a hair at the scene of the 1988 murder of Debra Masters Baker. The man whose DNA was on those items during the 1980s lived only blocks away from Baker and about 12 miles away from the Morton’s home.

“It’s the kind of thing that happens only in Hollywood movies,” Bradley said. "I am still awed by the combination of circumstances that came together at the right time."

Within days of the DNA match, he came to an unusual agreement with Morton’s lawyers, including Barry Scheck — the attorney he’d engaged in hostilities with during the Willingham inquiry — to release Morton from prison and to allow an investigation of potential wrongdoing by Anderson.

“Who would’ve thought that one of the strangest conclusions in all of this, is I consider Barry Scheck a good friend,” Bradley said.

Because of the continuing investigation, Bradley won’t say whether he believes Anderson knowingly hid exculpatory evidence. But, for now, he said, their personal relationship is gone. “It saddens me, but that’s the facts,” he said.

In his first public comments about the case this week, Anderson acknowledged the outcome in the Morton prosecution was wrong and said he is anguished over the results, both Morton’s wrongful imprisonment and Baker’s death at the hands of the murderer he didn’t catch. He denied any wrongdoing. “In my heart, I know there was no misconduct whatsoever," Anderson said.

Bradley said he regrets that his opposition to DNA testing over the last six years meant more time behind bars for an innocent man. He also regrets sending letters to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles urging them to keep Morton locked away.

Had he known then what he knows now about the Innocence Project and Scheck, he said he might have handled the Willingham case differently, too.

This experience has taught him to be more open-minded, to try to see cases from both sides, he said. Bradley emphasized that his office is more open than his predecessor's was. And in the future, when defense lawyers bring him cases to review, Bradley said, he will have a new perspective.

“If I had to come up with a slogan," Bradley said, "I don't know that I would use it, but essentially the slogan would be 'We are more than tough on crime.'"

Some of his critics, though, see Bradley’s contrition as too little, too late. And they note that he is facing re-election next year. They want more than words.

“The jury is still out on whether those words will manifest themselves into real actions to help fix what is clearly a broken justice system,” said state Sen. Rodney Ellis, D-Houston, chairman of the Innocence Project.

Scott Henson, who writes the well-regarded criminal justice blog Grits for Breakfast, said Bradley could demonstrate his changed perspective by joining with innocence advocates to promote reforms to the Texas justice system. “He’s got a long record,” Henson said. “And it will take more than a few words of humility to get everyone to believe that he’s had some road to Damascus moment.”

Williamson County District Attorney John Bradley sat down for coffee and breakfast with the Tribune at the Monument Café across the street from the Williamson County Courthouse in Georgetown to talk about his career and how his prosecutorial philosophy has changed through his involvement in the Cameron Todd Willingham and Michael Morton cases.

Below is a condensed transcript of the Tribune’s extended interview Bradley.

JB: I’ve thought about the probabilities of that, of being in a place where I’m on the edge of the development of forensic science as the result of a governor asking me to be there and quickly on the heels of that getting yet another extraordinary lesson, not so much in forensic science, but in really the other developing story about criminal justice, which is how do prosecutors deal with challenges to cases which they had very strong assumptions of guilt on. And both of those experiences have expanded my view of the prosecutors view in a modern world. It would be very easy I think for me to get upset, bitter, and just react to all of that stuff but I’ve never really approached things that way. To me there’s always a lesson there, and it may be a painful lesson, but there’s a lesson. And I’m going to be here, I’m going to continue doing this, I love doing it, and in both of those instances, they’re very different lessons, but they’re both very productive and I apply them daily in how I run my office and how I teach nationally on these issues. So they’re powerful. And who would’ve thought that one of the strangest conclusions in all of this, is I consider Barry Scheck a good friend. He and I have worked together much better on this Morton case than we did on the Willingham case, but I think largely because of the evolution of our relationship.

TT: That is kind of huge.

JB: It is huge. You know, at some point I began to realize that these were national and maybe even international subjects that are being discussed, but they are also very local because in both instances they involve individuals in small communities that had to handle the reaction of the world to what happened in their communities, whether it was in Corsicana or in Georgetown.

TT: That’s kind of a weird place to be I imagine, having such scrutiny in your own small community.

JB: In the Willingham case, I could depersonalize it more. I didn’t prosecute Willingham. I wasn’t even a prosecutor when that case took place, so I think I had some more distance from it. But, at the same time, I think it got personalized for me because I became the imagine for resistance when frankly there was something a lot more complex going on that wasn’t being reported. In the Morton case, although I didn’t prosecute that case as well, I wasn’t even a prosecutor at that time, it was in my community, it was prosecuted by an individual who I had worked for, and who is currently a sitting judge. So, I had to make sure that I kept those personal issues separated from how we resolved the case.

TT: How do you do that? You worked for Anderson for a long time, and seem to have a pretty close relationship.

JB: I ultimately had to decide for myself whether I could objectively develop and cooperate in the collection of whatever information existed. And I had no problem in my mind letting facts develop. Facts don’t change. They exist in the record; they exist in people’s memories. How people want to interpret those facts and apply them was not something that I was going to do. So I reminded myself to keep that separate. What all of this means in the end of it is going to be decided by someone else. What happened, I can help collect.

And I think that Barry Scheck and I ultimately reached a very unique written agreement whereby we would have depositions, brief him on what we knew and allow all of that to be collected in a report and presented. I’m very comfortable that we did that fairly and it’ll be at least good, strong factual information for everyone to look at. And I think if you talk to him he would repeat that. I think he would say that he felt like I was open and honest and fair with him. That’s about all I can aim for.

TT: Was he fair with you as well?

JB: You know, to my utter shock and surprise, I find that I can say without hesitation that he was a gentleman and utterly transparent and honest in how we worked on this.

TT: Talk about your background, where you went to school and how you became a prosecutor.

JB: I grew up in Houston and attending Strake Jesuit was a formative experience. They, at that time and still have Jesuit priests who teach and teach the Jesuit approach to life, where you're among a community of men, but at the same time they are also every single day making you think very critically.

I was in high school debate for four years — totally geeked out on that. And ran my mouth in front of people endlessly in tournaments, but it was a great education. I still send them money to this day because I can see from this point of view how valuable it was.

When I finished there, because I had attended a Catholic high school, when I applied to the University of St. Thomas, which is a small liberal arts school there in Houston, I received a full four-year scholarship. So that’s where I was going. And I majored in English. I love reading. I love literature. And I was completely convinced that I was going to be a novelist, and I may still be. I acted in plays, wrote essays. I was the editor of the newspaper for one year. I wrote outrageous editorials like we all do at that age. And had a very, very good college experience.

I met my wife there. She started there my junior year. She came from New Orleans. She’s a Cajun red head. She introduced me to Mardi Gras, Jazz Fest, gumbo. And once I finished college, I actually applied for and was accepted at graduate school to get a master’s in creative writing at Indiana University, I think. And at the last minute I didn’t do it.

...

I applied to law school. I was accepted at Loyola there in New Orleans and at the University of Houston in Houston. And when I looked at the cost of law school in Houston versus the cost of Loyola, we went back to Houston and I started law school for three years.

My wife deferred finishing her education and she went to work. Actually, it was in the middle of the recession. She had three different jobs, she paid for me to go to law school. We came out with no debt. But oh my gosh, were we poor. We were living in a garage apartment doing babysitting for the people who owned the house in the front.

I hated law school, it was to me the most punitive experience that I’ve ever been through, but you’ve got to get that law degree to practice law. And the one thing that I discovered was that I love criminal law. From the moment I took my first criminal law class, I knew that’s why I was there.

TT: What was it about criminal law that struck your fancy?

JB: It was very simply the fascinating stories. Anyone involved in criminal law, sees, hears and tells fascinating stories every single day. Nobody ever went home and did a fascinating story about the deposition they took that day in a civil case. But at parties and at dinners everybody wants to hear about what crime occurred and why they did it. And I like storytelling so that was a good part of it. And while I was in law school, I interned at the Harris County District Attorney (Johnny Holmes)’s office.

...

Johnny Holmes is a legend in Texas. He had the handlebar mustache that was waxed into a curl. He had worked his way up through that DA’s office. He started as an investigator and went all the way to the top as the district attorney. And he was a true Texas lawman. When he spoke, people listened. It was an honor to learn while working in his office.

So once I interned there I knew that not only did I love criminal law, but I had to be a prosecutor.

When I finished law school, Leslie and I decided to move to Austin first and I worked as a briefing attorney for one of the judges on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals – Charles Campbell. ...

He promoted me to his research assistant, and I thought about staying there but I still wanted to prosecute. So after two years, I applied for and was accepted to the district attorney’s office back in Houston and went back to work for Johnny Holmes.

I was a prosecutor there for a little under three years. In the less than three years I was there, I think I compressed about 10 years of experience. The caseload in Houston, if you’ve ever visited there, is overwhelming. There’s an endless stream of cases and particularly people at the bottom of the food chain get the bigger caseload. And so I worked 60, 70 hours a week. I found that I was working Saturdays and Sundays. I loved it but after about two years, I found that I was disintegrating.

My wife and I had decided to start having children. I was never home. I loved the work side, but I was burning out so we sat down and talked about what to do about that. She was pregnant with our first child, and by the time he was born, I realized I had no time to spend with him.

...

Time after time people would recommend to me that I go to Williamson County. It wasn’t on my radar. I didn’t know about Williamson County, so I applied and got the job. We moved to Williamson County, bought a house near here — old house, almost 100 years old — and spent about 20 years fixing it up, I love it.

TT: That’s got to be a big shock coming from Houston and growing up there.

JB: It was a tremendous culture shock. My office initially was in the original old courthouse here on the square. They were building this new courthouse behind it — I’d be glad to go show it to you — but they hadn’t finished it. My boss actually had no room for me, and he literally put at a card table in the hallway, gave me a folding chair and I sat at my little Mac Classic that I had bought in law school.

...

Well, what I immediately hit, and frankly this is the beginning of an education that still hasn’t finished. I came here was with the prosecution philosophy that I had accumulated in Houston. I always felt like I was swimming among sharks. Defense attorneys were sharks, and you had to defend yourself, and you have to be the same predator back.

And one of the first lessons I learned was that does not work in Williamson County, where there was much more of a relationship with the lawyers. There was a lot more trust. I had to begin to alter my personality. There will be a lot of debate over the success of that, but believe it or not, I have evolved a lot and continue to work on that side of it, and it’s something that I teach constantly in my own office. Your professional relationship is an important part of being a lawyer, something I did not develop in Houston that I’m still working on.

But the next most significant event for me was the birth of our next two children.

...

I need 23 more home births and I am a certified midwife in Texas. So whenever I tell that story, I ask anybody in the audience if they have a birth coming cause I only need 23 more. So far, no takers though.

TT: Talk about working in the DA’s office for Judge Ken Anderson.

JB: Yes, Ken was the district attorney at the time. He certainly had a reputation of his own in the state. I quickly began to hear and see that Williamson County even at that time was a place, to use a typical phrase, that was tough on crime. Which I think was accurate. I think there’s a lot more nuance to that than gets reported, but juries and judges definitely in cases involving violence and repeat offenders, tended to sentence on the outer edges, to put it mildly.

TT: What sort of philosophy do you think you learned from the way he ran the office and handled cases?

JB: That’s a really good but hard question, because modern prosecution in a modern office like the one that I have now is strikingly different from what I encountered 20-25 years ago. There are so many more tools today: computers, how files are developed, the kinds of forensic evidence that are available, the kinds of training that prosecutors receive, the expectations of the professional world now versus than back then – so there’s frankly very little that is similar to how my current office runs to what I experienced then in terms of the structure and the approaches.

I sometimes think I need to write an essay about the difference between an office 25 years ago and a modern prosecutors office, dealing cases like the Morton cases. I think one of the things I’m going to spend a lot of time talking to people about is the Morton case clearly had some issues.

Not only was the outcome wrong, but as I think Barry Scheck and I will report at some point, the manner in which things were developed 25 years ago may have contributed to those issues. Very few of those types of structures still exist, and I need to let people know that.

In fact I did write an essay that I distributed in the local papers about discovery. For example, in Houston where I started, discovery was essentially an open file. We’d hand our file out to the defense attorney, and they could read it. When I moved here, I encountered a much more restricted discovery policy. Things were held a lot more closely. The style in which information was conveyed was much more controlled by the prosecutor.

I have evolved very far away from that. We have an open file policy in my modern office. If a person’s going to trial, the most frequent complaint we get from the defense attorneys is we’re giving them too much stuff, because we just unload it and show it to them. ...

TT: In the court filing where the Innocence Project asked you to recuse yourself, they seemed to be under the impression that you knew that there was information that hadn’t been turned over in the Michael Morton case.

JB: Yes, I think that clearly was their initial impression. I think that they would agree that I corrected that misimpression. I have very honestly and carefully shown them that we learned about the concerns they had literally at the same time they did when that sealed file was unsealed.

TT: What was your reaction to that?

JB: Initially, shock and then sadness, because I fully expected that that sealed file would contradict some pretty strong accusations. And based upon what I knew about the record from reading the deal, it certainly looked like that was going to have all of the material that they would have wanted to look at. It didn’t and that raised an enormous new question that Barry and I have been working to address, and I think that they would agree. I had a long conversation with Barry this week and he reassured me on all of that, that he is comfortable that the modern office, the current office, was not involved in anything and has been cooperative in helping them figure out what happened.

TT: How did that discovery affect your relationship with or what you thought about your old boss, Judge Anderson?

JB: Well for now there is no relationship. It has to be separated, because under the circumstances as they currently exist I’m a potential witness. And just as I would expect any witness in one of my cases to remain neutral and available without outside influence, that’s the approach I have to take.

Professionally I understand it. Personally, you know it saddens me, but that’s the facts.

I don’t want to infer or suggest in any of this any particular conclusion about what all this information is going to mean or result in. That’s for someone else when they hear those facts to decide. I am not in a position to decide those things anymore than any witness would be.

I hope that whatever form all these things are resolved in will be open and fair.

TT: During his deposition, former assistant district attorney Mike Davis talked about a recent conversation between you and Judge Anderson in which voices were raised inside his office. Can you talk about what happened in there?

JB: I would love to but since I am a potential witness in all this and those conversations like that one may potentially come up in other proceedings, I’m going to have to defer until those proceedings take place when I potentially become a witness.

I don’t want anybody to read anything in particular into it at this point.

TT: How do you feel now about resisting the DNA testing and resisting giving up the documents the Innocence Project asked for in their public information request?

JB: There are two answers to that. The short answer is in hindsight I regret any delays that I contributed to the exoneration of Michael Morton. He is an innocent man and deserves whatever information the state can provide him.

The long answer is a little more complicated and most of the time doesn’t get discussed or reported. Prosecutors have a very complex set of standards that they have to balance when those kinds of issues are raised.

The defense attorney in many ways has a much simpler standard. It’s his job zealously represent a single client and take any reasonable position to advance that. So he can be zealous and even when he has doubts go forward and understand that the system is going to filter that stuff out.

The prosecutor does not have that same standard. The prosecutor has a broader standard of seeking justice. Once a prosecutor has a case in which he or someone else has achieved a conviction, where a body of people have been convinced beyond reasonable doubt that someone is guilty and then sentenced them, the presumption becomes that that is a justified verdict that the prosecutor must defend.

My initial entry into the Morton case has to be one in which I start from the assumption it is a justifiable, defensible verdict. I get claims of innocence hundreds of times every year. I get letters, I get phone calls, I get pleadings, and in each one those cases, 99.9999 percent of the time it is a false claim. I have litigated cases in which I have proven that the defendant made up evidence or that a witness was threatened and that’s why they gave up an affidavit.

So it’s probably not surprising that I would come to that case with first the assumption the verdict is appropriate and skepticism about claim of innocence.

What I have really learned, and I think this is a tremendous lesson through the Morton case, is that even though I have a duty to protect that verdict, there is a part of me that — in what seems like irreconcilable conflict — also has to maintain an open mind.

I think it took me longer in this case to access that part of my approach than I will in the next case.

I will tell you that I would congratulate Barry Scheck on his patience and his willingness to engage in some meaningful dialog with me to help me get there.

TT: How did he help you get there?

JB: Well we had a lot of conversations. But essentially the single most motivating part of that was that I found him to be a reasonable rational person who was working on the facts and not an agenda.

Now, ultimately the DNA evidence spoke louder than anything else.

TT: What if there hadn’t been that DNA match to the Baker case, the cold murder case in Austin?

JB: It’s weird, because the Baker case on its face has nothing to do with this. But that was the bolt of lightning for me that erased all doubts whatsoever.

While DNA will tell you something biologically, the inferences that you draw from it are not automatic and they’re not always automatic. The fact that someone’s biological material is on a piece of cloth doesn’t necessarily tell you anything, particularly if it was collected 25 years ago and you have some information that causes you some concern that it could have been contaminated or that the chain of custody was messed up. Lawyers can always come up with alternative explanations.

But it’s pretty hard to come up with an alternative explanation for biological material that is at two separate crime scenes that are very similar and is focused on one person. That’s the kind of thing your eyebrows go BING! It’s the kind of thing that happens only in Hollywood movies. That’s the money moment in the movie.

So yes, I think that was critical. And again, the Innocence Project gets credit for identifying that cold case, going to the Travis County DA’s office and asking for them to look at it.

...

The persons’ DNA that connected in both those cases was not put into a national database until 2010. So I have to wonder by what incredible series of combined circumstances that comes up at the same time that these cases hit.

If you had done that DNA testing back in 1986, 1987, let’s say we had DNA testing, what would you have? You would have a piece of cloth with some unknown DNA. And in all likelihood any good prosecutor could provide an alternate explanation for that. Any jury could reasonably say it’s irrelevant and could still convict. It isn’t until you connect it to a person that you then connect to the case that it becomes valuable.

I am still awed by the combination of circumstances that came together at the right time. ...

We were talking about evolution of my mind and it’s openness. You can imagine then how it has changed my view of what DNA evidence can do when you’re just looking at it for investigative reasons. Not as a solution, but let’s see where it goes, and I think that this case, I hope, teaches prosecutors to be more open to what those circumstances can mean. ...

TT: How has all of this affected what you think about the Willingham case and the Forensic Science Commission and looking at older cases?

JB: I have never had a problem looking at older cases. If you look at the specific work that I did at the Forensic Science Commission, any resistance that I had to looking at older cases was based upon my reading of the statute.

One of the biggest principles I live by is following the rule of law. From the very earliest stages of my appointment to the Forensic Science Commission, I recognized that there was going to be huge public conflict between what law said the commission should be doing and what some people wanted the commission to do. I recognized that was going to result in a big public debate, and to some extent I was going to become the poster boy for their agenda. I knew that before I agreed to do it. I knew that it was going to be controversial, but I so strongly believe that someone has to speak to the rule of law that I agreed to do it. I think ultimately I was proved correct as to what the law said and what it meant. The attorney general opinion is strikingly similar to the legal arguments I made from the beginning.

What made that complicated was the separate debate that was going on about guilt or innocence of someone who was executed.

The mistake that I made, in hindsight, was allowing myself to be drawn into discussion of guilt-innocence, rather than remaining focused on just the forensic science. You kind of had to be there and feel the pressure and the tremendous newness of the job and the topic. I don’t know that I could have done it any better than I did.

Obviously, you learn a lot of lessons. If you did it over, you would do it differently. I don’t have any regrets. I enjoy every experience that I have as long as it doesn’t kill me.

I knew I was going to be OK one of the days when I was walking into one of the commission meetings and they had the usual protesters out front and one of the people was holding a poster. All I could see from a distance as I was walking up was it said, ‘John Bradley is a tool.’ I thought, ‘Wow that’s not very creative.’ Then I walked up and in small letters at the bottom it said ‘of Rick Perry.’

I laughed the hardest. I seriously wanted to take out my iPhone and ask her if I could take a picture, because it just condensed the political minefield that I had walked into, but I appreciated the humor.

I didn’t take the picture then but I eventually found a photograph of it, and I’ve kept it. It reminds me that you just have to have a sense of humor about what’s going on and just do your job.

At some point you have to distance yourself when people have made you a symbol of something that they want and it’s an issue of great concern to them.

...

We wrote a report on Willingham, a report that I think most people are pretty impressed with. I was involved in creating every single word of that report. It was excruciating, but that report has now been adopted and finished. And the legal issue that I held from the beginning that the commission did not have the authority to decide negligence or misconduct in older cases was ultimately proven to be accurate.

It was adopted and it is discussed in that report. The rest of the report has some fantastic information about the evolution of arson science. I embrace and support every bit of it. I have never had a bit of education on that particular forensic science. I feel like I went to college on that, and it was great.

But all of that gets lost in the shuffle of this other political battle that was going on.

TT: You’ve seen the documentary film Incendiary, right?

JB: I have not. I’m going to give it some time. It’s on my Netflix list. I’ve talked to a lot people who have seen it.

TT: The way that movie portrays the relationship between you and the Innocence Project is very hostile.

JB: It was hostile. I can give you that. It was hostile. It’s pointless now to try to figure out who’s to blame for that. It was hostile, and I think it was escalated from my point of view, because I perceived that the Innocence Project was pushing a political agenda more than forensic science.

I am quite prepared to concede that I might well have misjudged all of that. If I did it all over again, I would look at Barry Scheck through different eyes. Isn’t it fascinating that despite our conflicts on that case, in a case that is equally or maybe even more controversial, we came to terms and dealt with each other more professionally?

TT: What do you think is the difference?

JB: I don’t know. I think it probably requires someone with more objectivity than I have to answer that question. I’m glad it happened. I think it was very productive and successful, and I’m confident it will result in a longer-term professional relationship. I’ve told him that I would love to do some joint things with him publicly at national conferences or legislatively and I’m confident that we will.

It doest mean we’ll always agree. Listen, we’ve got a lot of distance between us on certain legal issues, but there’s a lot of common ground.

TT: Where does this leave you in terms reviewing other cases in Williamson County to determine whether there might be other innocent people convicted?

JB: I have always conducted my office so that we address those kinds of issues at the front ends of cases. We have a very rigid screening process before any case ever makes it to a prosecutable felony.

...

In a modern office, the cases that end up going to trial, in our world we call them whales in a barrel. These are cases in which guilt is never really the issue it’s about punishment. If you look at the list of cases that have gone to trial in the last 10 years in Williamson County they’re about punishment.

The Morton case was about guilt.

I am much more self-aware of cases if they come to our office through that process and we get to trial if we still have concerns about proving guilt. That’s a case that’s going to get an extraordinary amount of attention.

...

TT: What about convictions under your predecessor, Judge Anderson? What are you going to do about those?

JB: People will bring us issues, and where they think that they should be re-examined, we’ll do it. And I will have a much better perspective on what that means.

That’s a very cutting edge developing part of our understanding of the duty to seek justice.

Frankly, most prosecutors finish a case, they plead it or they try it, that file goes in a drawer and you forget it. You pretty much have to because of the volume. You cannot accumulate hundreds of thousands of cases in your head and constantly rethink them. So to some extent the defense attorneys have an obligation on their side. Whoever represented that person, if there are forensic developments that they think could be valued in reinvestigating the case, then I think they have a duty to consider that and pursue it and at least bring it to our attention. I don’t know what happened 25 years ago. The ink on my license wasn’t dry.

I know that some offices create what they call a conviction integrity unit and in a very large office I suppose that makes sense. My conviction integrity unit is every single person that works in my office.

...

It goes back to that complexity of a prosecutor’s duty. I’m supposed to come to a conclusion and pursue it, but I’m also supposed to keep an open mind, and frankly probably keep that open mind endlessly. It doesn’t mean you believe everything you hear and accept it and act on it, but you consider it. That is a balance that I think takes a professional lifetime to achieve, and I’d say I’m about halfway through it.

My concern is that we will not maintain an environment where prosecutors are given the freedom to evolve and learn. If they are not given an environment where they can learn from their mistakes then you are going to be left with robots and bad prosecutors. Because there is no perfect prosecutor particularly from the beginning and there is no prosecutor who has gone thru his career without learning from his mistakes.

And I’m concerned that there is something of a culture to punish the prosecutor for every single mistake and remove him from an environment where he can learn.

TT: How do you reach that balance of holding them accountable?

JB: That is a public debate that I think is going on right now and took place this week before the U.S. Supreme Court. And I think you achieve it by dividing mistakes into two types: deliberate and purposeful versus inadvertent.

A deliberate suppression of exculpatory information is unacceptable in any system. The accidental failure to convey useful information is going to occasionally happen. We can correct those.

The first one, there’s no system in the world that prevents that. Those are people who have ignored the rules deliberately.

TT: Which type of happened in the Morton case?

JB: I don’t think I’m in a position to address that. I’m a witness. Other people and other processes will evaluate the info and come to a conclusion. I’m confident that my office acted correctly, and I think the Innocence Project agrees.

TT: In Judge Anderson’s book, Crime in Texas, Your Complete Guide to the Criminal Justice System, he discusses a tradition he started of writing letters objecting to the release of a list of “100 worst” criminals from the county. You continued that tradition. Did you write letters objecting to the release of Michael Morton?

JB: I did, I did. Again, it goes back to my assumption that the judgment was accurate. I had no information at that time to contradict it. And I was obligated to represent the interest of the community and the victim. Unfortunately, they were, in hindsight, inaccurate.

TT: Have you talked to Michael Morton?

JB: I have made the offer. And I think in the right time and the right place when he wishes to I’ll be glad to do that. But I don’t want to force myself on him. If I were him, I would need some time.

TT: It sounds like this whole experience has been an epiphany for you.

JB: An epiphany would be faster than what I have been through. I would say I have been through a series of events that deeply challenged me to evolve as a prosecutor. And I early on recognized that I could be angry, resentful and react to people, or I could look for the overall purpose and lesson and apply it to not only my own professional life but teach it. And I chose the latter path.

TT: Is the primary lesson open-mindedness?

JB: Open-mindedness is kind of wishy-washy. I think the ultimate lesson is to spend more time trying to see the case from the other person’s point of view and not demonize that individual or their argument.

TT: Where does that leave you politically? You have an election coming up.

JB: I’m up for re-election. I’m comfortable that the people of Williamson County understand the context of what has happened. And they recognize that I run a modern professional office that mirrors the political philosophy that they want in criminal prosecution, I have a job to communicate that to them and I’ll do it.

It’s certainly more complex than your average slogan. But this is a very good community for being able to explain that sort of thing.

...

I’ve been thinking about it, if had to come up with a slogan, I don’t know that I would use it, but essentially the slogan would be “We are more than tough on crime.”