Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

Julieta Crispín Castro arrived early for her first day of summer camp, ready to prepare for the state’s standardized test, when the 13-year-old learned that one of her favorite people at Dobie Middle School would not be around next fall.

“I’m not qualified to come back,” English language arts teacher Tatiana Brown-Gomez told Crispín, borrowing language the Austin school district used to explain why she was laid off as part of a sweeping staff shakeup.

Crispín’s face deflated.

“What? That doesn't make any sense,” she said.

The Austin Independent School District fired Brown-Gomez, a handful of other teachers and the principal after Texas gave Dobie two consecutive F ratings under its accountability system, a state tool largely based on scores from STAAR, the state’s standardized test.

Five Fs at a single campus is all it takes for the state to oust democratically elected school trustees and take over an entire district, like the Texas Education Agency did with the Houston school district.

For months, an initial threat to close Dobie and the staffing changes that followed, all to avoid a state takeover, have roiled the Rundberg neighborhood Dobie anchors in northeast Austin. Parents and advocates say the school is the heartbeat of a community made up of working-class immigrants and refugees.

“The school has been there for 50 years. It’s a part of the community,” said Irma Castanon, who runs a Girl Scout troop on campus for Dobie students, many of whom are her daughter’s friends. “That's where all our kids go to school.”

Dobie's uncertain fate underscores a core issue brewing across the state: What happens when the state’s metrics used to measure success and failure in education are fundamentally at odds with how a community views their schools? The question comes as Gov. Greg Abbott has called state legislators back to the Texas Capitol with marching orders to eliminate STAAR and revisit how testing shapes the state’s school accountability system. While the test is controversial throughout the state, it’s not yet clear what may replace it.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

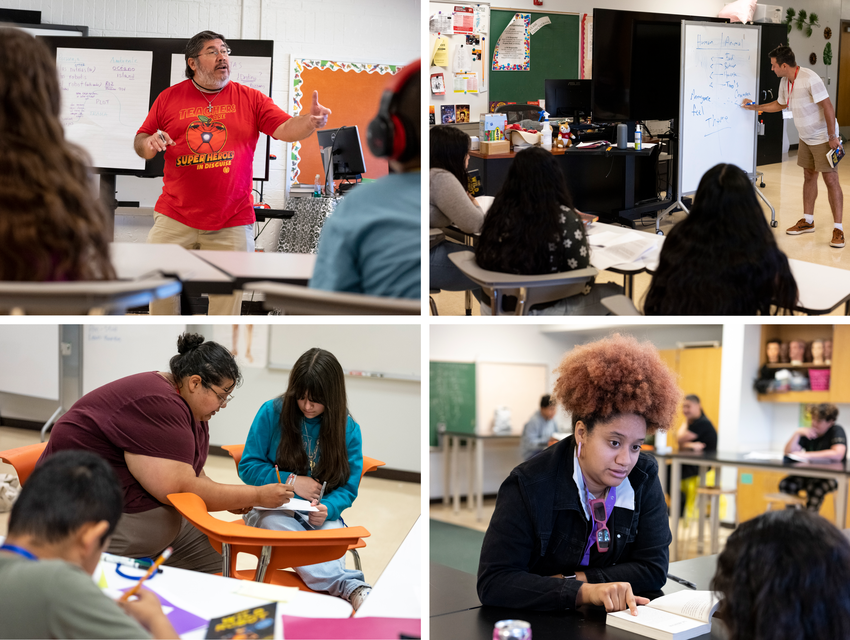

For students at Dobie, the standardized test, an hours-long exam in English, can feel like a language obstacle course. About three in four students are English language learners, many of whom recently arrived in the country.

About 40 middle school campuses across the state serve a similar share of economically disadvantaged students, bilingual students and special education students, just like Dobie does. Of those 41 campuses, five got an A in 2023, 11 got a B, four earned a C, 10 earned a D and 11 — including Dobie — earned an F, according to an analysis from the Texas Education Agency.

“The accountability system gives all campuses the ability to earn high scores no matter where students begin,” a TEA spokesperson said. “The district has failed to offer an effective education for the students of Dobie Middle School for years.”

Families at Dobie don’t want the state to wade into the district’s affairs because of a test they believe is stacked against them. They say the school is serving their children well. It’s a place where their kids can fit in if their English isn’t perfect, where staff understand the challenges that come with settling into a new country.

Students and their families have been fighting all year to keep the school intact, lining up at board meetings with public comment and staging walkouts. After months of hearing their pleas, Austin ISD Superintendent Matias Segura faced Dobie parents in the school’s cafeteria in May. He could buy the school some time, he said.

Dobie would get a restart, Segura explained. The school would stay open under local control, but it would come with a leadership shakeup that would see the principal and many teachers fired.

“The students stay here. The school stays in the community," Segura told them. "We focus on areas of improvement, and we protect the things which we value."

But Dobie’s students will still need to get their STAAR scores up if they want their school to stay.

A Rundberg fight

The Rundberg neighborhood took shape in the early 1970s, built on former farmland with the promise of Little League games and graduations. But those promises have long been threatened by chronic disinvestment. Rundberg has one of the highest rates of 911 calls in the city. Dobie itself has had a history of understaffing, characterized by long leadership vacancies and teacher departures in the middle of the school year, about a dozen community members told The Texas Tribune.

When Dobie got another failing grade earlier this year, district leaders said they were weighing closing the campus. All spring, the Rundberg neighborhood fought back.

At an Austin ISD board of trustees meeting in April, parents held big neon signs that read: “Dobie por siempre y para siempre” (“Dobie forever and ever” in Spanish) and “My future, my school, my choice.” The students staged their own walkout two weeks later, filling Dobie’s front lawn. This was the campus they wanted to come back to in the fall.

Residents like Castanon see the state’s performance demands and the district’s threats to reshape the middle school as outside forces seeking to strip what the mostly Latino community has worked to build.

“The Title I schools are always the ones that have been attacked, and those are the schools filled with brown kids,” Castanon said, referring to public schools that primarily serve low income families and receive federal funding to serve them. “The system, the way they do it, is really unfair.”

At that May meeting at the school, Segura, the superintendent, warned that if test scores don’t improve come December, the district might still need to bring in a charter school to take over operations. Austin ISD did not respond to a request for comment about how that decision was made.

“We would not have instructional control. They would not be AISD employees," Segura said of the potential shift. "And it is something we don't want to do, but it is an option available to us.”

Students will not be bused out to a different school for the upcoming school year, but they are feeling the district’s attempts to avoid outside intervention. Students like Crispín say they need teachers they’ve built deep bonds with, like Brown-Gomez.

“Students are panicking because there’s memories in there,” Crispín said. “I’m just worried about the education [with] the teachers being replaced out of nowhere.”

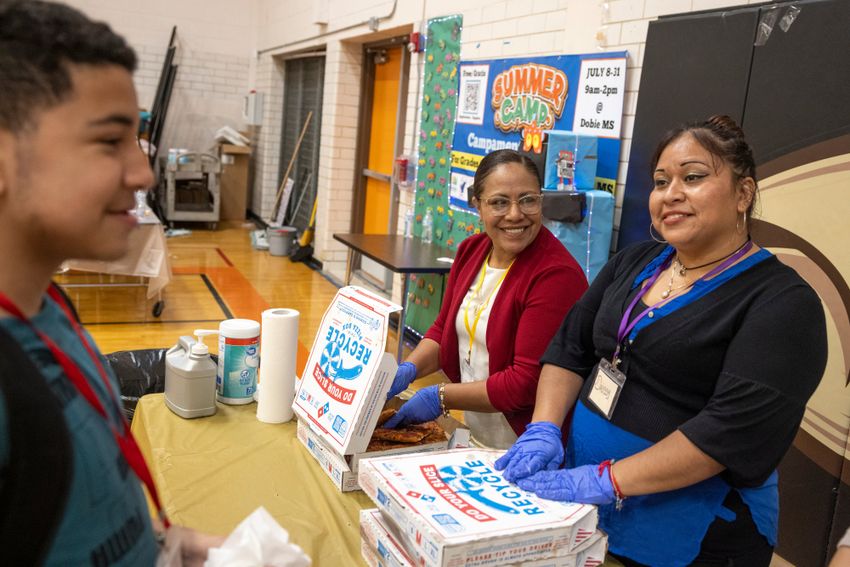

Rundberg parents and a local community group, Austin Voices for Education and Youth, are now running the summer STAAR camp in hopes the students will make enough gains on the test to keep their school doors open and stop a charter school from taking over.

Even though Brown-Gomez won’t be at Dobie anymore, she is volunteering at the summer camp to help students with the test.

“It hurts so much to be here with them right now,” she said. “But I have to do it. This is my last chance.”

An imperfect measuring stick

To the state, STAAR results are a key metric to gauge how well schools and teachers are educating their students. The test is a way to assess how each student is matching up to state learning standards and make sure they are on track for success in life after school.

For more than a decade, Texas students have sat for hours at the end of the school year to take the test. The pressure that puts on students has been widely criticized by families, educators and state lawmakers — and those stakes can feel even higher for English learners and students with disabilities.

Yessyka Velasquez, a Dobie parent, said the test is challenging for her 12-year-old son, who has dyslexia. Besides serving a large population of children from immigrant and refugee families, Dobie also serves an outsized share of students with special education needs compared to the rest of the district and the state.

“He gets anxious. He gets stressed,” Velasquez said. “Sometimes he doesn’t even want to go to school on those days. But it’s mandatory.”

In 2023, nearly 16% of Dobie students met grade-level reading standards, compared to 52% across the state. The difference was starker for math: just 5% of students at Dobie met standards, compared to 43% across the state.

Allen Weeks has fought to keep campuses open at Austin Voices for Youth and Education School. He said the STAAR test and state school accountability system is not set up to meet the needs of immigrant and refugee communities in urban areas, especially those with language barriers. While English learners can take STAAR in Spanish through elementary school, they have to take the exam in English once they get to middle school.

At Dobie, a handful of immigrant and refugee students never went to school in their home country. They started school at the Rundberg campus not knowing how to read or and write, said Sayra Castro, the former president of Dobie’s Parent Teacher Association and a mom to Crispín.

The state accountability system makes some effort to account for how students who are new to the country impact their schools’ performance. The state excludes English learners, as well as unschooled refugees, during their first year of school in the U.S. from school ratings. The TEA also grades schools based on how students improve on STAAR year over year, which is intended to boost schools that serve low-income communities.

When STAAR performance at a school is precipitously lower than the state average, communities need to take corrective action, said Mary Lynn Pruneda of advocacy group Texas 2036. The state’s accountability system is designed to push districts when they need to make improvements, which can include funneling in more resources before there is a state takeover, she said.

In Houston ISD, the largest school district in the state, the Texas Education Agency replaced the board of trustees and appointed a new superintendent in 2023 after years of failing accountability scores at a single high school.

About 200 miles away from Dobie, the Fort Worth school district is facing a possible state takeover after reaching the threshold for intervention: five years of F ratings at the Leadership Academy at Forest Oak Sixth Grade.

Like Dobie, Fort Worth’s struggling campus drew in many refugees and immigrant newcomers. The district has shut down the Leadership Academy, but TEA Commissioner Mike Morath said the school had already met the conditions for a takeover, making an intervention compulsory.

Shutting schools down should never be a solution to poor academic outcomes, Weeks said. Poor test performance should instead signal a need for more resources and support, he said.

“It’s absolutely wrong. You improve schools instead of punish neighborhoods and children,” Weeks said. “It's not their fault, but they lose.”

Not far from Austin’s Rundberg neighborhood, state lawmakers have returned to the Capitol for a packed special legislative agenda that includes calls for new laws on flood prevention, regulations on THC and redrawn congressional maps.

The 30-day session started July 21, but so far, haven’t yet filed new proposals to revamp the state’s standardized test — and it’s unclear whether they’ll have time to address that with other high-profile issues competing for attention.

During the regular session that ended in June, lawmakers in the House and Senate said the current system isn’t working. But the chambers couldn’t agree on what should replace it.

State Rep. Brad Buckley, a Salado Republican, pushed a bill that would have replaced STAAR with three shorter exams spaced throughout the school year. Supporters hoped the change would ease pressure on students and offer a more accurate picture of learning over time, but negotiations between the two chambers broke down before the regular session ended.

In response to a question about the ongoing legislative push to revamp STAAR, a TEA spokesperson defended the current standardized test, but suggested the agency is open to changes to the accountability system.

“STAAR has been proven to be valid and reliable, but there are other ways to measure learning outcomes,” the spokesperson said. “TEA looks forward to improvements in how we can measure learning in schools across the state.”

Dobie’s invisible wins

Carmen Mendoza had two kids go through Dobie. When her son was bullied, the teachers stepped in all the right ways, she said.

Her daughter, Denisse Badillo, 23, remembers how the school’s community, both in and outside the building’s doors, seemed to wrap their arms around every student. It was easy to get help, even when people didn’t speak the same language.

“I would always want to come to school,” Badillo said. “You would feel safe and secure. The teachers saw us as something other than students.”

Now Mendoza’s nieces and nephews are students there. Families like theirs say the state’s testing and letter grade system doesn’t accurately gauge a school’s success. As legislators revisit how the state measures academic benchmarks and school success, some families look for something more difficult to quantify, like whether the school fosters a safe and welcoming community.

For the Mendozas, success might mean having a bilingual teacher who helps bridge communications between the school and a student’s home, or a principal who knows every student by name.

Parents and teachers also described a campus that had been on the up and up in ways STAAR and the accountability system did not account for. They say improvements came in 2023 when Principal Roxanne Walker stepped into the role after years of staff shortages and unstable leadership. They praised Walker, who once dressed up in an inflatable cowboy costume for a school play and used to toggle between Spanish and English in her speeches to connect with the kids.

Velasquez, the parent of the 12-year-old Dobie student who struggles with dyslexia, said she noticed Walker zeroed in on improving attendance. Velasquez said she would get a call, a text and an email when her son missed school to check in on the family.

“Right when she came in, the new principal just started working a lot, getting kids to come to school, stay in school, and not get out,” Velasquez said. “They had Saturday school — it was a nice program. If he missed class or was late, he could make up for it. That really helped.”

Velasquez also said her rising eighth grader has been more motivated to go to school recently. New programming at Dobie, like barbering and soccer, made a difference for her son.

“They’ve done a tremendous job picking up the school,” Velasquez said. “The faculty, the teachers, the principal — they’ve done a lot of work. I’ve seen the improvements. I’ve seen the hard work. I’ve seen how much they love the students.”

Walker was yet another school staff member who was recently fired and won’t return to the school this fall.

Crispín plans to stay at Dobie for as long as the district lets her. But with so many of her teachers leaving, Castro can tell her daughter is sad.

Crispín is the youngest of her three daughters, all of whom were shaped by Dobie Middle School. Castro’s oldest daughter got a $2,000 scholarship for university when she was at Dobie, which she’s now using to study nursing at Austin Community College.

Castro knows they may not win this fight. But she tells her daughter they have to try.

“We cannot sit back with our arms crossed,” Castro said in Spanish. “We want to keep making history at our school. We can’t let 50 years disappear just like that.”

The Texas Tribune partners with Open Campus on education pathways coverage.

Disclosure: Texas 2036 has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

The lineup for The Texas Tribune Festival continues to grow! Be there when all-star leaders, innovators and newsmakers take the stage in downtown Austin, Nov. 13–15. The newest additions include comedian, actor and writer John Mulaney; Dallas mayor Eric Johnson; U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minnesota; New York Media Editor-at-Large Kara Swisher; and U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, D-El Paso. Get your tickets today!

TribFest 2025 is presented by JPMorganChase.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/SnehaDey_headshot_3x2.jpg)