Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

This story was produced by Grist and co-published with The Texas Tribune.

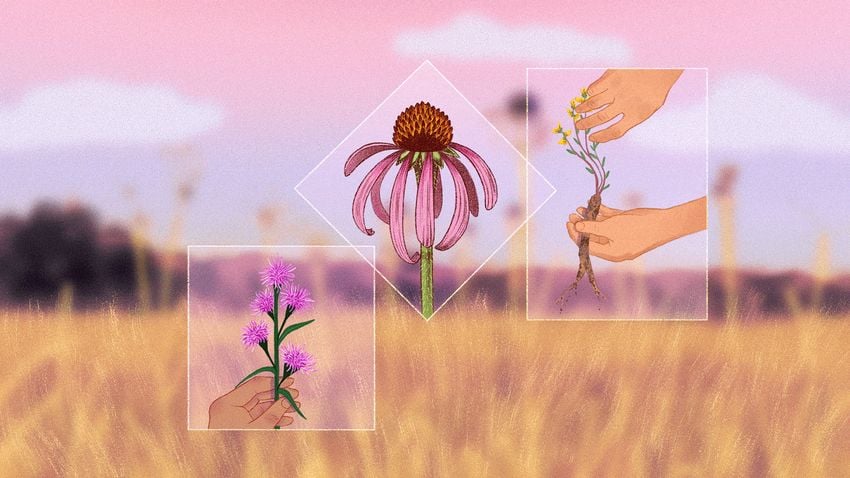

One sunny morning in May, four high school students stood on a flower-dappled prairie in southern Dallas holding shovels. Before them swayed a Texas blazing star, a tall and spindly stalk that erupts in a bottlebrush of purple florets. Max Yan, a senior, made two putts on either side of the imperiled member of the aster family and was beginning to wedge it out when a siren wailed in the distance. He froze, his foot on the blade. There were no fences, no signs warning them off. But the land is, like 97% of the state, private property, and they were, strictly speaking, breaking the law.

“Hopefully that’s not for us,” he said.

The siren faded, and the teens — who attend St. Mark’s School of Texas, an elite, all-boys prep academy on the other side of town — resumed work. They are among the most dedicated members of its prairie club, rising early on weekends to rescue rare plants from bulldozers and move them to restoration sites. Their guerrilla campaign rattles some professional conservationists, but in an era of mounting climate anxiety, it offers a tangible way to make a difference. Not to mention a dose of adrenaline. It is, one said, like “collecting my Pokémons.”

Coneflower Crest, as the boys call this place, after the dusty pink flowers that bloom here, covers nearly 300 acres of undeveloped land believed by some to be the last large intact prairie in Dallas County. Heavy machinery is expected to crush most of it, making way for hundreds of homes and businesses promised to revitalize a neglected corner of Dallas. The developers tout their project’s walkability and eco-friendliness, with ample open space, water-smart landscaping, and native vegetation. But even the greenest projects come at a cost: The city is trading an ecosystem that naturally mitigates the effects of climate change for still more impervious growth that only exacerbates them.

The trend is accelerating across Texas, where blackland prairie once stretched roughly 12 million acres from the Red River to San Antonio — an area nearly twice the size of Vermont. Eons ago, an ancient inland sea sculpted the state’s limestone geology and enriched its soil, sustaining more than 300 species of indigenous grasses and herbaceous flowering plants like big bluestem, lotus milkvetch, and rattlesnake master that fed bison and pronghorn antelopes.

But since European colonization, agriculture and urban development have swallowed 99.9% of the prairie and continue taking their fill. No more than 5,000 acres are left statewide, and last year, a solar farm claimed most of the largest remnant near the Oklahoma border. In Dallas County, which covers some 908 square miles, more than 300 acres have been scraped away since 2014 to make way for everything from data centers and parking lots to high-rises and warehouses — and even a golf course.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/f08ca4f27ce72ba71015643c08083380/Grist%20Urban%20Prairies%20TT%2008.jpg)

All that concrete increases flooding and emissions, depletes aquifers, and compounds the urban heat island effect — the same problems prairies naturally alleviate, said Norma Fowler, a plant ecologist at the University of Texas at Austin. Long grasses and herbs help the ground soak up rain. Their roots reach a depth of 16 feet, producing humus-rich soil that holds water and releases it slowly. Prairies also cool cities, temper the impact of wildfires, and sequester up to one ton of carbon per acre each year. It’s why biodiversity loss and climate change are inherently linked. “Everything we do for conservation is also mitigating the bad effects of climate change,” Fowler said. “If we want to save the planet, it’s not either-or. It’s both-and.”

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

* * *

Environmentalists have rallied to save the region’s grassland since at least the 1980s, when one particularly impassioned fellow patrolled Pioneer Prairie — a 127-acre field off Interstate 30 — with a shotgun. By the 1980s, development of the site loomed, prompting naturalist Ken Steigman to start surreptitiously digging up plants. He even used a sod cutter to roll up ribbons of earth — bugs and all. “It’s like Noah’s ark,” he said. “You are trying to protect everything.”

Plans to replace the prairie with condos stalled amid an FBI investigation of its developers, who were later convicted of loan fraud. Activists rejoiced. Still, development came in bits and pieces, including the construction of a medical complex and a church. In 2019, a native nursery owner named Randy Johnson saw a drilling rig pulling cores for geotechnical analysis, a harbinger of construction. He rode his Honda minibike through its Indian grass as a kid, but by his 20s, reckless joy had given way to wonderment. Johnson worked with the city manager to map its most ecologically sensitive areas, thinking the landowner might build around them, but the bulldozers spared nothing. “It’s one of the most depressing things,” he said with a drawl. “[It’s] something you love and have devoted your life to, and every day you get in your car and see it being destroyed.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/e5acbbfef6ca0c3c3a0455394ffae2ff/Grist%20Urban%20Prairies%20TT%2011.jpg)

He had nearly given up hope when a lanky freshman named Akash Munshi wandered into the St. Mark’s greenhouse, which Johnson tended, that same year. The young man was “hyper,” Johnson said, and extremely bright. Inspired by relatives in south India who cultivate rice, Munshi wanted to learn how to grow food and started a horticulture club. That interest gave way to native plants, and within a couple years, Munshi was as fluent in their Latin names as their common ones.

His senior year, the club began restoring prairie to an acre of bermuda grass along a nearby bike path, a feat that consumed his time outside studies and soccer practice. To source the seeds, he visited local prairies, often after spotting their grassy texture and blinding limestone in satellite imagery. He counted six large sites fated for development, impressing on him a need to salvage as many plants as possible. Within two years, all but one — Coneflower Crest — were stripped bare.

“It was pretty crushing. I didn’t realize how quickly I would lose them,” he said. “There were some sites where there was no sign of development, and I’d come back [the] next week, and the whole thing was scraped.”

The destruction coincides with unprecedented biodiversity loss. Forty percent of all known plants worldwide, and 45% of flowering ones, could be at risk of extinction, and they are disappearing at a rate many magnitudes higher than normal due to human activity and climate change. Those recently discovered — like glandular blazing star, first described in 2001 and found only in Texas — are even more likely to vanish without anyone understanding their role or what benefits they might offer. As populations of at-risk flora shrink, their gene pools become less diverse, making them vulnerable to collapse.

“Each one of those that’s lost is threatening an already under-pressure system,” said Canaan Sutton, a botanist at the National Ecological Observatory Network. The organization collects ecological data to support research on how ecosystems are changing in response to climate change and other factors. Animals of all kinds lose food and habitat when prairies fall, particularly invertebrates with unique relationships to plants they’ve evolved with. There are fewer caterpillars to feed the birds, for example, and fewer bees to pollinate blooms and crops like east Texas’ famed blueberries.

Rescuing doomed individuals can help prevent uncommon species from undergoing “a silent extinction,” Sutton said. Though conservationists focus on collecting seeds, they aren’t always ripe when developers permit harvesting. Some, like hall’s prairie clover, remain so poorly understood that few know how to germinate them. Others, including compass plants, take years to bloom from seed, delaying their availability to pollinators. Keeping a specimen alive helps bridge these gaps. But ultimately, the restoration sites where they live are faint echoes of the vast, complex ecosystem they once knew.

“What we're in now is this perpetually shifting baseline of, ‘This is what we have, and this is as good as it gets,’” Sutton said. “Ultimately, people doing these rescues are trying to move that baseline back in the direction of the past and a more interconnected, natural world — even if that's just [with] a handful of plants.”

* * *

The summer after his senior year, Munshi was leading a high school tour through another prairie destined to become a data center. Stopping for a sip of water, he noticed a tiny yellow flower, which he had previously only read about, standing out against a girl’s black shoe. “Oh shoot!” he said. “That’s Dalea hallii!”

Hall’s prairie clover — a globally imperiled plant listed as threatened by the state — grows on chalky, south-facing slopes of limestone prairies. These patches, an offshoot of the blackland prairie, form where bedrock breaks the surface, creating microhabitats that shelter species found nowhere else. They survived for centuries because the rocky terrain was too difficult to plow. But now, as developers search for more land to build on, that same rock offers an ideal foundation for sprawl.

At the time of Munshi’s discovery, just 59 populations were known to exist on Earth. He counted at least 100 plants and shared his find on Instagram and during a presentation at a meeting of the Native Prairies Association of Texas. It stunned Sutton — then president of the group’s Blackland chapter — and he worked with the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, or BRIT, which banks obscure seeds, to arrange a rescue operation that October.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5dc2dc4fff93717516f6be83437bb49f/Grist%20Urban%20Prairies%20TT%2009.jpg)

The developer gave the crew three hours to dig up what it could. Wearing his customary conical straw hat, Johnson showed more than 40 volunteers how to excavate the plant’s 4-foot-long tap root using knives, pickaxes, sledgehammers, and pneumatic drills. Afterward, he hauled about 300 daleas to his nursery in Forney. Johnson, who is known locally as a plant wizard and, with his long gray hair and narrowed eyes, looks the part, repotted them in soil packed with microbes from bat guano and other things. A month later, he texted Sutton a picture of a flourishing dalea ready for its new home. “He was like, ‘Check it out, dude!’” Sutton said.

To increase their odds of survival, the clover was spread across several sites, including a park, a preserve, and a ranch. More than one-third of those planted on public land survived, a high success rate for such delicate flora. But 180 minutes wasn’t sufficient to save the remaining plants dotting Penstemon Point. So, when Kay Hankins, a conservation botanist at BRIT, offered to contact the developer at Coneflower Crest, Munshi asked her not to, fearing they wouldn’t be given enough time. He and others have spent hundreds of hours relocating thousands of flowers from that site and others to a bike path 30 minutes north — casting any worries about trespassing aside like the rocks they pried loose with their shovels

Despite the questionable legality of their efforts, Munshi said no one has ever confronted them or even asked them to leave. Once, at another location, a passerby suspected him of burying a body and called the police. When the officers saw the plants, they left. “They don’t care,” Munshi said. “They’re literally about to scrape the entire site.”

Johnson fears seeking permission could backfire. A raft of federal protections shields endangered species. Texas offers few for those it lists on its own, and landowners who don’t want the hassle or liability of having them on their property may target them. “This is a war between us and the developers, and nobody’s calling uncle or throwing up white flags,” he said. “You can get out of jail, you can post bail, but once the [plant] genetics are gone, they’re gone, and I’m not going to let that happen if I can help it.”

But some in Texas’ native plant community are uneasy with this approach, arguing that permission is essential for “ethical” digs that promote trust and collaboration with landowners and developers. “If all the experience developers have [with conservationists] is negative, we’ll always be initiating the dialogue from a disadvantaged position,” Hankins said.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/1db97e5052cba2d40ab7d2b559b5a8ff/Grist%20Urban%20Prairies%20TT%2007.jpg)

Developer involvement could ensure that activists don’t inadvertently disturb land that isn’t slated for construction, and more volunteers might help out if it doesn’t involve breaking the law. It also enhances the flora’s value for research and conservation, Hankins said, since reputable institutions, seed banks, and herbaria don’t accept specimens collected without paperwork. As Ashley Landry, who founded the Native Plant Rescue Project near Austin, put it, “We can’t give rare plants to conservation organizations if they’re stolen.”

Landry plays “a long PR game” to gain access. She monitors municipal websites and follows the news to spot new development, then sends emails and snail mail to start a conversation with landowners. She also drives by their property to try catching them in person. In February, her team of 30 volunteers relocated 900 square feet of MoKan, the 30-acre “crown jewel” of Central Texas prairies. Tractors carved out 56 sections, each as thick as a mattress, and stitched them together like quilts at two nearby sites. If the transplants take, the method could be replicated elsewhere.

“I just always feel so thankful to have seen these places before they're gone,” said Landry. “It helps frame your understanding of what the landscape is supposed to look like.”

* * *

Relatively few people can enjoy that experience today — and even fewer are likely to know it in the future. In Dallas, swaths of historic prairie survive in parks, preserves, and the unwanted stretches along utility lines and railroads. Most are tucked away on private land, off-limits to trespassers. These slivers of the past are all that remain there of the grasslands that once waved across the state. The prep school boys now fighting to save what’s left were raised in neighborhoods garnished with greenery from other continents. Some say they grew up without the strong sense of place that environmentalist Wendell Berry has called essential for living in a locale without destroying it.

Like Landry, those who have truly seen Coneflower Crest — not just looked at it, but knelt in its grasses, attuned to its miniscule delights and dramas — have felt changed by the experience. Munshi, now a plant science major at Cornell University, vividly remembers the first time he glimpsed what became his favorite prairie. White rosinweed and Cobea penstemon speckled the grasses, and butterflies flitted amid more echinacea than he had ever seen, suggesting the ground had never been scarred by a plow. “This is, like, a 10!” he exclaimed, filming the scenery. “Imagine what else is in here!”

Leadership of the club he founded, the Blackland Prairie Restoration Crew, passed to Yan, who graduated this spring. He has since handed it off to two boys who joined him in digging up the Texas blazing star and a handful of other beleaguered species. Just two days after their surreptitious dig, a dozen men and women in business suits smiled for the cameras as they scooped shovelfuls of what might be the county’s last expanse or tallgrass. Homes may rise on the pockets that held the greatest biodiversity. Yan and his friends knew this was coming and they understand the need for more housing, but it still saddened them. He dreams of a movement that would push developers to preserve prairies, though such a movement may come too late. "I just don’t know if the prairie will be able to recover at that point," he said. "There are parts of Coneflower Crest that will never be recovered."

Stacked against this tremendous loss, their efforts felt almost trivial. But long after the bulldozers at Coneflower Crest move on to the next job, hundreds of its priceless plants will persist, quivering in the breeze along the bike path. Before Yan and his classmates even transplanted the last of the flora they’d rescued, a few uprooted daleas bloomed in their buckets, rising from the soil toward the sun just as they have always done.

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

The lineup for The Texas Tribune Festival continues to grow! Be there when all-star leaders, innovators and newsmakers take the stage in downtown Austin, Nov. 13–15. The newest additions include comedian, actor and writer John Mulaney; Dallas mayor Eric Johnson; U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minnesota; New York Media Editor-at-Large Kara Swisher; and U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, D-El Paso. Get your tickets today!

TribFest 2025 is presented by JPMorganChase.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.