Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton is handing more of his office’s work to costly private lawyers

This article is co-published with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published. Also, sign up for The Brief, our daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

One day in late May 2024, lawyer Zina Bash spent 6 1/2 hours working on a case against Facebook parent company Meta on behalf of the state of Texas. She reviewed draft legal filings. She participated in a court-ordered mediation session and then discussed the outcome with state Attorney General Ken Paxton.

In her previous job as senior counsel on Paxton’s leadership team, that labor would have cost Texas taxpayers $641.

But Bash had moved to private practice. Paxton hired her firm to work on the Meta case, allowing her to bill $3,780 an hour, so that day of work will cost taxpayers $24,570.

In the past five years, Paxton has grown increasingly reliant on pricey private lawyers to argue cases on behalf of the state, rather than the hundreds of attorneys who work within his office, an investigation by The Texas Tribune and ProPublica found. These are often attorneys, like Bash, with whom Paxton has personal or political ties.

In addition to Bash, one such contract went to Tony Buzbee, the trial lawyer who successfully defended Paxton during his 2023 impeachment trial on corruption charges. Three other contracts went to firms whose senior attorneys have donated to Paxton’s political campaigns. Despite these connections and what experts say are potential conflicts of interest, Paxton does not appear to have recused himself from the selection process. Although he is not required to by law, this raises a concern about appearing improper, experts who study attorneys general said.

Paxton appears to have also outsourced cases more frequently than his predecessors, available records show. And he’s inked the kind of contingent-fee contracts, in which firms receive a share of a settlement if they win, far more often than the attorneys general in other large states, including California, New York and Pennsylvania. Since 2015, the New York and California attorneys general have awarded zero contingent-fee contracts; Pennsylvania’s has signed one. During that period, Paxton’s office approved 13.

One of those was with Bash’s firm, Chicago-based Keller Postman, at the time known as Keller Lenkner, which she joined as partner in February 2021 after resigning from her job at the attorney general’s office. Paxton had signed a contract with the company two months earlier to investigate Google for deceptive business practices and violations of antitrust law. A little more than a year later, Bash’s firm won a state contract to work on the Meta litigation, alleging its facial recognition software violated Texans’ privacy. This time, Bash was the co-lead counsel.

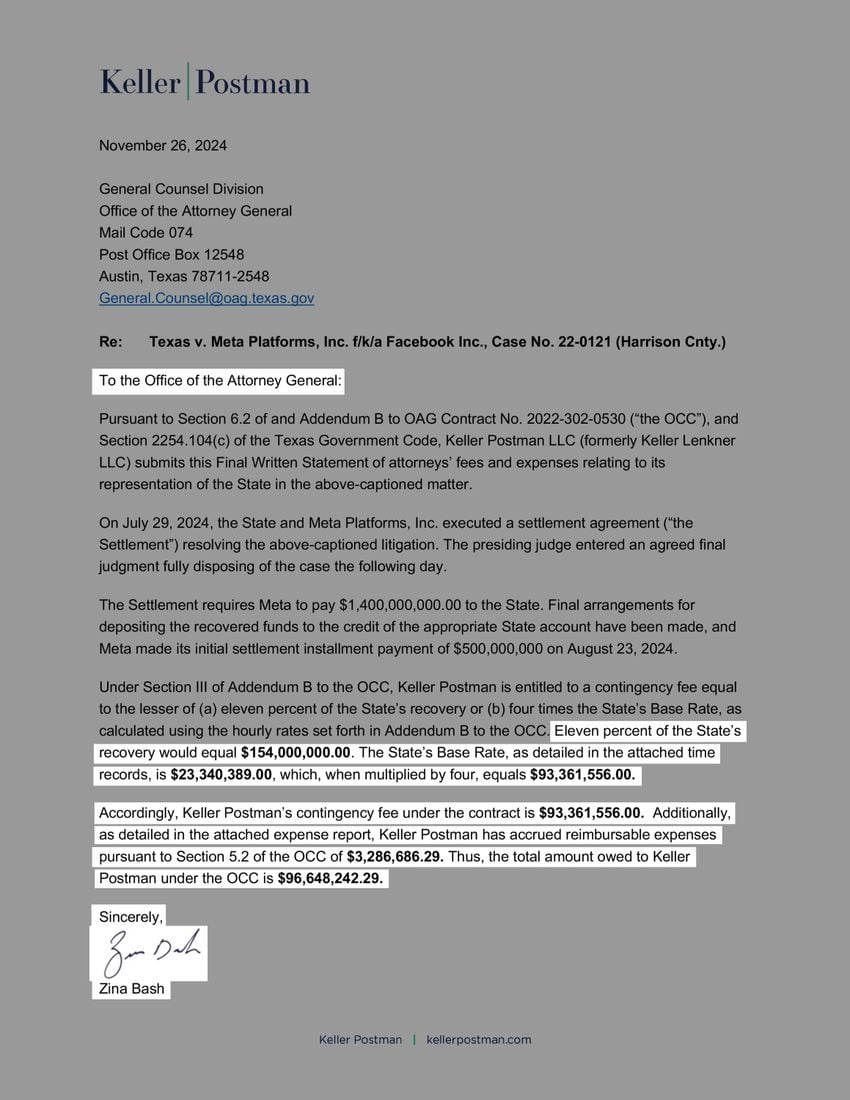

Meta, which called the lawsuit meritless, settled the case for $1.4 billion in the summer of 2024. It was a windfall for Keller Postman. The firm billed $97 million, the largest fee charged by outside counsel under Paxton’s tenure. Bash’s work alone accounted for $3.6 million of that total.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Bash, a former U.S. Supreme Court clerk, said in a statement she is honored the attorney general’s office partnered with Keller Postman based on the firm’s “first-rate attorneys and extensive experience.”

“We have a record of taking on the most significant litigation in the country against the most powerful defendants in the world,” Bash said.

Keller Postman did not respond to a request for comment.

There is little to stop Paxton, or any other occupant of his office, from handing these contracts out. The attorney general can award them without seeking bids from other law firms or asking anyone’s permission.

Asked to provide competitive-bid documents for the contingent-fee contracts it has awarded, the attorney general’s office said it had none because state law “exempts the OAG from having to do all of the solicitation steps when hiring outside counsel.”

Given the high-profile nature of representing an attorney general and the potential for a big payday, many qualified firms would be eager to compete for this work, said Paul Nolette, a professor of political science at Marquette University who studies attorneys general.

“I’d be curious to know what the justification is for this not going on the open market,” Nolette said.

Paxton declined interview requests for this story. He has publicly defended the practice of hiring outside law firms, arguing that his office lacks the resources in-house to take on massive corporations like tech companies and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

“These parties have practically unlimited resources that would swamp most legal teams and delay effective enforcement,” Paxton told the Senate finance committee during a budget hearing in January.

A spokesperson for Paxton said in a statement that the outside lawyers hired by the office are some of the best in the nation. With the contingent-fee settlements to date, more than $2 billion, the state “could not have gotten a better return on its investment,” the statement said.

Chris Toth, former executive director of the National Association of Attorneys General, questioned why so much extra help is needed. Outside counsel is appropriate for small states, he said, that “only have so many lawyers with so many levels of expertise.”

The Texas attorney general’s office, one of the largest in the country, has more than 700 attorneys.

“Large states typically don’t hire outside counsel,” Toth said. “They should have the people in-house that should be able to go toe-to-toe with the best attorneys that are out there.”

A troubled history

When a Texas attorney general previously made a practice of giving lucrative contracts to private counsel, it didn’t end well.

Dan Morales was the last Democrat to hold the office. He became embroiled in scandal after he used outside firms to help secure a $17 billion settlement in Big Tobacco litigation in 1998.

Republicans, including then-Gov. George W. Bush, blasted the $3.2 billion payout to the outside lawyers as exorbitant. Their attacks grew more intense when Morales sought to steer $500 million of that sum to a lawyer, a personal friend, who did very little work on the case. Morales pleaded guilty in 2003 to related federal corruption charges. He served 3 1/2 years behind bars.

John Cornyn, the Republican who succeeded Morales in 1999, criticized his predecessor’s handling of the tobacco case during his campaign for the office. In an interview for this story, Cornyn said he never hired outside counsel as attorney general because he focused on recruiting talented in-house lawyers that he felt could handle all the office’s cases.

Paxton is challenging Cornyn, now a four-term U.S. senator, in next year’s Republican primary.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, the Republican who led the office after Cornyn, appears to have rarely used private lawyers. The attorney general’s office was able to produce records for only part of Abbott’s 12-year term because state law allows the files to be deleted after so many years. The office signed nine outside counsel contracts between 2010 and 2014, all pro bono or for hourly rates rather than contingency. Abbott did not respond to an interview request.

Paxton also seldom outsourced cases during his first five years in office. Through 2019, he awarded only nine outside counsel contracts, all pro bono or hourly rate. The most expensive contract capped fees at $500,000 — far less than $143 million the state paid to the two firms, including Bash’s, that handled the Meta case.

He changed course in 2020.

That summer, the attorney general’s office was gearing up to file its first case against Google. It related to allegations that the company monopolized the online advertising market, raising costs for advertisers, who increased the price of their products for average consumers as a result. Paxton initially had no plans to hire outside counsel for the litigation, three former deputy attorneys general told the Tribune and ProPublica.

But before the case was filed, the attorney general’s office was thrown into upheaval. At the end of September, seven of Paxton’s senior advisers reported him to the FBI, concerned his relationship with an Austin real estate investor had crossed the line into bribery and corruption. State House members would later impeach Paxton on counts related to the accusations; state senators eventually acquitted him. The federal criminal investigation into Paxton did not result in any criminal charges.

Over fall 2020, each of the lawyers in his office who had accused Paxton of wrongdoing quit or was fired. That included Darren McCarty, the head of civil litigation who was supposed to lead the Google litigation before he reported his boss to the FBI. He resigned on Oct. 26.

Less than two months later, on Dec. 16, Paxton signed contracts with The Lanier Law Firm and Keller Postman to investigate Google. They filed the lawsuit against the tech giant in federal court the same day.

Paxton replaced the lawyers who complained to the authorities. The staffing of the antitrust and consumer protection divisions, which would have handled these cases, remained constant at more than 80 employees in the following years. Yet Paxton continued to outsource lawsuits against large corporations to private lawyers.

Under Keller Postman’s contract, the firm would be paid only if it secured a settlement or won at trial. These contingent-fee cases have the potential to be far more profitable for the outside firms than those in which they bill at a regular hourly rate. In a successful case, the contracts say that firms are paid either a percentage of a settlement or the sum of hours billed by the firm times four, whichever is less.

In the Meta case, Keller Postman was entitled to 11% of the state’s settlement, a share that totaled $154 million. But because the firm’s fees and expenses totaled $97 million, it billed that sum.

In multiple legislative sessions, Paxton has testified that outsourcing was the only way his office could stand toe-to-toe with corporate titans.

If Paxton has a shortage of qualified in-house attorneys, Cornyn told the newsrooms, that’s because of the damage the whistleblower scandal did to the reputation of the attorney general’s office as a home for ambitious young lawyers.

“He’s a victim of his own malfeasance and mismanagement because people did not want to work for him anymore,” Cornyn said. “And if you run off your best lawyers because you engage in questionable ethical conduct, then you’re left with very few options. But this shouldn’t be a way to reward bad behavior.”

Former Arizona Attorney General Terry Goddard said he was surprised Paxton began hiring contingent-fee outside lawyers only after the scandal, since those contracts, with their potential for high profits, are tougher to ethically defend.

“I would have thought it would have been the other way around — that he got more careful after he got the whistle blown on him,” said Goddard, a Democrat. “But it looked like he got more reckless.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/69c186400e43dc4647e534f99e7ee9ec/0915%20%20Impeach%20Trial%20Day%209%20JS%2021_preview_maxWidth_3000_maxHeight_3000_ppi_72_embedColorProfile_true_quality_95.jpg)

Connections to contract recipients

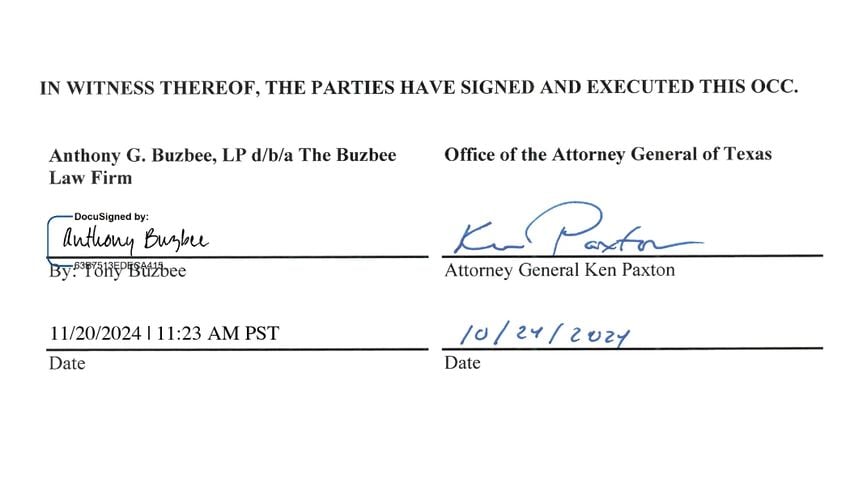

Paxton’s style of procurement also benefited Buzbee, the man who successfully defended him during his impeachment trial, which stemmed from allegations the whistleblowers raised.

The attorney general chose to skip most of the proceedings, so for the 10 days of trial in the Texas Senate, his most vociferous advocate was the loquacious Buzbee. The pair sat side by side when the attorney general did attend.

A little more than a year later, Paxton hired The Buzbee Law Firm to pursue an antitrust suit against the investment firms BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard that accuses the companies of manipulating the coal market in a way that allegedly increased electricity prices for Texans. The firms deny wrongdoing.

Buzbee is a successful litigator and one of Houston’s most famous plaintiffs’ attorneys. Among other victories, he won settlements for victims of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and $73 million for Gulf of Mexico oil drillers in a 2001 antitrust case. But he’s known primarily for personal injury work, not antitrust litigation.

His firm, one of two hired for this latest attorney general’s office contingent-fee case, could collect 10% of any judgment or settlement. The case is in its early stages, though the Trump administration in May filed a brief in the case in support of Texas.

Buzbee downplayed the potential for a big payday in an email to the newsrooms and argued there is no buddy system at play, noting he believed other law firms also interviewed with Paxton’s office for the job. (The attorney general’s office did not confirm this.) He said his firm has to pay for significant expenses up front, without any guarantee of payment.

“The current arrangement may be a good deal for other lawyers, but in all candor, it’s not for me,” Buzbee said, adding that his normal hourly rate is $2,250. “Frankly, the only reason I’m even doing it is that I am proud to represent the state in such a landmark case.”

The connections between Paxton and the lawyers he has hired also extend to other firms. The attorney general’s office hired the firm Norton Rose Fulbright, one of the largest in the country with more than 3,000 lawyers on staff, to work on separate Google cases for the state, focusing on consumer protection allegations.

The attorney general’s office has awarded three contracts to the firm since 2022 for cases against the tech giant. Three times during that period, Joseph Graham, the firm’s lead counsel on the Google litigation, contributed $5,000 to Paxton’s campaign for attorney general. Twice, the donations came within 16 days of Graham signing one of the firm’s contracts with the attorney general.

The firm and its attorneys have contributed $39,500 to Paxton’s campaign since he took office. Neither Graham nor Norton Rose Fulbright responded to requests for comment.

Mark Lanier, founder of The Lanier Law Firm, which the state hired to work on a separate Google case, is a large donor to Texas elected officials. He has contributed $31,000 to Paxton’s campaigns since 2015. The largest contribution, for $25,000, came six months after Lanier signed his firm’s Google contract.

The Lanier contract is slightly different from the others the attorney general’s office awarded, in that the firm’s payment is partially based on a basic hourly rate but it could also be paid more if it wins the case, as in the contingent-fee model. Lanier noted in an emailed statement to the newsrooms that he took a reduced fee on this case and maintained that the attorney general’s office needed the kind of firepower his team can bring against an opponent like Google.

“The Texas AG office and its lawyers are good, but specialists are needed in a war like this. And it is a war,” Lanier wrote. “It would be irresponsible to pursue Google on behalf of Texans without bring[ing] the fullest resources you can.”

A competitive, open process for awarding contracts can be a strong defense against accusations of favoritism, Goddard said.

Unlike some other states, Texas does not require these contracts be put out to competitive bid.

Florida, for example, has one of the most robust laws in the country for procuring outside counsel, requiring the attorney general to explain in writing why a contingent-fee contract is necessary. It also mandates most contracts be put out to competitive bid and caps contingent-fee payouts at $50 million.

Texas has no such cap.

It also has virtually no method for state lawmakers to truly supervise this kind of practice. State law mandates only that the attorney general notify the Legislature when his office awards a contingent-fee contract, and certify that no in-house lawyers or private attorneys at an hourly rate can handle the task. Paxton has done so in boilerplate two-page letters that all say outside attorneys are needed because of the “scope and enormity” of the cases.

If lawmakers are concerned about these contracts, there is no mechanism for them to challenge Paxton’s determination that private counsel is needed.

Having lawyers bid for work would eliminate the appearance of impropriety that hangs over Paxton’s hires, Goddard said.

“A couple look like paybacks, which is extraordinarily improper, in other words to award a contract to someone who’s a major contributor or has recently left your office,” he said. “All of those would not be allowed in our state.”

Officials in other states have said they can still secure big wins for their constituents without relying on private firms.

California, for example, reached a $93 million settlement with Google in 2023 over claims that the company was clandestinely tracking users’ locations. A year earlier, in a case with similar allegations, Oregon and Nebraska led a 40-state coalition that won a $392 million settlement against the company. Texas was not part of this suit.

The latter agreement required Google to make new privacy disclosures to consumers, restricted its ability to share users’ location information with advertisers and required the company to prepare an annual report detailing how it was complying with the settlement terms.

Doug Peterson, the Republican attorney general of Nebraska at the time, said negotiating the financial penalty — Nebraska’s share was $11.9 million — was a secondary goal of the settlement.

“The most important thing we’re trying to do is to stop the bad behavior,” Peterson said.

McCarty, one of the attorney general employees who blew the whistle on Paxton, said private lawyers can be talented, but they have an incentive to fixate on the financial portion of settlements — which is tied to their compensation — rather than enforcement provisions that may best protect a state’s residents.

“Government enforcers, especially in the antitrust context, can focus on more effective solutions,” McCarty said.

Norton Rose Fulbright has yet to send its final billing records to the attorney general’s office but is likely to be rewarded handsomely. The firm helped the state secure a $1.38 billion settlement with Google in May. Google spokesperson José Castañeda said the Texas settlement, which has not been finalized, will contain no new restrictions on the company’s practices.

Under the terms of its contracts, the firm’s fees could exceed $350 million.

Disclosure: Facebook and Google have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

The lineup for The Texas Tribune Festival continues to grow! Be there when all-star leaders, innovators and newsmakers take the stage in downtown Austin, Nov. 13–15. The newest additions include comedian, actor and writer John Mulaney; Dallas mayor Eric Johnson; U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minnesota; New York Media Editor-at-Large Kara Swisher; and U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, D-El Paso. Get your tickets today!

TribFest 2025 is presented by JPMorganChase.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Zach_Despart_HC_TT_02.jpg)