The Taking

The Taking, illustrated: A Texas family's story of losing land for the border fence

By Susie Cagle, ProPublica

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/12/19/tt-propublica.png)

The Taking

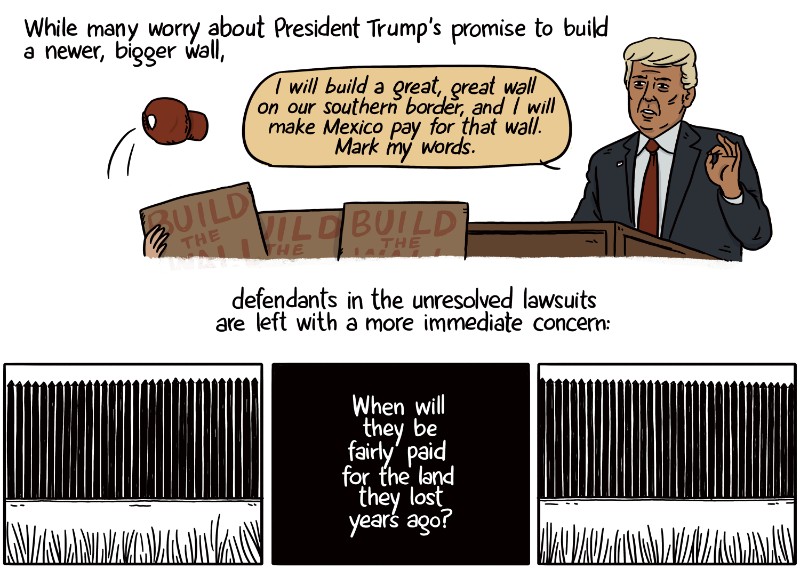

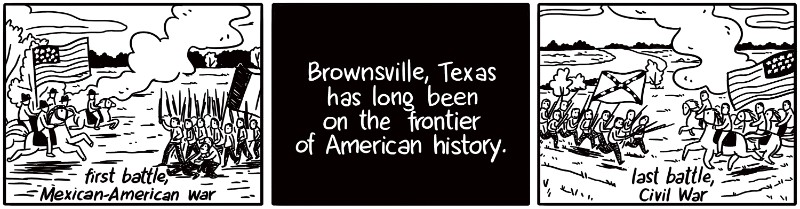

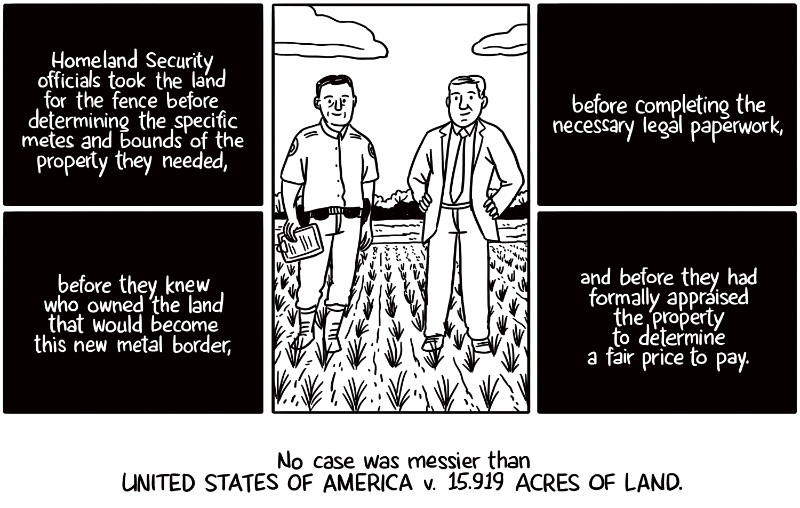

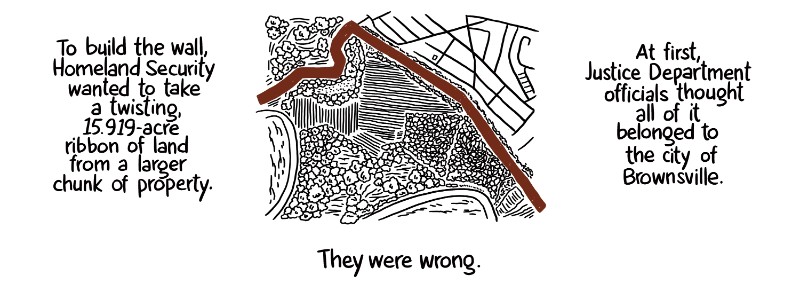

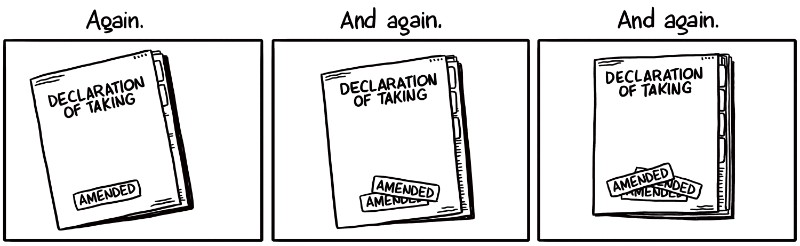

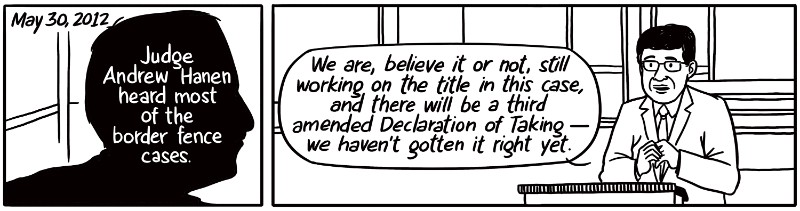

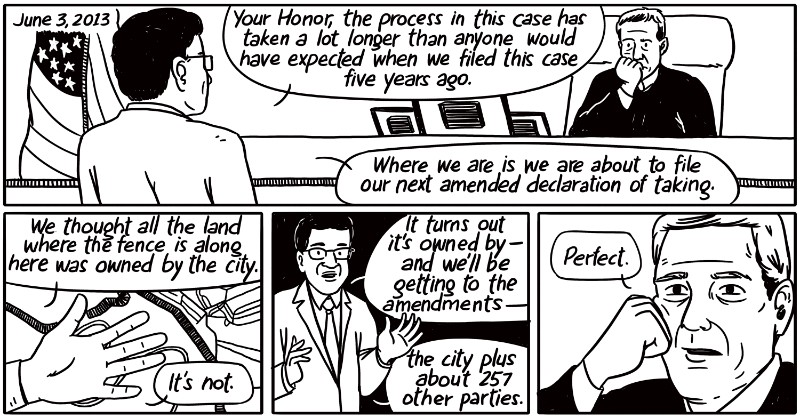

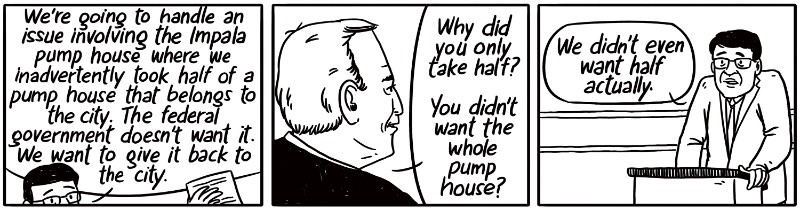

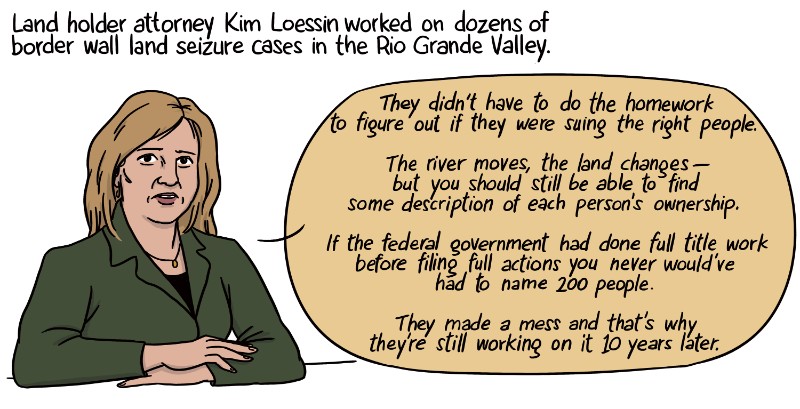

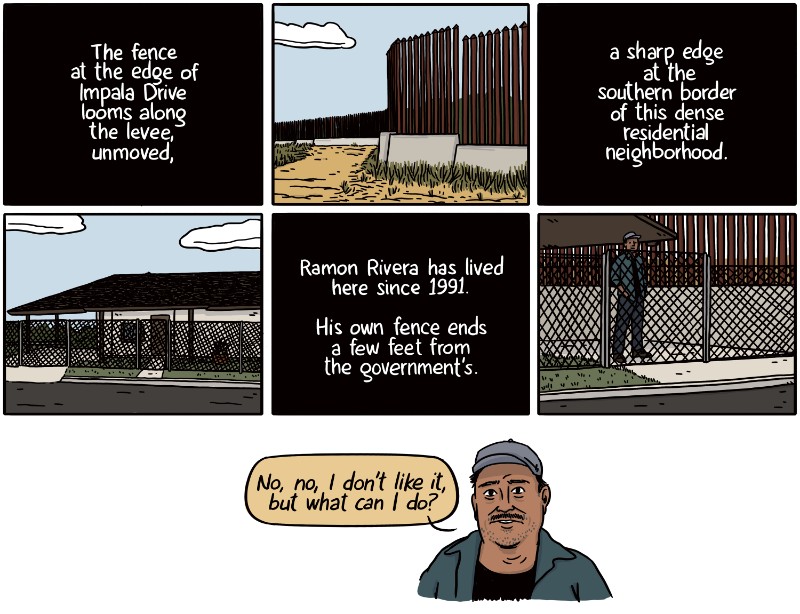

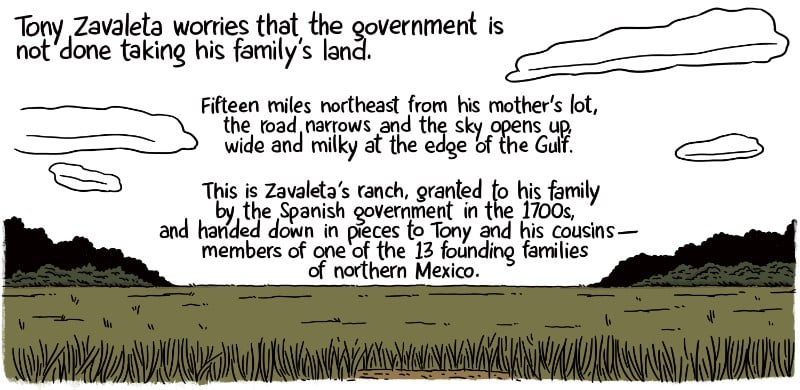

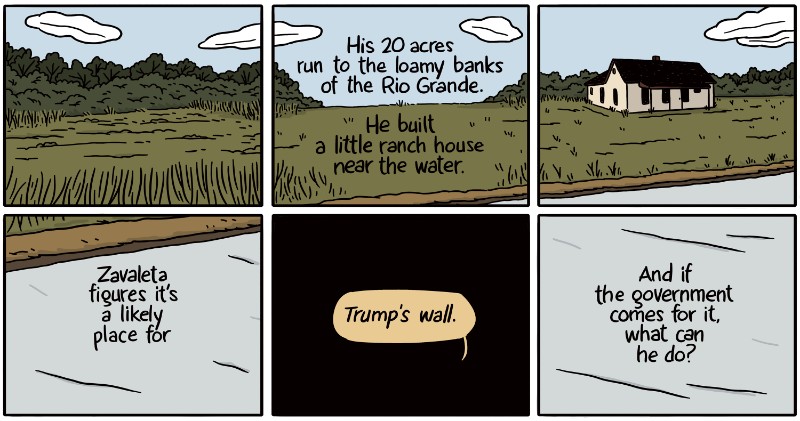

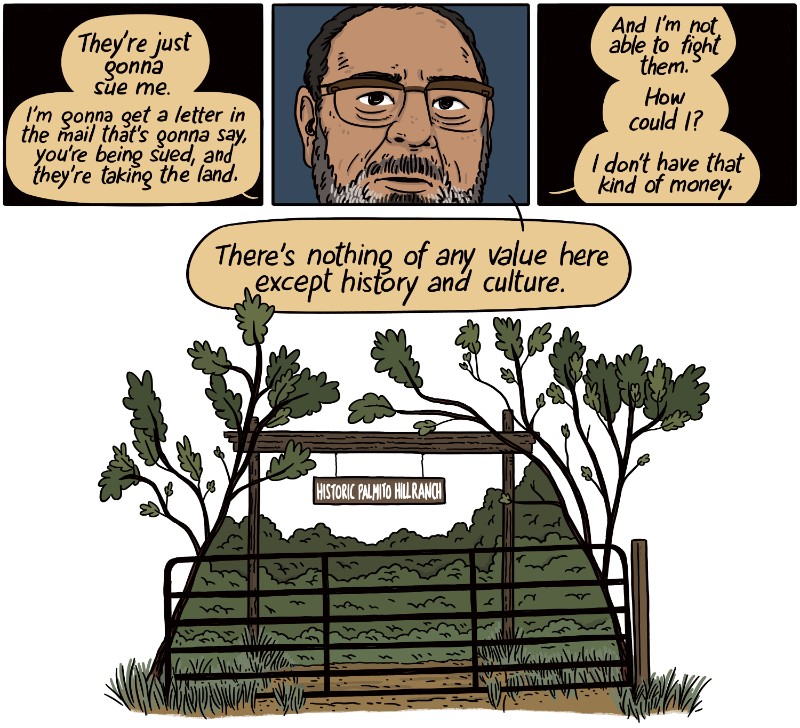

Inside the federal government's haphazard, decade-long process of seizing private land for a border fence.

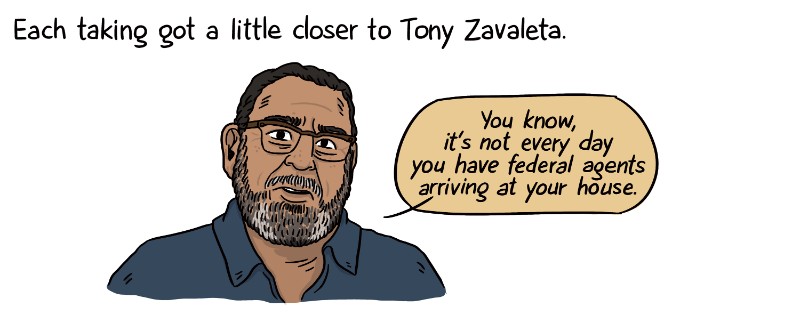

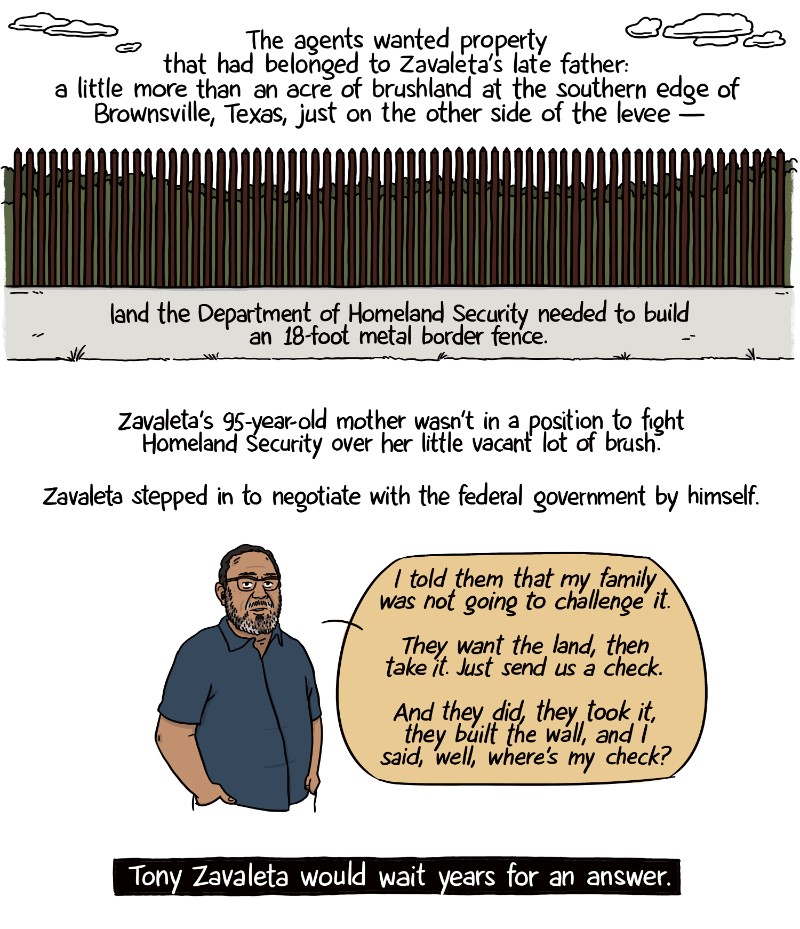

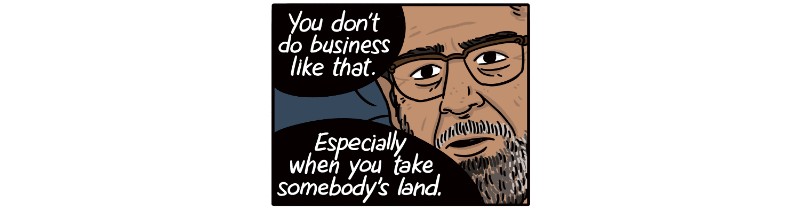

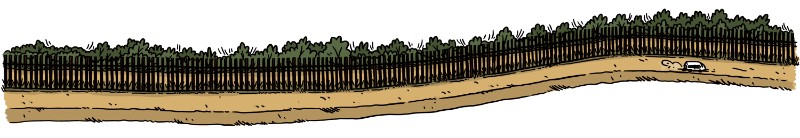

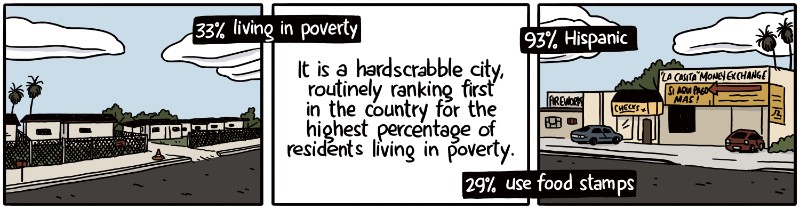

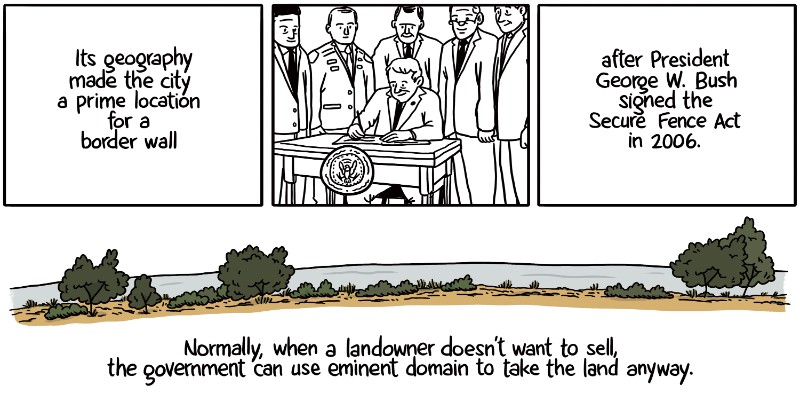

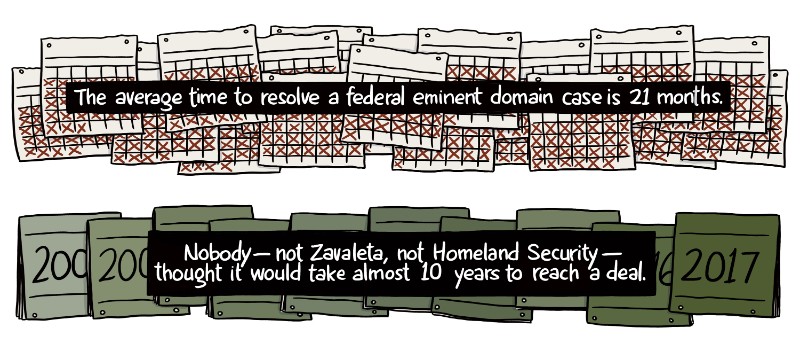

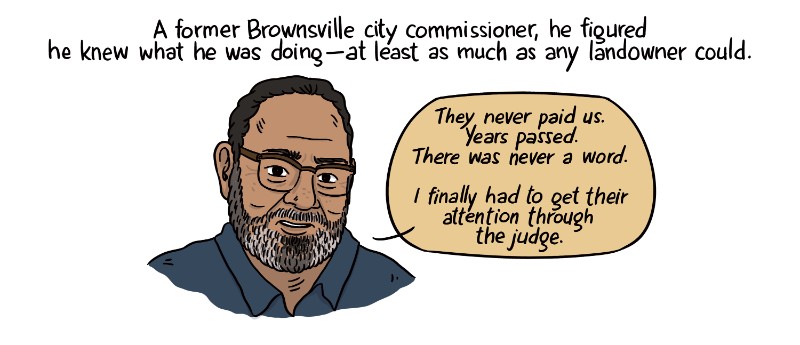

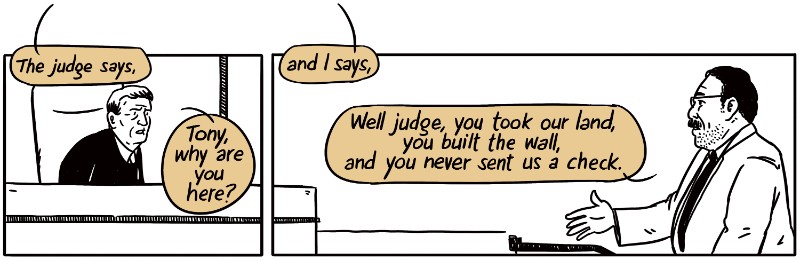

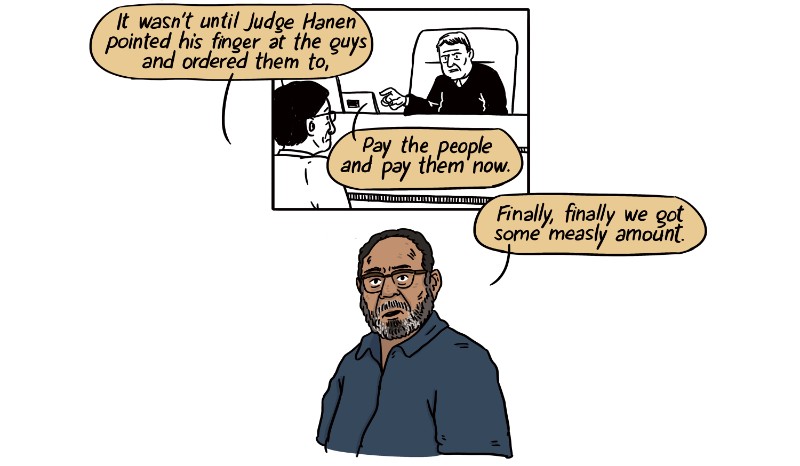

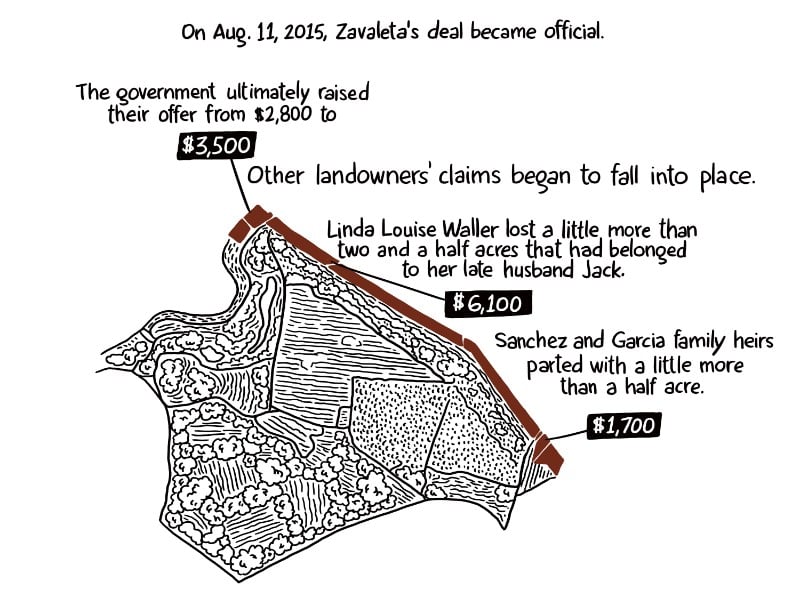

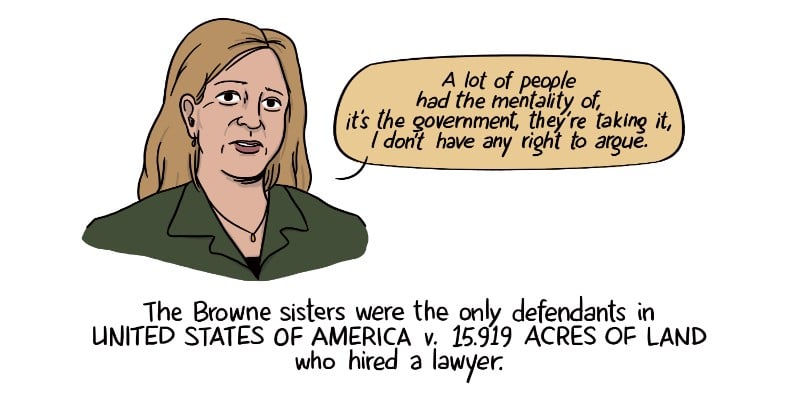

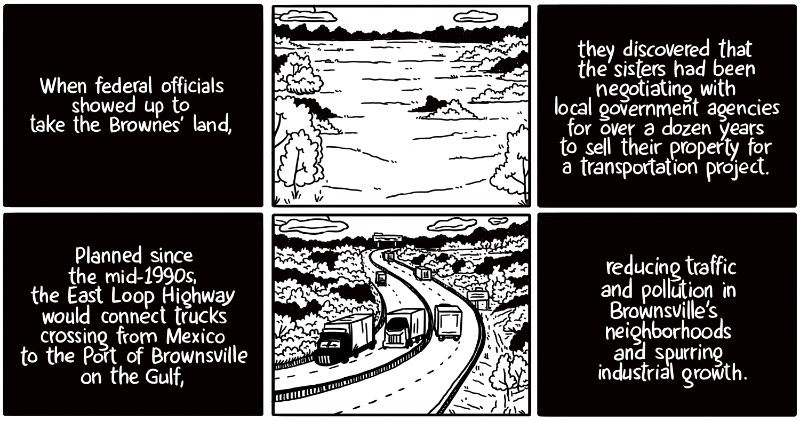

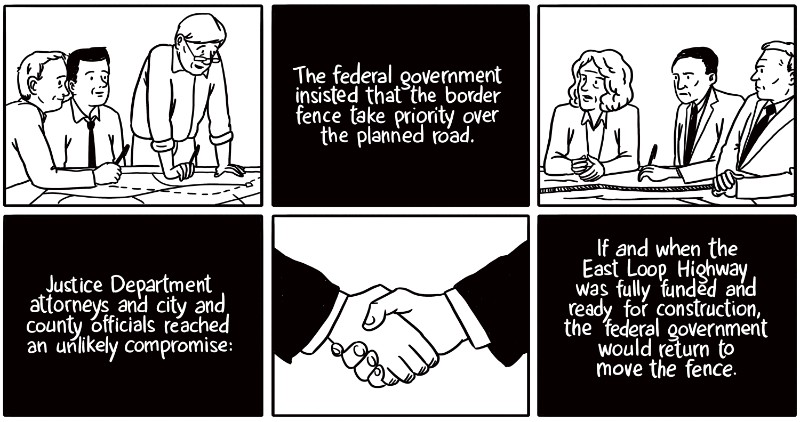

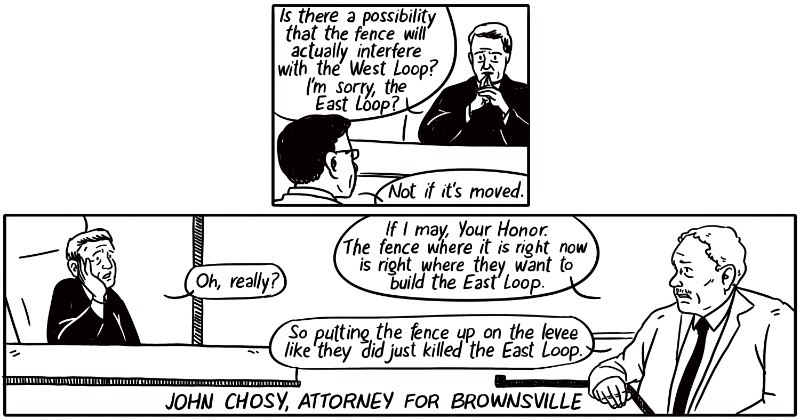

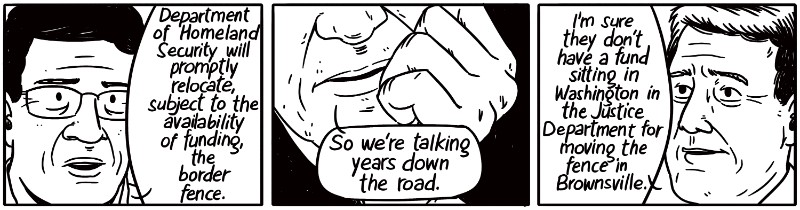

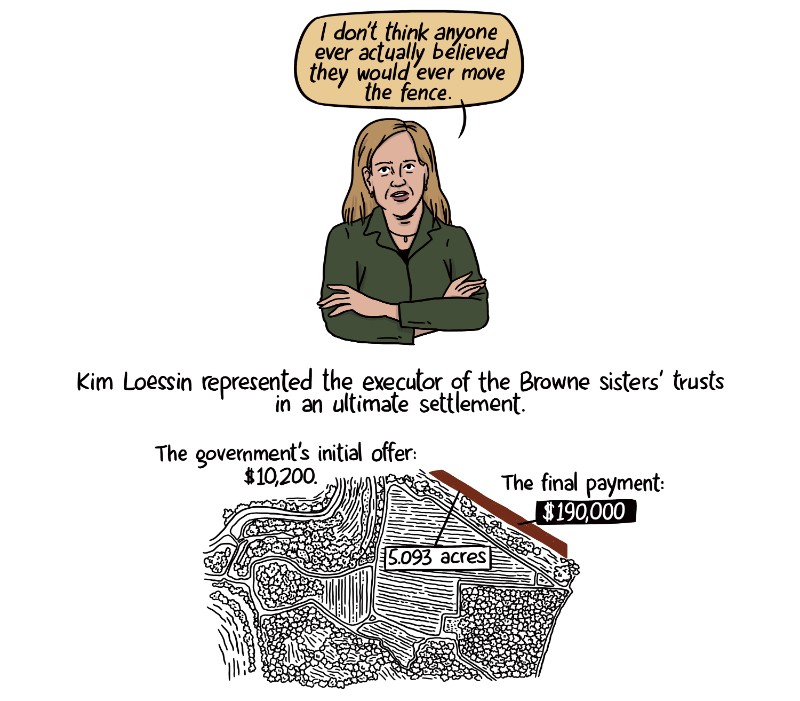

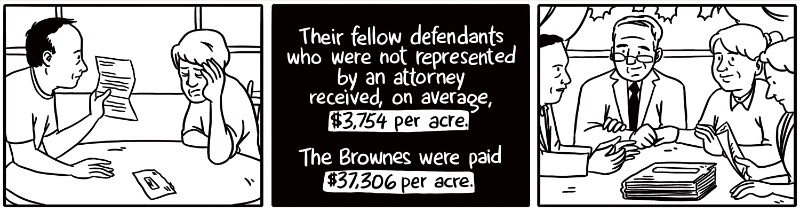

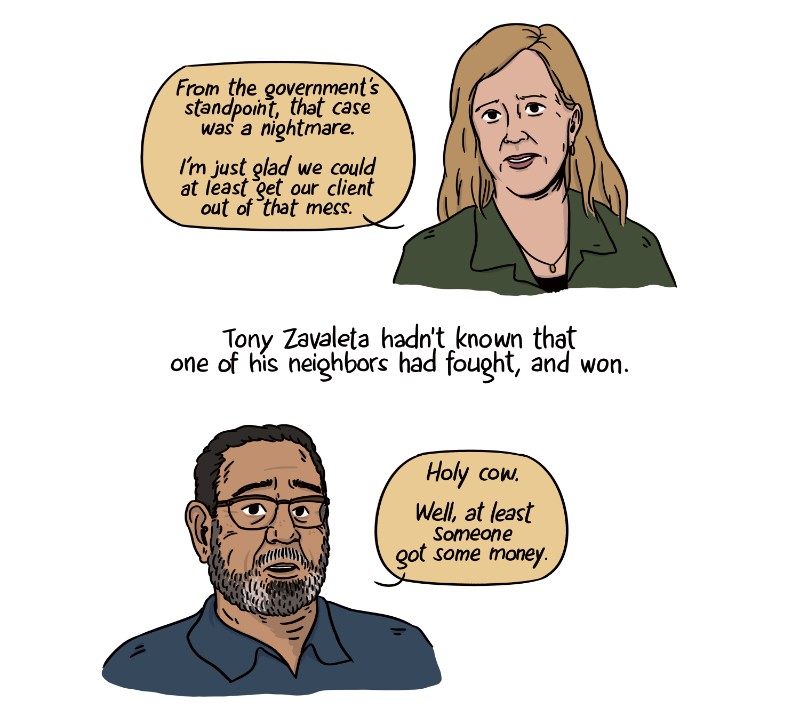

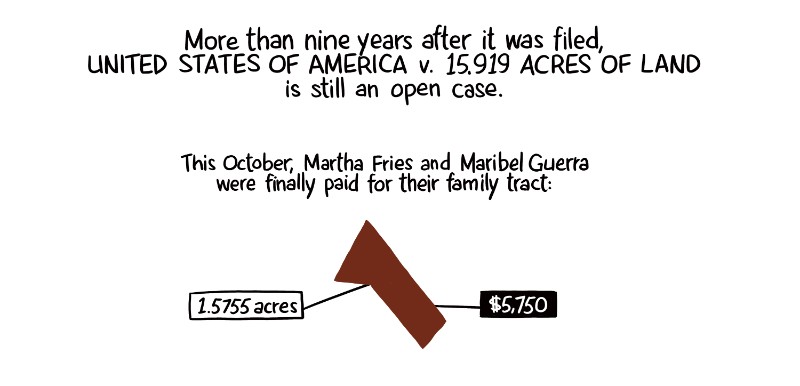

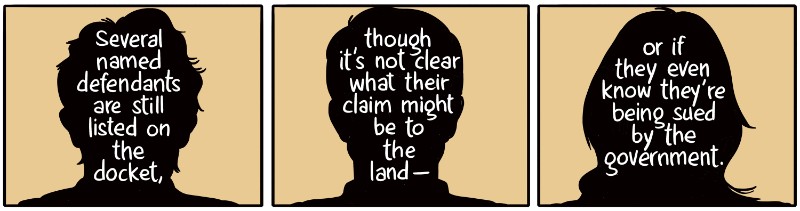

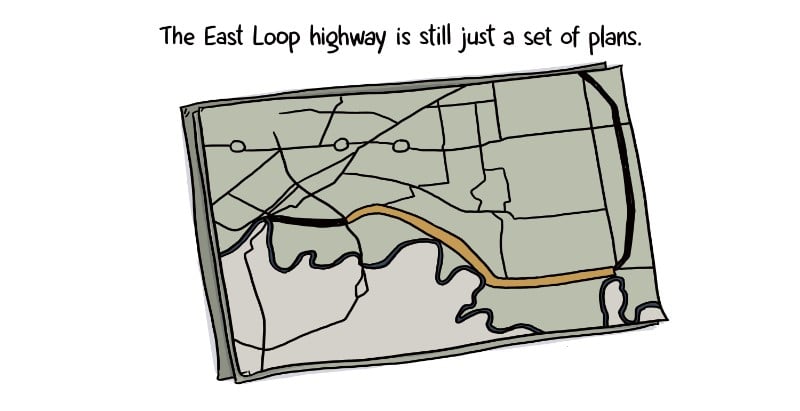

More in this seriesIn 2007, the Department of Homeland Security began building 654 miles of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border. To complete the job, the agency had to seize land from private landowners, most living in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. A decade later, some landowners have yet to reach agreement with Homeland Security on the amount they are due for the land they have lost. This is the story of one such case.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.