After a quiet year of campus carry, community colleges get guns next

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/07/29/APrice-GunFreeUT-7.jpg)

Janeera Nickol Gonzalez was shot on a Wednesday in May, in the late morning. She died in a study room in Performance Hall, a multistory brick structure on the campus of North Lake College, outside Dallas. Gonzalez was 20 years old; she would have been the first in her family to graduate from college.

Starting Tuesday, a gun like the one that took her life can be legally carried — in a hidden holster, or tucked into a waistband, or in a backpack — into Performance Hall, along with most other buildings at the six dozen community colleges in Texas. Senate Bill 11 — which allows licensed individuals to carry concealed handguns into most campus buildings and went into effect a year ago for public universities — now becomes law at two-year colleges. Schools have the discretion to declare certain buildings gun-free for legitimate safety reasons.

Depending on whom you ask, the fact that guns may be carried into Performance Hall and buildings like it is either an important assertion of freedom or an affront to the very character of higher education. And one opinion informs the next: Would SB 11 have saved Gonzalez’s life? Was it ever SB 11’s job to save her life?

As schools navigate the new landscape, they face not only the peculiar challenges of regulating guns on community college campuses — the quirks and confusions that led lawmakers to grant two-year colleges an extra year for planning — but also find themselves in the midst of a guns-on-campus debate that rages on even after a year free of disaster.

A quiet year

Community colleges are armed with at least one advantage: They have gotten to spend the last year observing how the law has played out on four-year university campuses.

And that year was relatively quiet.

Perhaps the loudest interruption came on a warm Wednesday evening in September, when a shot rang out in Integrity Hall, an airy, brick upperclassman dorm at Tarleton State University in Stephenville. The discharge injured no one and caused minimal property damage.

“Other than the accidental discharge incident, campus carry was implemented at Tarleton very smoothly and without incident,” said Harry Battson, Tarleton’s assistant vice president for marketing and communications. “Not sure there’s anything I can add to that.”

Battson’s attitude is representative.

“Virtually no impact at all,” is how Chris Meyer of Texas A&M described campus carry’s effect.

“Amazingly quiet,” said Texas Tech University President Lawrence Schovanec.

“I expected it to be largely uneventful, and those expectations have been pretty much borne out,” said Phillip Lyons, dean of the Sam Houston State University College of Criminal Justice.

A review of gun-related incidents through open-records requests submitted to the state’s large research schools shows no sharp increase in violence or intimidation. A typical campus looks something like the UT Health Science Center at Tyler, which had exactly one gun-related incident in the 12 months before campus carry was implemented, and exactly one in the year following. In both cases, a patient brought a gun to a doctor’s appointment — where it remains illegal to carry even a concealed weapon — because of confusion about the statute. Neither resulted in charges.

Drive 500 miles west to Texas Tech, and over the same period, the number of gun-related incidents changed from five to six.

The uneventful implementation follows the patterns of the seven other states that legalized campus carry before Texas. But even a year’s worth of data is not enough to draw definitive conclusions, administrators said.

“I don’t know if you’re ever really going to be able to determine that as a fact: Is it safer or is it not as safe?” said Vicki Brittain, a Texas State political science professor who led campus implementation efforts. “That may always be in the area of opinion.”

The year’s biggest campus security threat, at the University of Texas at Austin, came not from a gun but from a Bowie-style hunting knife, when on May 1, junior biology major Kendrex White stabbed four people, killing freshman Harrison Brown.

The incident has been twisted into various political pretzels to argue for various viewpoints. Was the problem that there were too many weapons on campus that day, or not enough? Would the tragedy have looked any different a year earlier?

But the true nightmare situation — a mass campus shooting, with concealed carriers shooting a ricochet of confused bullets that make it impossible for police to sort the innocents from the aggressors — has not materialized. The law’s practical impact was relatively small; only licensed gun owners, who must be older than 21 and meet various eligibility requirements, are permitted to carry. A UT committee estimated that less than 1 percent of students on the Austin campus would be licensed.

And administrators overwhelmingly say the change to campus climate has been minimal, if it was noticeable at all. As “Gun Free UT” signs begin to yellow and fall from campus windows, there are few echoes of the vehement protests staged before the law’s implementation.

A year into its effectiveness, and at the cusp of its implementation at junior colleges, the law seems to have faded from public attention.

Immeasurable impacts

Anti-gun activists would list the following casualties: Nobel Laureate Thomas Südhof, who turned down a spot at UT-Southwestern partially because of “the constant danger that a gun will be pointed at me any minute”; media scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan, who withdrew from consideration to be Moody College of Communication’s dean, citing campus carry as a "major reason"; Daniel Hamermesh, a former UT economics professor now teaching in London because of concerns that a disgruntled student might “start shooting at me.” And perhaps the most famous case: Fritz Steiner, who left after 15 years as the dean of UT-Austin’s architecture school, in favor of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design — and Pennsylvania’s more restrictive gun laws.

"I would have never applied for another job if not for campus carry," Steiner said last year.

It’s impossible to know exactly how many scholars have turned down, or declined to even consider, positions at Texas two- and four-year schools since SB 11 passed in 2015. It’s impossible to count the students who didn’t apply to Lone Star State colleges.

For those against campus carry, the law’s impact on recruitment is yet another cause for outrage. Those in favor of SB 11 argue that the problem is not campus carry but rather “paranoia about campus carry.” (That there is an impact on recruitment is one of the few facts both sides can agree on.)

UT-Austin President Gregory Fenves has described “significant concerns” about whether the law would hurt the flagship state university’s efforts to court top talent. Asked whether the law has made it harder to recruit, Steven Goode, the UT law professor who chaired the university’s working group on campus carry, gave a flat and immediate “yes.”

“There’s already a hesitation that people have about coming to Texas given the political environment,” he said. “I think it was a product of campus carry fitting into a narrative about Texas. And it’s a narrative that some number of potential faculty find unpalatable.”

Some instructors have fought the law, holding office hours at bars where concealed carry is prohibited, or declaring their offices gun-free zones.

Some have taken it even further. Last July, three UT Austin professors sued the state and the university, claiming that the potential presence of guns in classrooms has a “chilling” effect on class discussion, especially when seminars turn to heated or sensitive topics. A federal judge dismissed that claim earlier this summer, saying professors could not present any “concrete evidence to substantiate their fears” that campus carry breeds fear in classrooms.

It’s a familiar debate. Opponents of the law describe fear, tension and quieter seminar tables; gun advocates insist the “new normal” is identical to the old. But that’s all anecdotal, and almost all ideological. There isn’t yet evidence from the year that can declare a definitive victor in the data debate.

For the law’s author, state Sen. Brian Birdwell, R-Granbury, the law is about principle; personal safety is a happy but secondary consequence. Quinn Cox, president of UT-Austin's chapter of Students for Concealed Carry, argues that “the burden of proof rests on those trying to deny a right rather than those trying to grant one.” Without proven harm, “no one has the right to deny me this,” Cox said.

The three professors disagree on both counts: There is evidence of harm, they say, and evidence sufficient for prohibiting guns. They will appeal their case this fall to continue making that argument.

“Our issue is: What more do you want, unless it’s disaster?” questioned Renea Hicks, the professors’ attorney. “You don’t have to be killed to be chilled in this situation. The ‘chilling’ can be short of that disastrous consequence.”

The challenges ahead

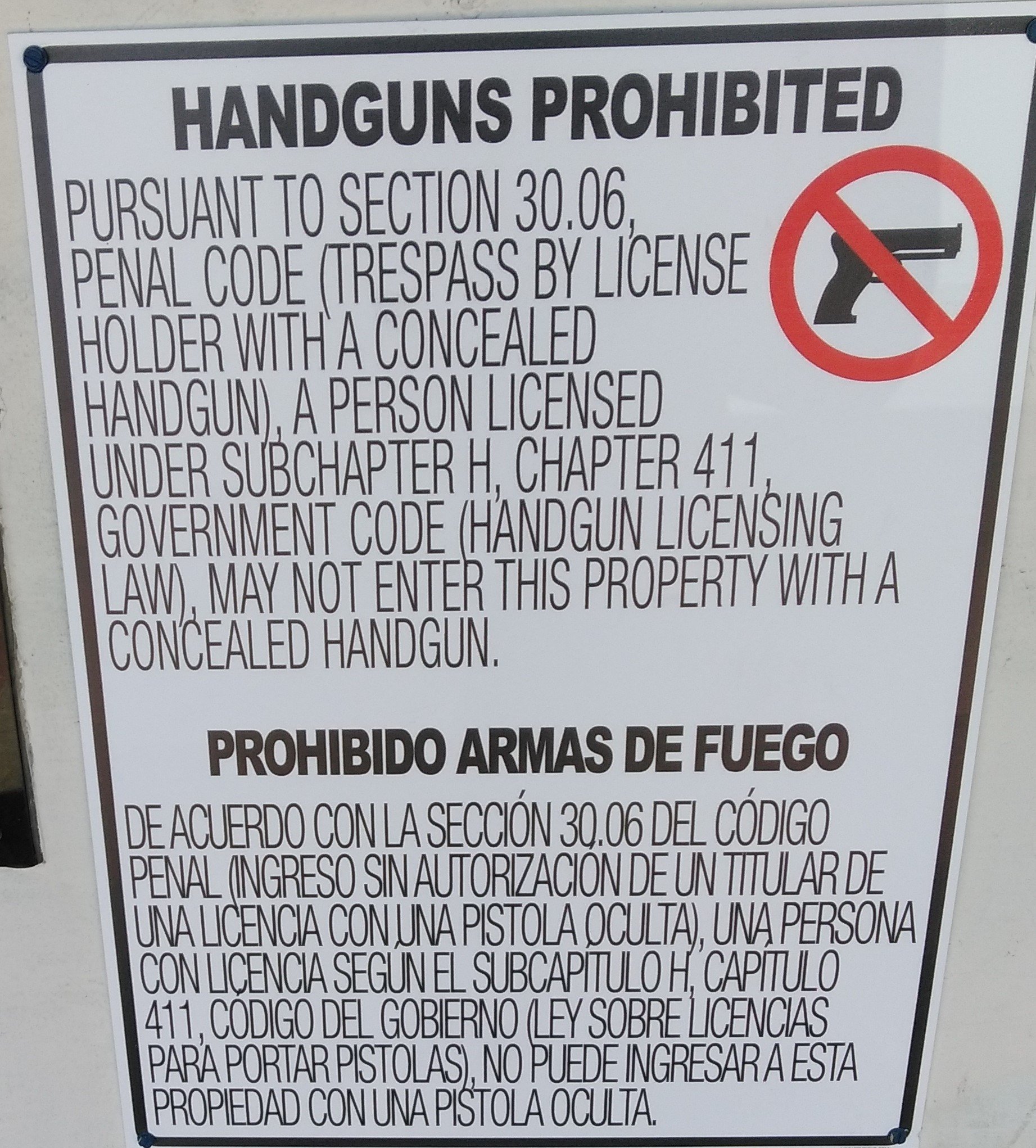

Across the seven campuses of the Dallas Community College District, more than $20,000 worth of signs blare "HANDGUNS PROHIBITED" in red, black and white. There is a sign on the Dr. Wright L. Lassiter Jr. Early College High School and the Cedar Valley Vet Tech Facility; there are signs dotting health centers on all seven campuses, including North Lake; there are signs prohibiting guns in laboratories, in daycare centers, at sports events; on certain days, like high school graduations or elections, auditoriums and polling places on campus will post new signs, informing attendees that guns are temporarily prohibited.

Community colleges have been given a strong model for navigating campus carry — including exemption guidelines that helped them decide where all these signs should be placed. But two-year schools also face challenges all their own.

One is the sheer numbers. There are more than 700,000 students enrolled at Texas community colleges. The Houston College Community District alone enrolls 114,000 students — more than the combined populations of Texas A&M and UT-Austin, roughly the size of the city of Round Rock.

Community college student populations skew both younger and older than those of four-year schools, and they include more part-time learners. Many community colleges have on their campus at least one early-college high school, a full-service institution whose students enroll in college courses. At South Texas College, for example, a full 42 percent of pupils are 18 years old or younger.

At most schools, guns will be banned in classes made up exclusively of minors, but not in classrooms that have some high schoolers. Daycare centers, another common presence on community college campuses, are also exempted areas.

The age issue swings the other way as well. Nationally, about half of community college students are over 21.

“Our average population is old enough to carry,” Dallas County Community College District Police Commissioner Lauretta Hill said. That brings with it obvious complications.

Then there are the quirky questions, like hands-on workforce training. Should students be allowed to carry a concealed weapon while working under a car, Austin Community College District administrators wondered, or while repairing a roof? For the most part, guns are prohibited in these areas, administrators said.

There is also at play an important question of mission. Open enrollment schools are accessible in more than symbolic ways, said Kimberly Beatty, an administrator at the Houston Community College District.

Hill — who has tried to remain neutral on the policy while implementing it on the seven campuses she oversees — has had a unique challenge: the memory of a sweet 20-year-old shot dead at school not three full months ago. The tragedy that took Gonzalez’s life, Hill says, “just increases people’s anxieties.”

“License to carry had not been instituted on campuses, and this student just came onto the campus,” she said. “You just never know if and when something like that can happen, having a law that allows you to carry or not having a law ... Those things can potentially happen on our campuses.”

Disclosure: San Jacinto College, Texas A&M University, Texas Tech University, Sam Houston State University, the Texas State University System, the University of Texas at Austin, UT Southwestern, Houston Community College and Austin Community College District have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/platoff-emma.JPG)