After Death at a Texas Psychiatric Hospital, Family Kept in the Dark

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/08/01/Keith-Photo-WithDocuments.jpg)

Shortly before noon on April 14, 2014, while their adult son slept in the next room, Anna and Daywood Clayton decided to call the police.

It was not a spur-of-the-moment decision for the elderly couple from Borger, Texas. They had agonized for days over what to do about 55-year-old Keith Clayton, who was hallucinating, talking about suicide and showing symptoms of schizophrenia.

They had asked a local judge how to get their son hospitalized. And they had called their 28-year-old granddaughter Samantha Clayton in San Antonio to ask for her blessing to send her father to one of Texas' state-run psychiatric hospitals. Having Keith Clayton committed seemed the best option to his parents, who were approaching their 80s and felt ill-equipped to care for a grown man with a serious mental illness and a history of alcoholism.

"We knew he needed help," Anna Clayton would later tell a police detective. "We just had no other choice."

It was an unseasonably cold day when the officers arrived; a light snow sprinkled the high plains of Texas Panhandle country. Daywood Clayton recalled trying to get his son, before he was handcuffed by the officers and loaded into their car, to put on a sweater.

It would be their final interaction.

Four days later, Keith Clayton was pronounced dead in an emergency room. He had stopped breathing after employees at the North Texas State Hospital in Wichita Falls forcibly restrained him for allegedly picking a fight. An autopsy found he died of a ruptured spleen caused by blunt trauma to the abdomen. He suffered internal bleeding and several fractured ribs.

It took five months for a medical examiner to rule the death an accident.

What happened during Keith Clayton's short stay at the psychiatric hospital hundreds of miles from home is still a mystery to his family members, who say the state has refused to give them an explanation. Anna Clayton said she didn't even know state hospital employees were involved in her stepson's death until a Texas Tribune reporter called her last month. For two years, she said, she'd been told he died in a "scuffle."

"We didn't have any idea if it was a patient that did it, or if it was a staff member, or not," she said. "They wouldn't tell us what happened. They wouldn't tell us anything."

Asked why Keith Clayton's family wasn't given complete information on his death, officials from the state hospital directed questions to their parent agency, the Texas Department of State Health Services. Officials there said they could not discuss specifics of the hospital's dealings with the family.

Keith Clayton's death is an example of the sometimes-fatal effects of restraints used to subdue patients at Texas' state-run facilities for people with mental illness — institutions that face an uncertain future due to unpredictable funding, crumbling infrastructure and a growing demand to house patients from an overcrowded criminal justice system. At a time when the state claims to be reducing its reliance on forcible restraints, Keith Clayton's case raises questions about the secrecy around such incidents, particularly when they end in death.

Keith Clayton's parents, daughter and stepsister said they wrote letters and made dozens of phone calls to state hospital administrators and other officials in the year after his death. At every turn, they said, they were told the information they sought was secret.

For Samantha Clayton, this was particularly hard to stomach. Despite her father's struggles with alcohol, he had been in good physical shape, she said, roller-blading for long distances and doing manual labor for his job at a trucking company. "Him just dropping down and dying, it just doesn't make sense," she said.

Keith Clayton was cremated. His family held a memorial in Borger. Two years passed. Anna Clayton, now 86, said the family eventually gave up on trying to discover the circumstances of his death.

"After a while, at our age, we're just not able to keep it going," she said.

The "Scuffle"

The Claytons weren't the only ones who struggled to get information on their son's death.

Over the course of six months, representatives for the North Texas State Hospital and the Department of State Health Services repeatedly declined to answer the Tribune's questions about the incident.

The health department originally refused to say which employees were involved in restraining Keith Clayton. When the Tribune obtained a list of employees who witnessed the restraint and presented it to the state health department, officials said it would cost more than $400 to provide information about those employees. The department later waived those fees but said it was unable to produce much of the material in time for this story's publication.

Department officials said privacy laws prohibited them from discussing individual patients, even though the patient was deceased. They eventually released documents describing a state investigation into two employees who restrained Keith Clayton, an investigation that appeared to be closed.

When pressed, department spokeswoman Christine Mann wrote in an email that there was "no additional releasable information" on Keith Clayton's death — "No police report or video footage."

The Tribune nonetheless obtained several police reports that provide a partial narrative of the events surrounding his death.

Keith Clayton arrived at the North Texas State Hospital after a five-hour drive from Borger, according to those documents, many of which are based on interviews with hospital staff. His arrival and the initial three days of his stay were, by all accounts, without incident.

State hospital staff told police he was a friendly, cooperative patient, a message they had relayed to his parents as well.

"They called us on Tuesday, said he was doing fine," Anna Clayton said in a recent telephone interview. "Called us Wednesday, said he was doing fine."

News of her son's death was sudden and jarring.

"Friday," she recalled, "they called us and said he was dead."

Around 3 p.m. that Friday, state hospital staff had gathered for a routine meeting to discuss patient developments.

The meeting was interrupted when Chelsea Mote, a psychiatric nursing assistant, came running. She said another assistant, Oscar Tinoco, had subdued Keith Clayton on the floor of a hallway near the elevator. A second employee, James Roy, joined in the restraint, later telling police he tried to help Tinoco by lying across the patient's legs to prevent him from kicking.

Staff rushed to the scene, where they saw blood on the floor and on Keith Clayton's forehead.

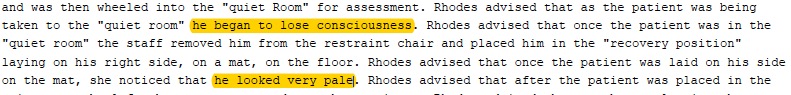

Police interviewed Tinoco and Roy five days later. When they did, Tinoco told them Clayton had come up behind him and punched him in the back of the head while he was supervising another patient. Tinoco said he tried to calm Clayton down but that the 55-year-old kept telling him he wanted to fight. Tinoco said he maneuvered around the 150-lb. Clayton, grabbing him from behind in a bear hug-like move and bringing him down to the floor, where he "applied pressure to his shoulders" for roughly five minutes, according to the police report. From there, hospital staff strapped Clayton into a restraint chair and wheeled him to a "quiet room."

At 235 lbs. and 280 lbs. respectively, Tinoco and Roy were a combined 365 lbs. heavier than Clayton, according to police records.

Roy told police Clayton had been verbally combative and was cussing at state hospital staff during the restraint. A different employee, Hershel Tubbs, added that Clayton had made "gurgling" noises.

In the quiet room, nurses said they noticed Clayton had lost consciousness and turned pale. They gave him oxygen and called an ambulance. When first responders arrived, they gave Clayton CPR before taking him to the emergency room. Clayton was pronounced dead at 4:30 p.m., roughly 90 minutes after he was first restrained.

Multiple state hospital employees told police they were briefed at the staff meeting that Clayton's behavior that morning had been erratic. They said Clayton had tried to escape by climbing into the crawl space above the ceiling. Staff did not record the attempted escape in an unusual-incident report that state hospital administrators typically fill out when a patient tries to flee because, the health department said, it "didn't rise to the level of requiring a formal report."

Missing Information

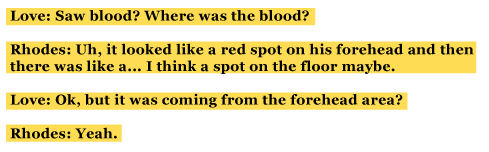

The day after Clayton's death, Brad Love, a detective for the Wichita Falls Police Department, attended his autopsy. From the medical examiner's office, Love wrote in his police report that Clayton's ribs were likely broken when emergency medical staff performed CPR. Two months later, in June, the medical examiner's report found that Clayton's internal injuries were "inconsistent with resuscitative efforts."

Love updated his police report on June 23, 2014, to note that the medical examiner, Susan Roe, had written him to say she was unable to determine if the death was accidental. Crucial information about the circumstances of Clayton's death, she wrote, "was requested and not received."

More than two months after that, on Sept. 8, 2014, Love updated the report once more to say the medical examiner still could not determine the cause of Clayton's death because of missing information. Love wrote in his report that he had already emailed Roe with the information he thought she needed, but he said he would send a second email that included documents produced by the state hospital and the transcripts of his interviews. A spokeswoman for the city of Wichita Falls provided Love's interview transcripts to the Tribune but said she could not locate the other documents.

Two weeks later, and five months after it occurred, the medical examiner ruled Clayton's death an accident.

Love, citing the autopsy, wrote in his final update to the police report that cirrhosis of the liver, a complication from alcoholism, had enlarged Clayton's spleen, which ruptured when hospital staff restrained him. Love found there was "no evidence to suggest that state hospital employees intentionally injured" Clayton.

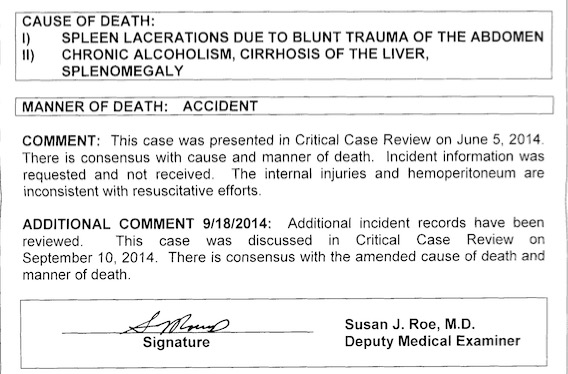

"I recommend this case be closed / cleared as an accidental death," Love wrote.

By that time, Tinoco had left the state hospital and was working at a nearby factory. In one of his final job performance reviews, less than three months after Clayton's death, a supervisor at the state hospital wrote that Tinoco "has good verbal communication to help promote prevention of restraint and seclusion."

In a brief telephone interview, Tinoco said he resigned his state hospital job of his own accord and that it was unrelated to Clayton's death. He said he was not pressured to leave.

Tinoco declined to discuss the restraint used on Clayton or the events leading up to his death. "I really don't feel comfortable just talking to you over the phone about something that happened two years ago," he said.

A Delayed Punishment

Though there would be no criminal charges, the state was quietly pursuing its own review of Clayton's death.

Investigators from Adult Protective Services, a state agency that looks into possible mistreatment of adults with disabilities, set out to determine if the restraint used on Clayton was tantamount to abuse. What resulted was a lengthy back-and-forth between investigators and the state hospital, spanning four rounds of reviews in which the hospital vigorously defended its staff.

Ultimately, one employee was fired. Roy, the psychiatric nursing assistant who helped restrain Clayton's legs, received a disciplinary letter on Aug. 18, 2015, one year and four months after Clayton's death. Adult Protective Services investigators determined that Roy had committed "Class I Physical Abuse."

State hospital policy requires that restraints be "implemented in such a way as to protect the health and safety of patients while preserving their dignity, rights and wellbeing." Restraints may not obstruct a patient's breathing or put pressure on the patient's torso.

"Since you were positioned securing the patient's feet in the restraint ... you were responsible for notifying the other employee involved in the restraint the patient was in a prone position and to reposition the patient into a side-lying position," Roy's supervisors wrote in his termination letter.

Roy, reached by telephone, declined to discuss the letter or Clayton's death.

But amid the state's investigation, James Smith, the superintendent of the North Texas State Hospital, offered a spirited defense of Roy and his colleagues, saying he disagreed with the findings and had doubts about the "objectivity" of the Adult Protective Services review.

In a January 2015 letter to David Lakey, then the head of the state health department, Smith said he had asked James Baker, the department's medical director for behavioral health, to review the case. Smith quoted Baker as saying that a patient with a medical history like Clayton's could have a particularly delicate spleen, "like an overfilled balloon ready to burst at the slightest touch."

"A relatively minor trauma — even the physical intervention of a perfectly-performed restraint — can lead to rupture," Smith quoted Baker as saying.

The state health department turned those letters over to the Tribune last week, six months after a reporter first began asking about the incident and three months after officials said there was "no additional releasable information." The documents appear to represent a small fraction of the records state investigators compiled during their review of Clayton's death.

Unusual state hospital incidents, even those involving death, are often shrouded in secrecy because health care laws are meant to protect sensitive medical information from misuse. The federal patient privacy law known as HIPAA applies to patients for 50 years after their death. Marty Cirkiel, a lawyer with experience in abuse and neglect cases at state hospitals, said that while state health officials must conduct a "root cause analysis" of deaths at state hospitals, those reports often do not become public without litigation.

"You really need somebody to file a lawsuit," he said. "That's the only way."

State hospital policy also does not require an autopsy for every death on campus. At the North Texas State Hospital, another patient, a 46-year-old black woman, died in March 2014 — one month before Clayton — after collapsing in the dining area, state records show. County officials said they could not locate an autopsy report matching the description of the patient, whose identity is unknown. Mann, the state spokeswoman, declined to say whether an autopsy was performed in that case.

For Clayton's family, confusion still reigns. They were never told that a hospital employee had been fired over Keith's death, and they didn't know many of the details of the investigations until the Tribune obtained the records.

Samantha Clayton said she struggles daily with the guilt of agreeing to have her father committed to an institution.

"I believe they killed him," she said.

And Keith Clayton's own elderly father still grapples with the loss of his only surviving biological child. His first wife and two daughters were killed in a car crash more than four decades ago.

Recalling his son being taken, in handcuffs, to a hospital where he was meant to be healed, Daywood Clayton said, "That was the last we ever seen him."

If you have experience with or information about the Texas state hospital system, email ewalters@texastribune.org.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Edgar_GpkYiWm.jpg)