In Cellphone Contraband Cases, Few Face Charges

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2014/05/02/TexTrib-CONTRABAND-001-Investigates.jpg)

Armed with shovels, correctional officers at a prison in East Texas last summer unearthed a cache filled with hundreds of smuggled items, including 45 cellphones and 52 chargers. Nearly a year later, no arrests have been made in the elaborate trafficking attempt.

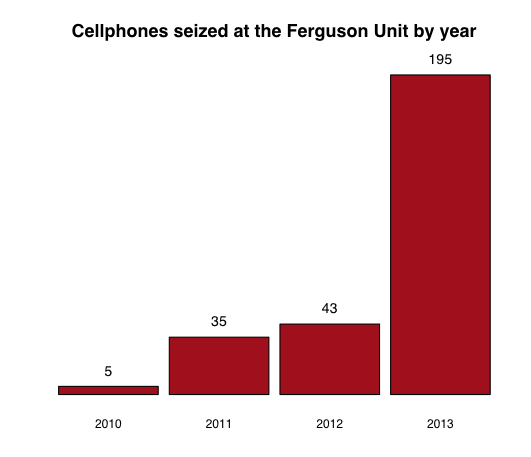

The discovery of buried items at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Ferguson Unit in Midway was unusual for its scale and its subterranean location, but the fact that no one was prosecuted is not.

A Texas Tribune investigation has found that few inmates or correctional officers face legal consequences for smuggling cellphones even as prison officials have intensified efforts to keep the devices out of prisons. Just 5 percent of cellphone smuggling cases investigated by the Criminal Justice Department’s Office of Inspector General from 2009 to 2013 resulted in a criminal sentence, according to documents obtained from the office through a public information request.

Prison officials said one challenge was linking the smuggled phones to prisoners or correctional officers for prosecution, because the devices were secreted away in spots that were hard to find, or found in common areas. And it falls to prosecutors in the rural, cash-strapped regions where prisons are typically located to decide whether to spend resources on criminals who are already in prison or on local law enforcement officers. Critics say that without serious consequences, there is little to stanch the flow of illicit cellphones — and the cash that goes with them — into Texas prisons.

“Phones can be hard to find, and there’s a lot of money in introducing contraband,” said Terry Pelz, a prison consultant and former warden who advocates tougher punishments for guards caught with contraband.

Texas’ criminal justice system, the nation’s largest, has invested heavily in efforts to keep cellphones out of prisons, where they have enabled inmates to coordinate escapes and maintain contact with gangs. In 2003, legislators made smuggling the devices into prisons a felony. Since 2009, the state has allocated $10 million every two years for “security enhancements for contraband interdiction,” said Robert Hurst, a Criminal Justice Department spokesman.

The enhancements include a special K-9 unit responsible for sniffing out cellphones, increased video surveillance of guards and the addition of “managed access systems” at two prisons that intercept all but a few specified outgoing cellular signals.

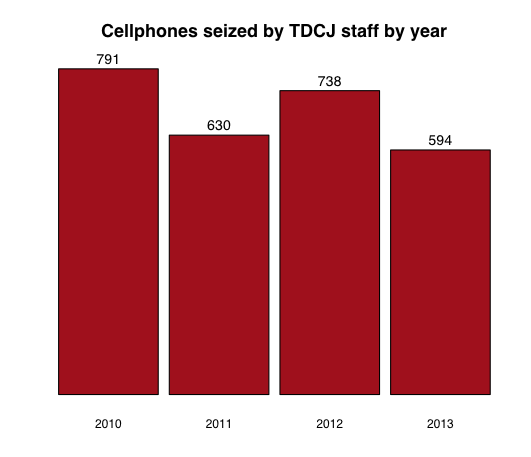

The increased emphasis, corrections officials and state legislators say, has had an effect. Cellphone confiscations by the Criminal Justice Department fell to 594 in 2013 — a five-year low — from 738 the previous year.

The buried loot at the Ferguson Unit was the largest of several “significant” contraband discoveries last year at the prison, which accounted for 34 percent of all cellphone confiscations among the state’s more than 100 prisons.

Records obtained by the Tribune show that cellphones accounted for the greatest number of contraband cases investigated by the Criminal Justice Department’s inspector general from 2009 to 2013. Yet cases involving other contraband — like alcohol and tobacco — are prosecuted at a higher rate.

Of the 3,687 cellphone cases the inspector general’s office examined during that time, prosecutors secured sentences in only 190 cases; 2,142 resulted in no charge. Criminal Justice Department officials said cellphones like those discovered in the pit at Ferguson often cannot be traced to a specific offender.

When an inmate is caught with contraband, the department can issue an “administrative” punishment or the case may be “informally resolved,” said Jason Clark, a department spokesman. The department’s inspector general investigates each case and presents the findings to a local prosecutor, who must decide whether to press charges.

Some criminal justice observers say leaving that decision to local prosecutors benefits the guards because prisons are typically in rural counties with small prosecution budgets.

“Local prosecutors don’t put the full force of their office up against cases involving officers,” said Brian McGiverin, a prisoners’ rights attorney for the Texas Civil Rights Project.

Pelz added, “These smaller counties don’t necessarily have the money for the wholesale prosecution of these officers, so that’s not much of a deterrent for those who get caught.”

Inmates have devised “ingenious” ways to sneak phones into prison, said William Stephens, director of the criminal justice department’s correctional institutions division, including hiding them in tractor tires, printers and various body cavities. In 2008, a death row inmate used a contraband cellphone to make a threatening call to state Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, prompting a statewide prison lockdown to search for cellphones.

Another appeal of contraband cellphones, criminal justice observers said, is that they allow inmates to circumvent the state’s expensive offender telephone service to call friends and family. In the 2013 fiscal year, the state received $13.1 million from the telephone service contract, Clark said. The vendor that provides the phone service, Century Link, also provided the criminal justice department with its two managed access systems.

The costs of the offender telephone service are “so high, that’s one of the reasons why inmates turn to cellphones,” said Michele Deitch, a prisons expert at the University of Texas at Austin. “They really need the phone access, which promotes healthier families, but at those rates it becomes an incredible burden on the families.” A phone call with the service costs up to 26 cents per minute.

For guards, who risk their jobs and felony charges by dealing in contraband, the financial reward can be much larger than their salaries.

“The temptation is there, if there’s not a strong deterrent to misbehavior,” said Pelz, the former warden, adding that a smuggled cellphone can fetch up to $3,000. “Your weakest link is the employees bringing the contraband in.”

Lance Lowry, president of the Texas correctional employees local of the American Federation of State County and Municipal Emlpoyees union, said many who resort to smuggling were trying to supplement low wages. Entry-level correctional officers make about $29,000 a year. At that rate, one cellphone could amount to 10 percent of an officer’s annual salary.

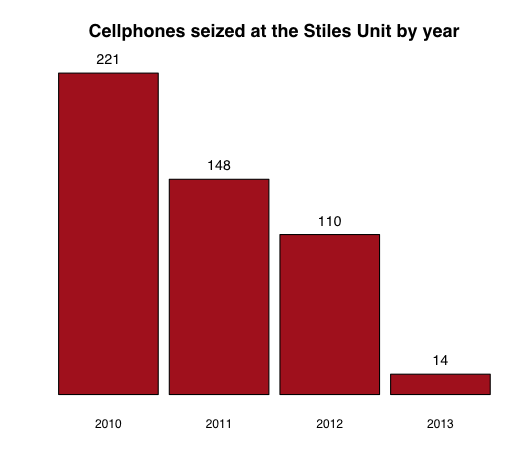

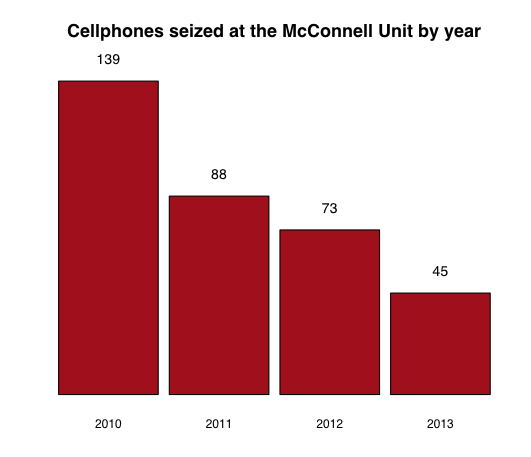

Though few cases end in prosecution, prison officials continue their efforts to intercept contraband phones. Reductions in confiscations at three prisons with historically high contraband rates accounted for much of the statewide decline in 2013.

Last year, the state shuttered a privately operated pre-parole facility in Mineral Wells. The unit was responsible for 17 percent of the state prison system’s total cellphone confiscations in 2012. At the Stiles and McConnell prison units, two of the state’s largest and most contraband-ridden, confiscations dropped nearly 90 percent and 40 percent, respectively, from 2012 to 2013.

Stephens said Texas’ prison system was doing better at curbing contraband than those in other states. In California last year, prison staff discovered more than 12,000 contraband cellphones. Still, he said, Texas could do more, because “one cellphone is too many.”

State Rep. Joe Moody, D-El Paso, said the state’s lawyers must make tough decisions about which cases to pursue. But the former prosecutor said cellphones “are a very serious charge,” and he added that “the reason lawmakers focused on it at such a high level is because that kind of contraband can be very dangerous.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin is a corporate sponsor of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Texas Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Edgar_GpkYiWm.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/0406_Dan_Keemahill_2x3.jpeg)