Guest Column: Pulling Young Texans Into Civic Life

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2013/06/03/Regina-Lawrence-photo.jpg)

During the fall of 2012, in the midst of a hard-fought presidential campaign, the Annette Strauss Institute convened several hundred Central Texans in Austin to discuss why young people often don’t “bother” to vote.

Some young people who attended were already actively engaged citizens; beyond voting, they were volunteering in their communities and trying to encourage their friends to vote. Others were disengaged: young people who had not yet stepped up to the civic duties many of their elders seem to take for granted. And in between were those who were involved in their communities or with social issues but who were not participating in traditional politics.

What we heard that evening was instructive. “How can I find my polling place easily?” one young woman asked. She described a frustrating 10-minute Google search that yielded no simple, straightforward directions on where to go to vote. (Happily, the Travis County clerk happened to be in the audience, and pledged to improve online information for voters.) This moment illustrates the informational challenge faced by inexperienced voters — young or old — when they first try to get involved.

Other challenges go deeper than information. “It seems like in politics, you have to be red or blue,” said a young man who described himself as active in his community but not in politics. “What if I don’t want to choose a team?” His question illustrates how politics can seem particularly uninviting to today’s young people — even those who are engaging in other ways in civic life.

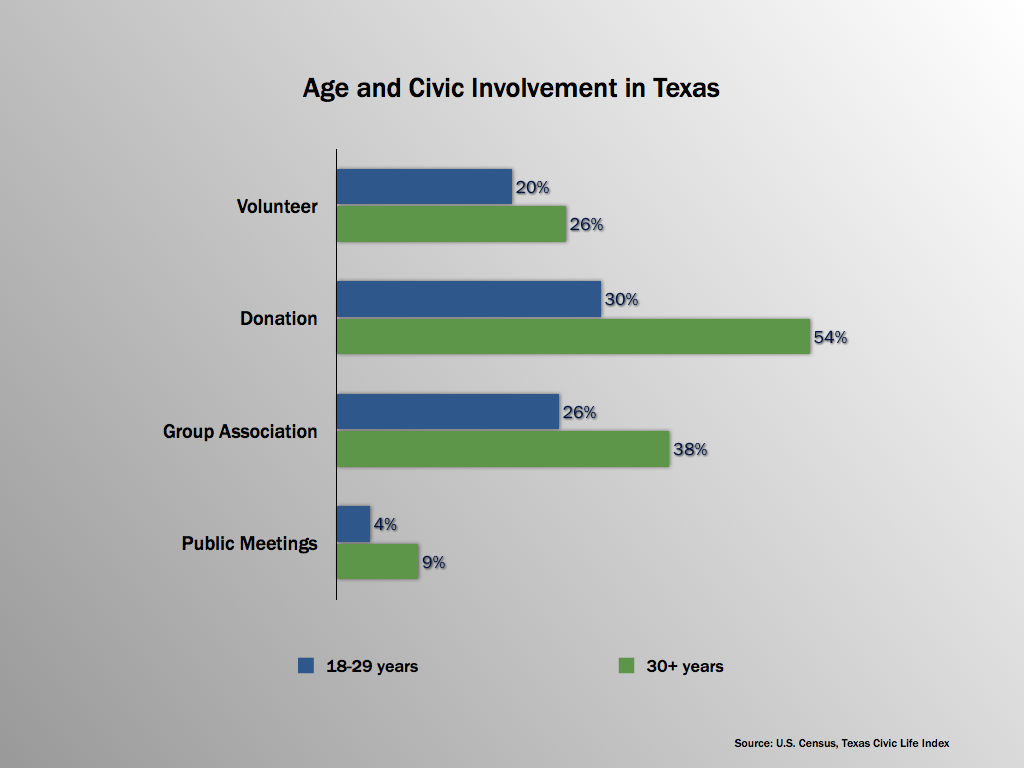

The evidence from the new Texas Civic Health Index, based on U.S. census data, is clear: Young Texans are significantly less engaged than older citizens in almost every aspect of political life. But the data — and our experiences with young people themselves — also suggest that many young people are involved in other ways, and that civic engagement can be nurtured more effectively.

First, let’s look at political participation. Voter registration is a gateway to greater political participation: Registered citizens are much more likely to engage in other ways as well, like contacting their elected officials. And of course, it’s the necessary first hurdle to actually voting. But only 43.1 percent of Texans between the ages of 18 and 29 were registered in 2010, compared with 67.4 percent of those 30 and older.

Voting rates in Texas are also strongly correlated with age. Only 30 percent of Texas’ young voters report that they voted in the 2012 election, versus 61 percent of those 30 and older. Low participation among the young is one reason that Texas trailed nearly every state in the country for voter turnout in 2012. In the 2010 midterm election, which brought many of our current state legislators into office, only 16.1 percent of younger citizens reported voting, versus 42.7 percent of citizens 30 and older.

At the same time, young Texans are not wholly disengaged. Two in 10 aged 18-29 volunteer for organizations, compared with 26.3 percent of those who are 30 and older. And among the youngest group queried by the census — 16- to 24-year-olds — 18.5 percent have volunteered. Unlike the gaping political participation divide between younger and older Texans, these data suggest a younger generation that is just about as involved in civic life as its elders. And the far less severe age gap in discussing politics is also noteworthy — as is the slight edge young people hold in expressing their opinions on the internet.

None of these rates is as high as we might want for a truly active citizenry. But these differences across forms of political and civic involvement urge us to consider what it is about politics that is not inviting to young people.

National data show several reasons why young people don’t vote. Interestingly, about 30 percent of young people nationally said they didn’t vote in 2010 because they were “too busy” — roughly the same percentage of Texans of all ages who said the same. Other reasons also stand out. For those in college, almost one-fourth said they were out of town or away from home — a significant hurdle for young people who have to figure out how to vote long distance when they don’t attend college in their hometowns or states. For those not attending college, the second-most frequently stated reason for not voting was that they “weren’t interested” or that they felt their vote “wouldn’t matter.”

How can these obstacles and attitudes be reversed?

Several particularly important approaches stand out for nurturing engagement among young people.

One is strengthening civics education in our schools. Research shows that students who receive high-quality civics education in school are more likely to vote and to discuss politics at home, more likely to volunteer and work on community issues, and are more confident in their ability to speak publicly and to communicate with their elected officials.

Texas is one of nine states that require both course completion and student assessment in civics. But while testing and assessment are important, the most effective approaches go further. Civics education needs to involve students in active learning that builds useful civic skills and creates a sense of civic attachment.

Another step is improving access to higher education. Better-educated Texans are more likely to vote; more likely to express their views to family, friends and elected officials; more likely to volunteer and join civic organizations; and more likely to work with others to address problems in their communities.

In part this is because education is associated with higher income, greater leisure time and greater self-esteem. Earning a college degree produces people with greater resources for civic participation. But even limited exposure to the college classroom is correlated with levels of engagement, suggesting that the college experience itself plays an important role in creating actively engaged citizens. This is no small concern for a state in which 20 percent of residents lack even a high school diploma, and another 26 percent have only that.

Another approach is building more opportunities for online participation — in which young people already have a slight edge. According to a recent national survey, online social networks are most heavily used by young people, and approximately 66 percent of social media users use these platforms to “post their thoughts about civic and political issues, react to others’ postings, press friends to act on issues and vote, [and] follow candidates.” Accordingly, one path to building more engaged citizenship runs through digital and social media.

Policy changes can also help. For example, same-day voter registration is correlated with higher voter turnout overall, and among young voters in particular. In 2008, according to CIRCLE, 59 percent of Americans aged 18-29 whose home states offered Election Day Registration voted — nine percentage points higher than those who did not live in EDR states.

Another vital factor is the introduction to civic life that young people receive at home. For example, adolescents who talk frequently about political affairs and current events with their parents score higher on measures of political knowledge and, when they enter young adulthood, tend to vote, volunteer and engage in civic activities more frequently than do youth who seldom discuss politics with their parents.

Finally, it is crucial that political officials and institutions do not treat the currently under-engaged as if they will always be so. As the recent Millennials Civic Health Index noted, “When political parties, civic associations, news organizations, and other institutions assume that young people do not engage, these institutions may avoid trying to recruit youth, which can lead to a cycle of disengagement.” The same can be said for other groups — Hispanics, African-Americans, immigrants and others — who could be assertively invited into the civic life of our state.

Regina Lawrence directs the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at UT-Austin, where she also serves on the faculty of the School of Journalism. The Texas Civic Health Index, a comprehensive summary of data from the U.S. Current Population Survey, is produced by the Annette Strauss Institute in partnership with the National Conference on Citizenship.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.