No Country For Health Care, Part 4: Rural Recruitment

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/010709_nocountry004.jpg)

PRESIDIO -- When doctors call Elva Torres about the opening at the remote Presidio County Medical Clinic, the first thing she does is send them a map. She rarely hears back.

“Somebody once told me, ‘Just don’t tell them how much you pay first,’” said Torres, the clinic administrator. “I told them, ‘I never even get that far!’”

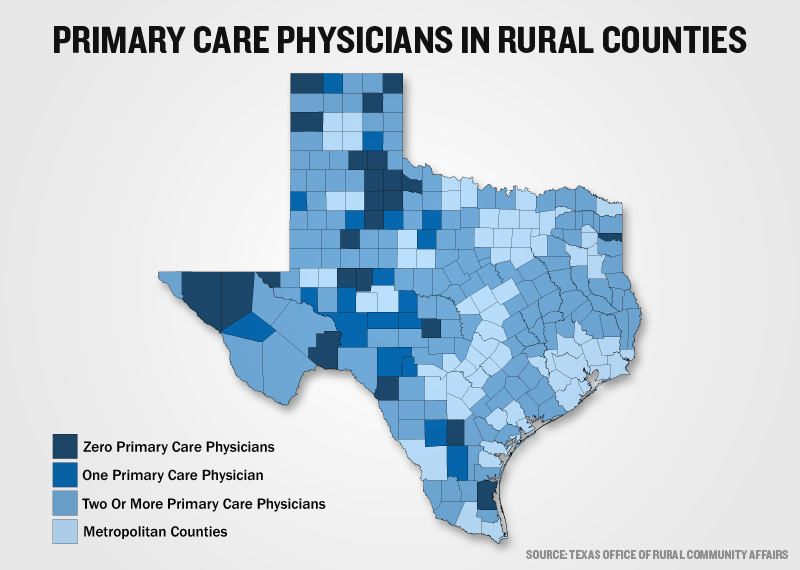

Across Texas’ rural counties, recruiting doctors is the single biggest health care challenge. Twenty-seven Texas counties have no primary care physicians; 16 have just one. An elderly doctor’s retirement is enough to shutter a rural hospital; a nurse practitioner’s relocation can send a community into crisis.

Much of the recruitment trouble is due to distance. The communities that need doctors are far from urban centers — and little luxuries like shopping malls and grocery stores. The salaries and loan repayment programs for young doctors who practice in underserved areas aren’t generous enough to make up for these inconveniences. Many rural patients are underinsured, chipping away from doctors’ profit margins.

“It’s easy for us to get out-recruited,” said Presidio County Judge Jerry Agan, an advocate for rural health care. “We’re an isolated area. Medical students who want their loans repaid can do it in Laredo or Del Rio — even El Paso — and live a better life.”

But some health care providers point to another hurdle: a state law that prohibits Texas hospitals from hiring doctors. They say the ban, which has been lifted in almost every other U.S. state, hinders recruitment. More and more, debt-strapped doctors are trading private practice for the ease and security of working for a hospital. The ban is particularly troublesome in rural Texas, advocates say, because there are so few established practices young doctors can join if they can’t afford to set up their own.

“To the younger doctors just out of medical school, and the older doctors nearing retirement, they don’t want to be responsible for the billing staff, the nursing staff,” said State Rep. Joe Heflin, D-Crosbyton, who endorsed a bill last legislative session that would’ve allowed rural hospitals to hire doctors. Gov. Rick Perry vetoed the measure, which was tacked onto legislation he opposed.

“They just want to do the job they were trained to do,” Heflin said.

Van Horn’s Culberson Hospital nearly closed five years ago, after the lone doctor who had served the community for five decades passed away. A private, Oklahoma-based health care company rescued the hospital, but Ladelle Bates, the facility’s administrator, said finding qualified staff is a constant challenge. Today, the hospital has two physicians and 14 nurses — most of whom live more than 100 miles away.

“You see a lot of interesting things out here, from rattlesnake bites to a horse rolling over you or a four-wheeler accident, or even getting kicked in the head by a cow or a goat,” Bates said. “But there’s the difficulty of not having a dry cleaners, not having grocery stores. There are a lot of differences from being in a metropolitan area.”

Dr. Darrell Parsons knows this firsthand. The Kansas native, who now practices in an impoverished three-county area in West Texas, said recruiting nurses, billers, medical assistants — even receptionists — is a nightmare. Couple that with low reimbursements from treating under-insured patients, and high travel time between remote clinics and hospitals, he said, and there are very few incentives to make the effort.

“The biggest challenge to practicing medicine out here is to keep your business viable, to keep your doors open,” Parsons said. “You’ve got to stay in the black. Doctors who can’t come and go all the time.”

For those that can stay in business, the workload is tremendous. They don’t have other doctors to share “call” with. They spend hours of their day figuring out where to refer patients to specialists — and then how to transport them to their appointments. Patients know where doctors live, and show up at their houses after hours.

Dr. Jim Luecke, a family practice doctor based in Alpine and Fort Davis, said on a typical day, he’ll drive 100 miles round trip to deliver a baby, perform a half dozen other medical procedures, and then make four hours of rounds in the Big Bend hospital’s emergency room.

When these patients can’t pay, rural doctors are often out of luck. Luecke said he’s been known to barter; he once traded an appendectomy for a truck engine, and a Caesarian section delivery for a lifetime of haircuts.

“Yes, it’s possible to make a living out here,” Luecke said. “It’s not as good as in the cities, but what you trade is the quality of life, the quality of the people.”

Dr. Weldon Green, who has spent the last 30 years practicing in rural Childress, said his living would’ve been far better if not for Texas’ “corporate practice of medicine” law, which bans hospitals from hiring doctors.

The law, which has long since been lifted in most other states, was designed to prevent hospitals from asserting improper influence over doctors and their treatment decisions. Opponents like Green say the measure harms doctors who want to work in rural communities, and can’t afford the overhead of private practice. Green has watched his revenue decline year after year, though his patient roster hasn’t dwindled.

Working for a hospital “would’ve allowed me to take care of patients and not have to worry with the business end of it,” said Green who, at 59, still works almost every day of the week — including one 24-hour shift at the local hospital. “Instead, I’ve ended up at the bottom of the barrel, with a lot less for retirement than I hoped.”

Proponents of the law, including the Texas Medical Association, say it still serves an important purpose. And they note there are already ample exceptions to it in Texas. Medical schools and federal health clinics can hire doctors. So can non-profit health care corporations — cooperatives of doctors that can be established for almost any hospital, including those in rural Texas. Some rural Texas doctors even say lifting the law isn't necessary.

“There are deterrents to coming to work out here,” Dr. Parsons said, “but the [hospital hiring ban] isn’t one of them.”

But rural health care supporters say the non-profit cooperatives aren’t always feasible for small town doctors. They’re costly, they’re complicated, and it takes three physicians to start one, said Don McBeath, director of advocacy for the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals. That’s a luxury some rural communities don’t have.

“These days, doctors want a guarantee, a steady income. They don’t want to have to worry about the particulars,” Luecke said. “I think letting hospitals hire them, bring them in, set them up — it’s the way of the future.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)