An Escape with Few Takers

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/121709_stuckinschool_jv.jpg)

When a Texas public school fails, the students are allowed to transfer — to leave and seek their educations elsewhere. Yet more than a decade after that policy was enacted, then later strengthened at the federal level, only a tiny fraction of eligible students ever take advantage of it.

Two programs in Texas, one state, one federal, require persistently failing schools to allow students to transfer to better schools, either within that district or another one. But the effort has largely failed, for a host of complex reasons.

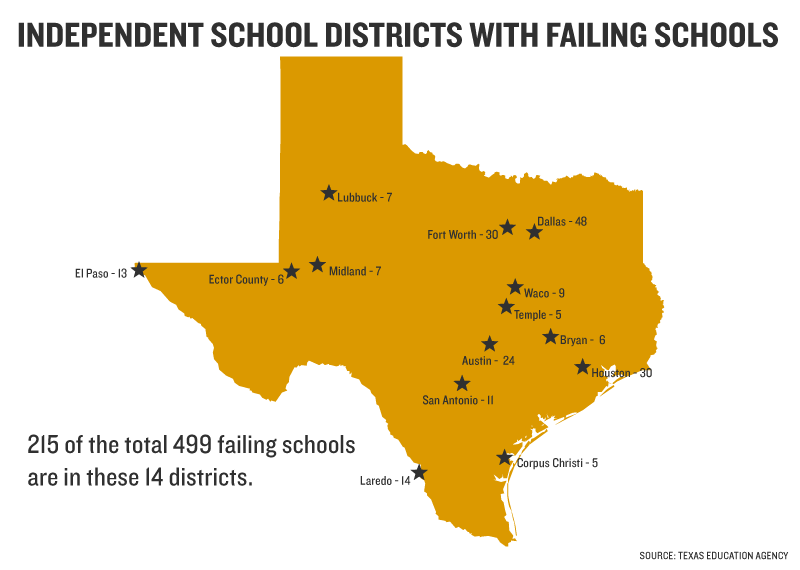

The state this week released its annual worst-schools list — 499 schools statewide, nearly half of them in its biggest cities — but the designation may matter little beyond wounding the pride of school faculties and district politicians. The state program, in particular, has problems that the Legislature has not addressed since its passage in 1995. Known as the Public Education Grant, or PEG program, the measure resulted in transfers of just 283 students out of a total of 437,064 who were eligible last year, according to Texas Education Agency data.

The failing schools list was dominated, not surprisingly, by campuses in impoverished urban and rural areas, with Dallas ISD having the highest number, at 48. The Houston and Fort Worth school districts each had 30 failing schools. Austin ISD had 24. Overall, just 15 school districts, out of more than 1,000 statewide, accounted for nearly half the total of failing campuses.

The exceedingly rare usage of transfer policies underscores the realities of school reform, particularly in impoverished settings: Educating the ever-escalating proportion of poor and minority students in Texas will largely depend on fixing the schools they already attend rather than devising escape routes. Even if the transfer policies were widely used, they raise vexing questions about what happens to the students remaining in failing schools after the “parents who are paying attention” withdraw their children and support, said Ed Fuller, director of research for the University Council for Educational Administration, housed by the University of Texas at Austin.

Historically, some transfer policies, enacted for a variety of reasons including desegregation, have benefitted individual families but left the schools they abandoned even worse off.

“As an individual parent, I want kids to be able to get out, to have a chance,” Fuller said. “But in terms of state or district policy, it just exacerbates the situation by creating dense concentrations of poor kids whose parents don’t transfer.”

The experience of Johnston High in East Austin provides a telling case study. The district allowed transfers long before the current state and federal policies, in the name of desegregation. And over time, many African American and Hispanic students left to attend majority white schools, including Austin High School. Those students tended to be stronger academically, as well as more able and interested in enduring longer commutes to schools where fewer students looked like them and shared their culture, said Austin ISD Board President Mark Williams.

Meanwhile, Johnston High lost able students and the money that financed them, including federal funds targeting special programs for poor students. Extra-curricular activities became harder to finance and populate at a smaller school with less-interested students. By the time the state stepped in and demanded the school be closed or overhauled, only about 700 of the 1,400 students in the school’s attendance zone chose Johnston.

Rather than close the school, Austin ISD officials worked with the state to overhaul the academic program and create an open enrollment campus, accessible to any students citywide. That way no student was forced to attend, Williams said, but any could choose to do so.

“The whole point behind closing the schools was so that kids wouldn’t be trapped there, but what I’ve had to tell people is that they already weren’t trapped there,” Williams said. “The ones who were there wanted to be there — we had already given them other opportunities.”

After the overhaul, many who might have been in the incoming freshman class did indeed choose other schools, largely because of the uncertainty about whether the school would be open at all. Most already in the school chose to stay, Williams said.

“I think on balance, those that left the school did better than those that stayed, but you have to look at who left,” he said. “Maybe the kids with the greatest needs aren’t the one who got on the bus and rode to Austin High School every day.”

The state transfer program had fatal weaknesses, including a provision allowing neighboring school systems to simply reject incoming students from failing schools, said TEA spokeswoman Debbie Ratcliffe. An even bigger factor: The state didn’t require districts to provide transportation.

“Because of that issue, when the Bush team went to Washington, they put in a requirement to provide transportation and cleaned up a lot of other issues,” Ratcliffe said.

But even with those changes, the federal effort to promote transfers from failing schools has hardly promoted a stampede of transfers. Now, when a failing school can’t make federally required “adequate yearly progress” toward improvement for two straight years, it must allow the transfers. The federal rules apply to a smaller but still large number of Texas campuses. This year, 355 schools fall under the federal transfer requirement, according to TEA data. TEA could not provide data Thursday on how many students at those schools qualified or how many had transferred this school year. But last year, just 2,193 transferred.

As for the state rules allowing transfers, TEA still must go through the motions of implementing the policy. But Ratcliffe concedes it has had little effect. Asked if the program still has reason to exist, she said: “A lot of people would say no.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt_bio_thevenot_brian.jpg)