The Conservative Core and the 2012 Primary Elections

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/f9f1bcf960942fbd3cd27294047dc306/BD%20INC%20CNN%20Debate%20Three%202012)

The February 2012 University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll added some dimension to our view of an obvious state of affairs: The prevailing currents in Texas politics remain deeply conservative. Of more consequence for the primary campaigns now under way: A strong riptide of intense, very conservative opinion is exerting a strong pull on state politics, particularly in statewide Republican Party primary contests. The most conservative of the conservative voting core in the state appear to be searching for a presidential candidate that is not Mitt Romney — a search that was evident back in the alternate universe of the October UT/Texas Tribune poll, where Herman Cain narrowly led the field along with Gov. Rick Perry.

The conservative core of the GOP electorate, however traditionally wedded to the Republican brand in general elections, also seems to be considering alternatives to established statewide officials in statewide contests. In contested state-level match-ups, conservatives appeared divided in their support for incumbents that GOP voters have kept in statewide offices for more than a decade, particularly given the presence of possible alternative candidates with plausible conservative credentials. What follows is a look at the snapshot of the GOP that the poll took of the Texas GOP’s preferences in the primary races as of February. The goal is not to predict or even handicap the outcomes of these races this far out from election day. As the national campaign continues to develop and Romney continues to leverage his financial resources, the numbers in Texas will continue to change. The goal here is to take a closer look at the intensely conservative group of voters who will play a decisive role on May 29 — and Nov. 2, for that matter.

Surface Churn: GOP Primary Electoral Contests

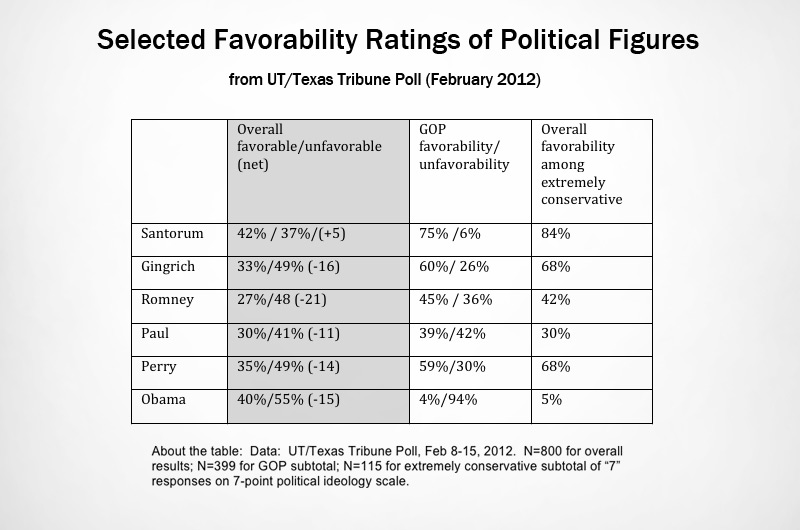

Mitt Romney’s favorability numbers in the February poll were strikingly mediocre, as the table below illustrates. (Perry and President Obama are included for comparative perspective.) Romney’s favorability ratings among all voters generated the highest net negative, -21, in the survey. He was in better stead among the GOP subsample, of course, though his favorable ratings are lower and his negatives higher than Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich. Among those who self-identify as “extremely conservative,” Romney is damned with faint praise, again running behind Santorum and Gingrich and, more ominously, considered “very favorably” by only 5 percent of the extremely conservative compared with Santorum’s 54 percent very favorable rating. (The relatively small number of “extremely conservative” responses (n=115) means that the specific results shouldn’t be taken too religiously — but even with a large margin of error, the difference between 5 percent and 54 percent tells you something.)

Primary contests expose and exacerbate intraparty fault lines. Volatile as these faults often appear, they should not obscure the extent of the broadly conservative orientation shared by a dominant plurality of Texas voters lodged in the Republican Party of Texas; however, they do bring into the foreground the dominance of a very conservative bloc of voters contained within that plurality.

The Very Conservative Core in Texas

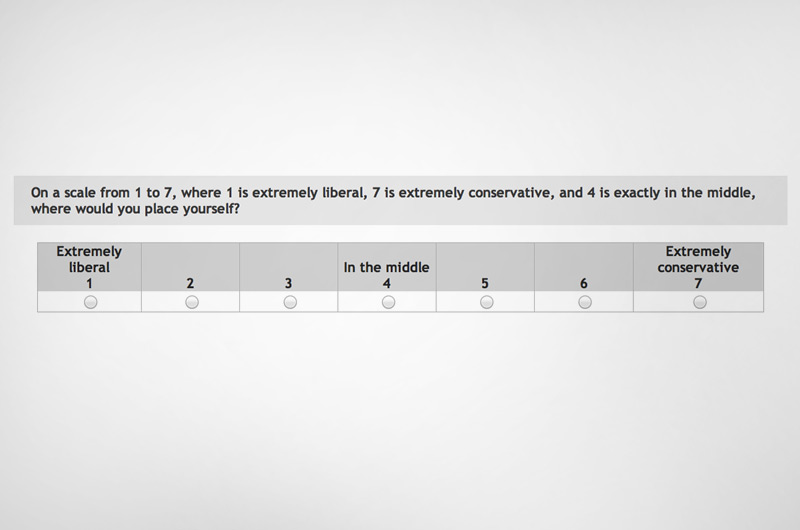

We can take a rough measure of the most conservative faction of conservatives in the Texas GOP by looking at those who identify with the most conservative self-rating on the 7-point “LIBCON” political ideology scale in which 1 is “extremely liberal” and 7 is “extremely conservative.” (The poll item used in data collection is pictured below.)

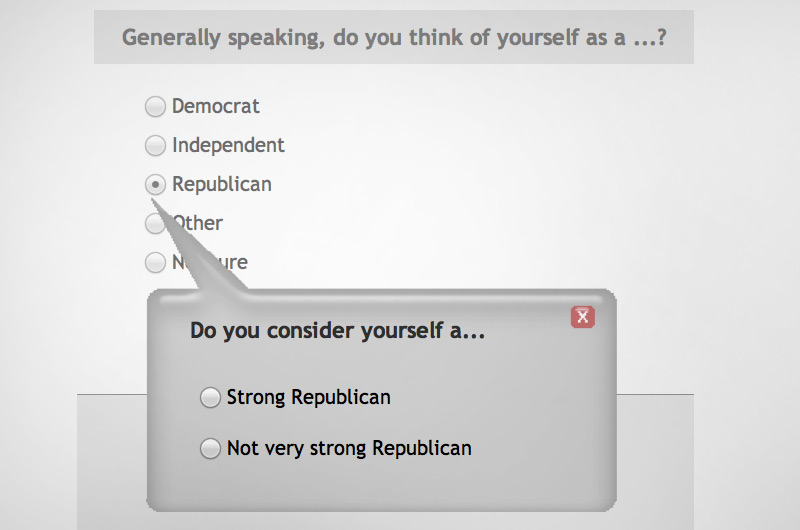

On the ideology scale, 14 percent of the overall sample identified as “extremely conservative” (7 on the scale); 92 percent of the “extremely conservative” identified as Republicans. Conversely, in the conventional 7-point party identification measure (which is presented differently, with a follow-up window, illustrated below), ranging from “strong Democrat” on the left to “strong Republican” on the right, 25 percent of Republicans identified as a 7 on the LIBCON scale. (As has been discussed elsewhere, those who identify themselves as independent leaners on the 7-point party identification scale tend to be more ideological than weak identifiers, and so are routinely counted as reliable voters for the party they lean toward. This means a distribution in the February poll of 42 percent Democrats, 8 percent “true” independents, and 49 percent Republicans.)

A rough estimate of the size of the block of the most conservative of conservative voters based on the February survey would fall between a floor of 14 percent (the extreme conservatives) and a ceiling made up of respondents to the two farthest right positions of the ideology scale, about 32 percent of registered voters and about 67 percent of the Republican Party identifiers.

This leads to a rough estimate of 25 percent to 30 percent of registered voters, as a plausible range of the size of the intense conservative core that is exerting a powerful gravitational pull on Texas politics. This allows for some of those in the “6” category to edge more toward the center than the right. About 25 percent of Republicans self-identify as extremely conservative, and as many as 67 percent perch on the ideologically conservative end of the party.

Given this range, even a low-end estimate suggests that the ideological extreme exerts a strong presence in the party primaries, a consideration of increasing interest given the lateness of this year’s primary and the very strong possibility of a low-turnout election — especially in runoffs — likely dominated by just this faction of the party. Of the self-identified extreme conservatives, 80 percent describe themselves as “extremely interested” — the highest percentage in any of the ideological categories (64 percent of the extreme liberals say the same); 82 percent of extreme conservatives say they vote in every, or almost every, election.

The Conservative Core and the GOP Primary

While the sheer magnitude of Santorum’s surge illustrated support across the board, he performed even better among extreme conservatives. Santorum improved ten percentage points among extreme conservatives at 65 percent, followed by Gingrich at 16 percent; both Romney (10 percent) and Paul (7 percent) dropped significantly. Largely because Santorum led by such a lopsided margin, there isn’t much difference between the expanded group of at least very conservative identifiers and the overall result.

The results of the GOP primary heats for the open U.S. Senate seat and for lieutenant governor are a bit more diffuse, but suggest conflicted support for nonestablishment candidates among the conservative core in both races. More so than the presidential results, with only sporadic advertising and limited media coverage and the delay in the primary elections, the lack of attention to those races means that public opinion is still tentative and not very well-formed.

But even with the elections months off (and in the case of the lieutenant governor’s race, years off), the results can tell us something about the attitudes of the conservative core of the GOP as the electoral system finally turns to a known election date.

In the U.S. Senate matchup, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst and former Solicitor General Ted Cruz split the extreme conservatives, taking 34 percent of the category each, with former Dallas Mayor Tom Leppert at 10 percent and former ESPN analyst Craig James at 7 percent. In the expanded category, Dewhurst leads Cruz slightly, 38 percent to 34 percent, with little movement for Leppert (7 percent) and James (8 percent). Cruz’s efforts to attract conservative GOP primary voters by focusing on conservative activists with the support of outside conservative groups such as the Club for Growth is making some inroads. Yet Dewhurst had not completely lost the very conservative bloc — his numbers compare very favorably to Romney’s support in the presidential race. While some might consider this damning with faint praise, Dewhurst clearly retains significant support.

A similar pattern exists in the results for the GOP 2014 nomination race for lieutenant governor, which at this point are highly speculative, but which still tell us something about where conservatives are at this point. State Comptroller Susan Combs and state Sen. Dan Patrick, R-Houston, the leaders in the field put before the sample, split the conservative vote in both the extreme conservative category and the expanded very conservative category with about 25 percent of the responses each. It is a safe bet that very few regular people are thinking about the 2014 election, and that responses for Combs and Patrick reflect the specific prominence each enjoys. Combs is a longtime statewide officeholder whose name is in the news (though not always positively in the last year or two). Patrick hosts a radio talk show host in a major media market in addition to being a state senator — half of his support came from the Houston area.

All of this qualification notwithstanding, when given the opportunity to register support, a quarter of the GOP primary voters chose Patrick, who uses his venues to brand himself as the conservative’s conservative and a champion of the Tea Party. That message seems to be getting through to conservatives.

Overall, chunks of very conservative voters did peel off in an identifiable if tentative pattern in which very conservative Republicans split their votes, largely between reasonably well-known statewide officeholders (Dewhurst and Combs) — think of them as “ins” — and less well-established candidates without the foundation of a statewide office but with specific means of touching intensely conservative constituencies (Cruz and Patrick) — think of them as “outs,” relatively speaking.

The outs are getting a look from a very conservative core of Texans now exerting a powerfully contradictory influence in Texas politics today. These voters have to be acknowledged as a regular feature of the political system, but their actual impact remains anything but predictable. They have provided bedrock support for the decadelong Republican hegemony over state government, but show a growing skepticism of the incumbents they helped become entrenched in office in the name of limited government. The odds-on bet at this point is that their loyalties remain sufficiently divided between establishment and insurgent candidates to avoid major upsets.

Odds notwithstanding, a very conservative fire burns inside the Republican Party. Perry rode its drafts to statewide victory in the 2010 primary, though it has already consumed the candidacies of a handful of Republican legislators and has set many if not most other GOP legislators running to stay ahead of it or at least get out of its path. The smart money may well be on the established candidates of the Republican establishment to persevere in 2012 and 2014. But in 2011, how much of that smart money placed bets that Rick Santorum would be a Texas frontrunner in February 2012?

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/henson-jim.jpg)