Crystal Mason's ballot was never counted. Will she still serve five years in prison for illegally voting?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/642ab6ae80513ba91aa94803dd0e15ca/05%20Crystal%20Mason%20LBS%20TT.jpg)

FORT WORTH — When Crystal Mason got out of federal prison, she said, she “got out running.”

By Nov. 8, 2016, when she’d been out for months but was still on supervised release, she was working full-time at Santander Bank in downtown Dallas and enrolled in night classes at Ogle Beauty School, trying, she said, to show her children that a “bump in the road doesn’t determine your future.”

On Election Day, there was yet another thing to do: After work, she drove through the rain to her polling place in the southern end of Tarrant County, expecting to vote for the first female president.

When she got there, she was surprised to learn that her name wasn’t on the roll. On the advice of a poll worker, she cast a provisional ballot instead. She didn’t make it to her night class.

A month later, she learned that her ballot had been rejected, and a few months after that, she was arrested. Because she was on supervised release, prosecutors argued, she had knowingly violated a law preventing felons from voting before completing their sentences. Mason insisted she had no idea officials considered her ineligible — and would never have risked her freedom if she had.

For “illegally voting,” she was sentenced to five years in prison. Now, as her lawyers attempt to persuade a Fort Worth appeals court to overturn that sentence, the question is whether she voted at all.

Created in 2002, provisional ballots were intended to serve as an electoral safe harbor, allowing a person to record her vote even amid questions about her eligibility. In 2016, more than 66,000 provisional ballots were cast in Texas, and the vast majority of those were rejected, most of them because they were cast by individuals who weren’t registered to vote, according to data compiled by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. In Tarrant County, where Mason lives, nearly 4,500 provisional ballots were cast that year, and 3,990 were rejected — but she was the only one who faced criminal prosecution.

In fact, Mason’s lawyer told a three-judge panel in North Texas last Tuesday, hers is the first known instance of an individual facing criminal charges for casting a ballot that ultimately didn’t count.

Her case, now pending before an all-Republican appeals panel, is about not just her freedom, but about the role and risks of the provisional ballot itself.

Prosecutors insist that they are not criminalizing individuals who merely vote by mistake. Despite those assurances, voting rights advocates fear the case could foster enough doubt among low-information voters that they’ll be discouraged from heading to the polls — or even clear a path for prosecutors to criminally pursue other provisional ballot-casters.

“There are a lot of people who have questions about whether they can vote or where they can vote,” said Andre Segura, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas. “You want all of those people to feel comfortable going in and submitting a provisional ballot.”

Mason, a highly private person who has been forced into the position of public example, has become a Rorschach test in the state’s fight over voting rights.

To her advocates, Mason is a victim of voter suppression in a state where, federal judges have ruled, GOP officials have a long history of infringing on the voting rights of people of color. To hawks intent on preserving the integrity of the ballot, Mason is a criminal who was caught before her crime could have an impact. To Mason, her story is one of countless missed opportunities, of a system she feels could have educated her at several critical points but instead has opted to make an example out of her.

“I feel like God has a purpose for everyone. Right now, I’m walking my purpose,” she said calmly in an interview the night before the hearing.

What is that purpose?

She smiled.

“I’m still trying to figure it out. Activist, I think — maybe educating on voting rights, your do’s and your don’ts,” she said.

“An untested application of the illegal voting statute”

When Congress created provisional ballots through the Help America Vote Act of 2002, it envisioned that prospective voters facing questions about their eligibility — either because of mistakes by local election officials or confusion about whether they are registered to vote — would not be turned away from the polls.

Federal law laid out a simple safeguard through provisional voting: If you’re not sure, cast a provisional ballot; if you’re not eligible, it won’t count in the election.

That was the procedure Mason followed in 2016, her lawyers argue, and that’s where her story should’ve ended.

In a courthouse in downtown Fort Worth, Thomas Buser-Clancy, a Texas attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, argued last week that Mason had made an honest mistake that ultimately had no impact on the election. How could it be, then, that she had “illegally voted”?

Arguing for the Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office, prosecutor Helena Faulkner countered that “nothing in the Texas Election Code indicates that the verb ‘to vote’ has to include or only includes a vote that was tallied in the final election.”

The law, she argued, should not protect those who intentionally vote illegally. But prosecutors would not use it to penalize those who make honest mistakes.

“People can make mistakes,” said Sam Jordan, a communications officer for the district attorney’s office. “The difference is in the intent.”

But who decides whether a ballot was an honest mistake?

Mason’s conviction hinged on an affidavit she had signed before casting her provisional ballot. At her trial, the judge convicted her of voting illegally after he heard testimony from a poll worker who said he had watched Mason read and run her finger along each line of an affidavit that required individuals to swear that “if a felon, I have completed all my punishment including any term of incarceration, parole, supervision, period of probation, or I have been pardoned.” Mason said she did not read that side of the paper.

Mason was still under supervised release for a federal conviction. She was indicted in 2011 for helping clients at her tax preparation business falsify expenses and claim exemptions they were not entitled to in order to lower their tax bills.

Her lawyers argue that the law is murky. Texas law allows convicted felons to vote once they’ve completed their “sentence,” including any “parole or supervision.” But it’s not clear that federal “supervised release” lines up with “supervision” under that law, Mason’s lawyers say.

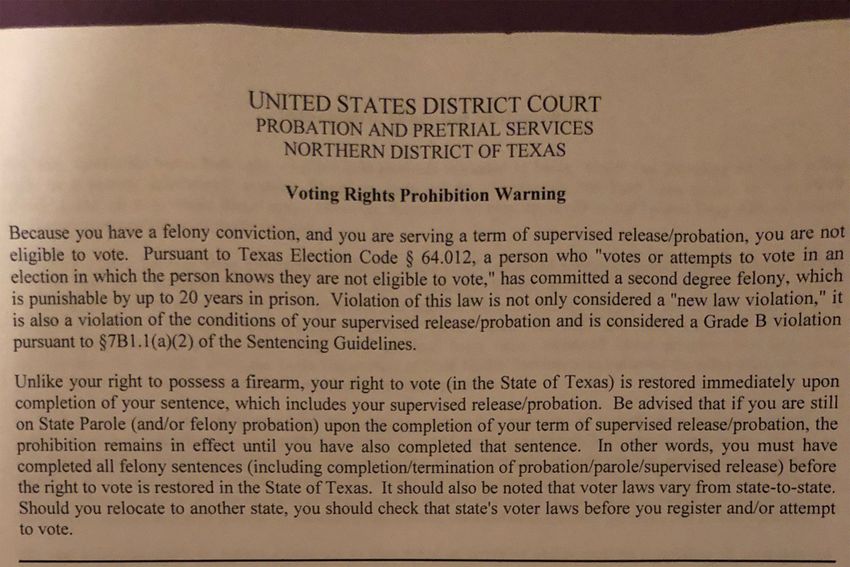

Since Mason’s case arose, she and her lawyers say, parole officers in North Texas have begun distributing a form to their charges clarifying that they are ineligible to vote while on supervised release. (Questions about the form to the Northern District of Texas, which oversees that system, went unanswered.)

The irony is not lost on Mason, who received that form after she was released this year. If it’s so unclear, she wondered, why wasn’t that notice being issued three years ago, when it might have helped her? And if it’s so ambiguous that clarification is required, why is she being prosecuted?

Mason likely could have secured a shorter sentence if she had pleaded guilty. But she didn’t want to admit to a crime she did not commit, she said. Still, the consequences were steep: The illegal voting conviction landed her back in federal prison for months, and she was released into a halfway house in May of this year. Last week, in addition to her high-stakes hearing, she was navigating her first week at a new job.

Her appeal turns instead on narrow legal questions — did a person vote (illegally or otherwise) if her vote didn’t count? — but the decision, expected in the coming months, will mark an important milestone in the state’s battle over the ballot.

Most provisional ballots are rejected for ineligibility; even those that are accepted are not usually counted unless an election is particularly close. But Mason’s advocates fear that her case could imperil the tens of thousands of other Texans who submit provisional ballots every election year.

“What we’re faced with here is criminalizing that behavior,” said Beth Stevens, voting rights program director at the Texas Civil Rights Project. “And the state’s interpretation of the illegal voting statute would necessarily make all of those people — thousands of people across the state of Texas — vulnerable to prosecution.”

As a mother and grandmother who raised her brother’s children as well as her own, Mason said she wouldn’t punish someone who did something wrong without intending to.

Instead, she’d educate: “You educate her on what to do, what not to do,” she said.

It was Mason’s mother who encouraged her to vote that day in 2016 — a message she has pushed since Mason was a little girl, and has spread, too, to Mason’s children.

“Ancestors fought for this right, marched and died for this right — now that it’s available for us, we should utilize it,” Mason recalled. “You can’t complain about anything if we don’t try to exercise that right.”

Before the hearing began, Mason’s pastor led her attorneys and a group of her family members, too many of them to fit in one elevator, in prayer outside the courtroom.

The case is “not just for Crystal, but mostly for justice,” said the Rev. Frederick Haynes of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas as the others stood, eyes closed, holding hands, in a circle.

“This is a form of voter suppression,” Haynes said.

“Safeguarding the integrity of our elections”

To those fighting on Mason’s behalf in court, the prosecution is “part and parcel” of a voter intimidation playbook that’s guided the state for more than a decade.

Gone are the days of “white primaries,” poll taxes and annual reregistration requirements enacted in the name of protecting the election process from voter fraud. The modern-day crackdown — fueled by unsubstantiated concerns over rampant illegal voting — led with a strict 2011 voter ID law that was softened after a federal judge expressed concerns that it disenfranchised voters of color.

Amid failed efforts to impose tighter voting restrictions and to scour the voter rolls for supposed noncitizens, attention has more recently turned to a handful of high-profile prosecutions of people of color.

Before Mason, who is black, there was Rosa Maria Ortega, a legal permanent resident also living in Tarrant County who was convicted of voter fraud after attempting to register to vote despite not being a citizen. Ortega — who did not realize her immigration status meant she was ineligible — cast ballots that counted in several elections.

When Ortega was sentenced to eight years in prison in 2017, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton — whose office did not respond to questions for this story — hailed it as an outcome that “sends a message that violators of the state’s election law will be prosecuted to the fullest.”

“Safeguarding the integrity of our elections is essential to preserving our democracy,” Paxton said in a statement at the time.

Tarrant County prosecutors have brushed off concerns the Mason case could lead to voter suppression. “The fact that this case is so unique should emphasize why this case should in no way have a ‘chilling effect’ on anyone except people who knowingly vote illegally,” Jordan said.

But during the 2019 legislative session, some Republican lawmakers pushed to erase Mason’s legal defense for future defendants by making it easier to prosecute people who cast ballots without realizing they’re ineligible.

Currently, to commit a crime, voters must know they are ineligible; under the proposed law, they would commit a crime just by voting while knowing about the circumstances that made them ineligible. In other words, Mason would have been illegally voting because she was aware of her past felony conviction — even if she was not aware her “supervised release” status made her ineligible.

The fact that Mason’s provisional ballot wasn’t actually counted would have also been ruled out as a legal defense under the proposed changes to state law. That legislation ultimately failed in the House amid major opposition from Democrats.

Mason’s appeal also comes in the wake of a bungled review of the voter rolls that did more harm than good to Republicans’ voter fraud crusade.

Texas leaders set out to scour the state’s massive voter registration database for supposed noncitizens, setting up nearly 100,000 registered voters to have to prove their citizenship to remain on the rolls. When the secretary of state’s office announced the review, Paxton used the development to boast about the numerous prosecutions his office’s Election Voter Fraud Unit was working on. (At the time, he was seeking additional dollars from state appropriators to expand the unit.)

But the review efforts were marred by shoddy data. Within days, it was revealed that the state had mistakenly marked tens of thousands of naturalized citizens as suspect voters.

When the Legislature wrapped up in late May, it did so without passing any of the major legislation that Texas Republicans, backed by the attorney general, had put forth as part of their voter fraud crackdown.

That leaves criminal prosecution as one of the most powerful tools state officials have for targeting what they have characterized as an epidemic of voter fraud.

Still, one high-profile criminal prosecution may be enough, advocates said.

“Crystal is the face of, ‘You should have been scared about going to vote, black people,’” said Jasmine Crockett, president of the Dallas Black Criminal Bar Association. “I don’t think there are more people that are going to end up being prosecuted unless there are too many black and brown people voting. I really believe that.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/platoff-emma.JPG)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/ura-alexa_TT.jpg)