State of Pay

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/StateTroopersMissing.jpg)

Sometimes Brian Hawthorne just shakes his head in wonderment. How is it that a campus cop can make more money than an officer in the legendary Texas Rangers?

“There’s a problem,” says Hawthorne, president of the Department of Public Safety Officers Association.

The Texas State Auditor’s Office put that problem in black and white last week with a review comparing state law enforcement salaries to those of local police in departments with more than 1,000 officers. For some positions, state pay lags nearly 20 percent behind local police pay. It would cost Texas nearly $50 million over two years to align maximum state police salaries with maximum local police salaries, according to the auditor's report — and it would take about $40 million just to get state police to the mid-range average salary for local police. “The Legislature may wish to consider revising [law enforcement salaries] to provide competitive salaries,” the report recommended.

Poor pay and strict training and promotion standards have contributed in no small part to a commissioned officer vacancy rate at the Department of Public Safety of about 10 percent. About 370 of the department's approximately 3,500 commissioned officer positions are vacant, says Jesse White, its chief human resources officer. DPS has amped up recruiting efforts and reworked some training and promotion policies to retain troops. Salaries, however, are out of its control. Lawmakers set the DPS budget and state employee salary schedules every two years. And with an estimated $18 billion budget shortfall ahead in the 2011 legislative session, they’ve already asked state agencies — including DPS — to cut back expenses. Despite the budget woes, at least some lawmakers say they must find ways to make trooper pay more competitive or jeopardize the quality of the state’s police force. “I just think it compromises public safety,” says state Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, chairman of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee.

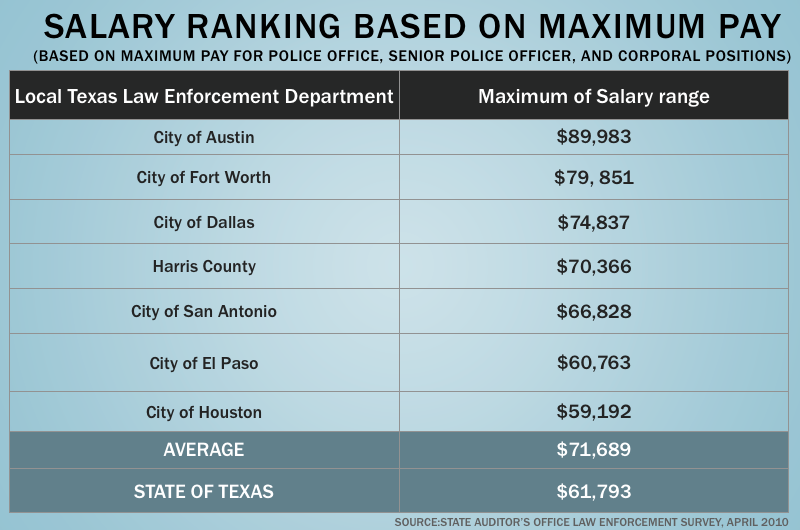

The state auditor’s review compared the salaries of state law enforcement officers in the DPS, the Parks and Wildlife Department, the Alcoholic Beverage Commission and the Department of Criminal Justice to police salaries in six metropolitan police departments — Austin, Dallas, El Paso, Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio — and the Harris County Sheriff's Office. State pay usually came up short.

The maximum state pay for experienced patrol officers is about $61,800. Among the seven big-city entities, only two paid less: El Paso and Houston. The city of Austin pays officers the highest salaries, approaching $90,000 at the top end. Even some university police forces pay more than DPS. The maximum pay for a University of Houston patrol officer is $69,000. To bring state patrol officers’ pay in line with the average maximum would require a 16 percent salary increase, according to the report.

For supervisors, including sergeants, lieutenants and captains, maximum pay for state officers was 14 to 20 percent lower than pay for local officers. Average maximum pay for captains in local departments was about $101,000 a year, compared to about $84,400 for DPS captains. A police captain at the University of Texas at El Paso can make up to $112,000.

Compared to salaries in some smaller rural police and sheriff’s departments, DPS pays fairly well, says Tom Gaylor, deputy executive director of the Texas Municipal Police Association. But when it comes to big, urban agencies, state trooper compensation doesn’t compare. “When I was a cop in Plano, we were working the same beat, basically … but they were making $20,000 less,” Gaylor says. Part of the problem, he says, is that the state takes a one-size-fits-all approach to law enforcement pay, setting one rate for all officers instead of adjusting salaries based on cost-of-living variations across Texas. “It’s a real disincentive for those guys to stay in metro areas or suburban areas, because the pay doesn’t go as far,” he says.

Another big advantage for local officers: They don't have to move to get a promotion. For many years, DPS troopers typically had to relocate from one area of the state to another to climb the ladder. But that’s one of the issues the department has worked to address internally, says spokeswoman Tela Mange. “A lot of people have spouses who have careers, who don’t necessarily want to pick up and move across the state,” she says. It used to be that some officers would move hours away from their families to work and then return home to visit on the weekends. Recognizing the strain that put on officers, Mange says, the department now works to give officers more say in where they are stationed.

DPS also has loosened training requirements for police officers from other agencies who want to become troopers. The department shortened its training school for already trained peace officers from six months to two months. And DPS has redoubled its recruiting efforts, focusing particularly on soldiers preparing to leave military duty. The department has its own recruiting website, www.joindps.com, has launched radio ads and soon will air a 30-second commercial during movie theater previews in Texas cities. “We’re making sure that the word is out there,” says Valerie Fulmer, assistant director of DPS’s administrative division.

The policy adjustments and the increased recruiting have helped, Mange says, but there’s not much DPS can do about salaries. The pay discrepancy isn’t a new phenomenon for DPS, which has asked lawmakers each session to narrow the gap. But every time the state raises state law enforcement compensation, local departments increase pay, too. “The training troopers receive is outstanding, and it really hurts when people leave and take that training with them,” Mange says.

Lawmakers’ ability to boost state cop pay may be limited next year, too. Gov. Rick Perry, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst and House Speaker Joe Straus have already asked state agencies to drop 10 percent from their budgets in the next biennium. Sen. Whitmire says DPS — which reported a $27.5 million budget hole in January — should be shielded from additional budget cuts. Instead, he says, lawmakers should improve trooper pay to make it more competitive with local departments. “DPS is a fine department, but it won’t be fine much longer if we don’t give them the resources and certainly the pay level needed to recruit and retain outstanding individuals,” he says.

DPS officials recognize they will be fighting for sparse dollars next year. They are used to coming up short in comparison to locals, they say. Officers don’t become state troopers for the money, Fulmer says; they do it because they believe in the agency’s mission. “Folks we get are folks who always wanted to be troopers,” she says.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)