The Getaway

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/DPSChase004.jpg)

On a quiet November morning, Johnny Hernandez patrols the dusty back roads along the Rio Grande in Hidalgo County. In the back seat, his M4 rifle sits within arm’s reach. In the trunk is a bulletproof vest. The 15-year Department of Public Safety trooper says he's been in so many high-speed pursuits that he can’t remember the first one — and, to be honest, he doesn’t even think in terms of which one was the scariest.

“There’s just so much” going on, he says. “Your thoughts are going 100 miles per hour.”

Often, so is his car.

Hernandez is one of about 60 DPS troopers in Hidalgo County who, together, logged far more high-speed chases between January 2005 and July 2010 than officers in any other region of the state, according to an analysis of nearly 5,000 DPS pursuit reports by The Texas Tribune and the San Antonio Express-News. Nearly 13 percent of the chases — 656 — happened in Hidalgo County. Of the 10 counties with the most chases, five were counties along the Texas-Mexico border.

For troopers who spend their days and nights patrolling the interstates, highways and meandering caliche roads of South Texas, the reason is simple. “We’re the first line of defense out here,” Hernandez says. “We’re going to have pursuits.” DPS troopers say smugglers are becoming more active and brazen, taking desperate measures to avoid being caught.

The analysis also reveals that troopers use aggressive pursuit tactics — including firing guns and setting up roadblocks — that many other law enforcement agencies prohibit. One expert says that DPS policies allow troopers to take too many risks, endangering the lives of officers and bystanders. “They’re crazy,” says Geoffrey Alpert, a professor at the University of South Carolina, who has studied pursuits at police departments across the country.

DPS officials and troopers say their training has improved in recent years and that safety is always their top priority. “We’ve got families, too, and we want to go home to them,” Hernandez says.

Eluding officers

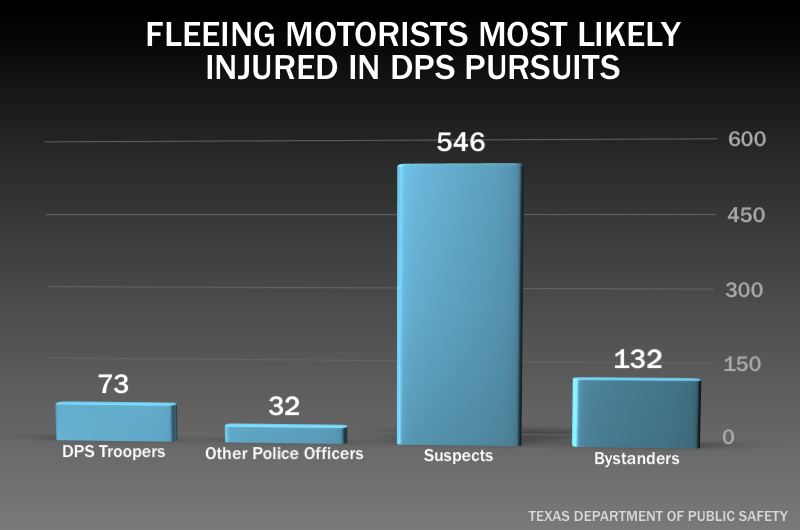

Statewide, DPS chases resulted in 1,300 accidents, 780 injuries to troopers, other officers, suspects and bystanders, 28 deaths and an estimated $8.4 million in property damage in the last five years. In Hidalgo County, the chases caused 71 injuries, two deaths and more than $440,000 in property damage.

Statewide, DPS chases resulted in 1,300 accidents, 780 injuries to troopers, other officers, suspects and bystanders, 28 deaths and an estimated $8.4 million in property damage in the last five years. In Hidalgo County, the chases caused 71 injuries, two deaths and more than $440,000 in property damage.

The pursuits didn’t always end with fleeing motorists in handcuffs, though. The suspects in about 40 percent of chases in Hidalgo County escaped on foot — or swam away to Mexico — eluding officers and often leaving behind loads of marijuana and narcotics in vehicles mangled in accidents and sometimes submerged in the Rio Grande. Statewide, more than 30 percent of all DPS chases ended with the suspect eluding officers on foot. Fewer than a quarter of all suspects, both statewide and in Hidalgo County, stopped and surrendered.

Despite the danger involved and the fact that so many suspects get away, Hernandez says, most pursuits are successful because they at least take off the market a few loads of drugs that would otherwise be sold on the streets or in schools. “We would love to arrest him and let him pay the consequences,” Hernandez says. “They know they can get over there [to Mexico], and we have no jurisdiction.”

New tactics

Troopers say smugglers are constantly developing new tactics to avoid arrest and get the drugs or humans they're hauling into Texas. In the last year, smugglers started using homemade spikes — bags full of nails welded together in a triangular shape — to blow out tires on patrol vehicles. They also take advantage of dirt roads in rural areas to kick up dust, reduce visibility and elude officers.“I’ve been doing this 23 years, and it still scares me,” says Sgt. James Davidson, who has been the lead officer on at least five chases in the last five years. “These guys have no regard for anybody’s safety.”

Trooper Chases Totals By County: Jan. 2005-July 2010

Source: Texas Department of Public Safety

Sometimes the suspects they chase don’t even have regard for their own lives. Last April, trooper Edwardo Ruiz was blazing down back roads in Hidalgo County at nearly 100 miles per hour, his patrol car’s siren blaring and lights flashing, in pursuit of a reckless driver in a black pickup. Suddenly the truck’s red taillights disappeared from view. Ruiz, filmed on the car’s dash camera, stopped where the road came to a dead end. “It looks like they grew wings and flew or something,” Ruiz said to another officer on his cell phone, as he peered into dark, empty fields. “He disappeared on me, man.”

Thirty minutes later, officers found the truck smashed into a canal on the other side of the dead end. The 18-year-old driver was dead inside. His blood-alcohol content was .22 — nearly three times the legal limit.

Troopers blame smugglers for the high number of pursuits on the border. But DPS has also beefed up patrols. Since 2006, DPS has assigned more than 160 additional troopers to the border. “We’re making it more difficult for the smugglers to move their products across and try to get them to the middle portion of the state,” says DPS spokeswoman Tela Mange.

Since 2007, lawmakers in Austin have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to beef up border security, including hiring more state troopers to patrol the region. About a decade ago, just 20 highway patrolmen worked in Hidalgo County, says Lt. Armando Garza, who supervises them. Now there are three times as many. Garza recently moved back to the border after working for 12 years in Corpus Christi, where, he says, troopers had one or two chases every three or four months. In Hidalgo County, it’s almost a daily occurrence. The peak was earlier this year, when there were six pursuits in two days — including one that ended when the suspect escaped from his car only to get pinned under a train that severed his arm.

“The only thing we can do is remind our [troopers] to be cautious, not to take any unwarranted risks,” Garza says.

"Loose" policies

DPS policies allow troopers to engage in riskier chase tactics than several other large Texas police and sheriffs’ departments. Troopers can set up rolling and stationary roadblocks to end a chase, a strategy they used 68 times from 2005 to 2009. Troopers also can shoot out a suspect’s tires if other methods, such as deploying spike strips, fail to stop the pursuit. Troopers fired their guns during chases nearly 90 times over the last five years, with 14 of those incidents occurring during pursuits in urban areas.

DPS policies allow troopers to engage in riskier chase tactics than several other large Texas police and sheriffs’ departments. Troopers can set up rolling and stationary roadblocks to end a chase, a strategy they used 68 times from 2005 to 2009. Troopers also can shoot out a suspect’s tires if other methods, such as deploying spike strips, fail to stop the pursuit. Troopers fired their guns during chases nearly 90 times over the last five years, with 14 of those incidents occurring during pursuits in urban areas.

By contrast, the San Antonio, Fort Worth and Austin police departments and the Harris County Sheriff’s Office prohibit officers from using their firearms during a pursuit except in self-defense or to defend others, and they are not allowed to set up roadblocks to stop a chase. The Houston Police Department prohibits gunfire during pursuits but in some cases allows roadblocks. The policy at the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office says deputies can use their guns only as a last resort and in some cases can use roadblocks.

Alpert says there’s no good rationale for firing a weapon at a fleeing vehicle. “What if there are passengers in the car?” he asks. “How do they know who else is in the car? How can you use deadly force for a traffic offense?” He says most state highway patrol departments have “very aggressive, loose policies,” perhaps because troopers often operate in sparsely populated communities. Half of all DPS pursuits occurred in rural areas; the other half were in urban areas or a mix of the two.

“What works for some agencies doesn’t work for others," Mange insists. "Our folks are often in the middle of nowhere, alone, and we have to empower them to make the decisions they think are correct.”

John Steen, a San Antonio lawyer who serves on the Texas Public Safety Commission, says he has no problem with the way troopers handle vehicle pursuits, especially on the border. “These drug smugglers are desperate,” Steen says. “And they fear their ruthless bosses more than law enforcement officers.

DPS’s policy gives troopers much leeway in deciding when to pursue and how to end the chase, but in 2007 the department acknowledged it needed to do a better job giving officers hands-on training after crashes involving troopers increased by 30 percent. “We fall short in providing the necessary practical driver training to our officers,” said a February 2007 newsletter published by the department's public information office. At the time, troopers practiced their driving skills at a parking lot around a football field in Austin. Since then, DPS has received money to build a modern training course, where more than 880 officers have trained since June 2009.

"They all run"

Trooper Hernandez says he’ll stop a pursuit if it puts the lives of other officers or of the public at risk. But of the nearly 5,000 DPS chases in the last five years, only 142 — less than 3 percent — were terminated voluntarily by the trooper or by a supervisor. Still, Hernandez says, troopers are trained well and quickly acquire plenty of real-world experience about driving safely and keeping their calm.

Trooper Hernandez says he’ll stop a pursuit if it puts the lives of other officers or of the public at risk. But of the nearly 5,000 DPS chases in the last five years, only 142 — less than 3 percent — were terminated voluntarily by the trooper or by a supervisor. Still, Hernandez says, troopers are trained well and quickly acquire plenty of real-world experience about driving safely and keeping their calm.

Standing on the banks of the Rio Grande between a neighborhood of mobile homes and a colorful waterfront bar and grill, Hernandez recalls a time when the river was full of boaters and jet skiers and folks on the banks cooking food and enjoying the tropical breezes. The revelers are gone now. And he and other troopers regularly stand guard while workers pull vehicles loaded down with dope from the muddy river bottom. “They all run,” he says. “It’s easy money for them, and they don’t want to get caught.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)