As Highland Lakes' Levels Fall, Residents Fret

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/Lake-Buchanan_Water_Level.jpg)

As Lake Buchanan drops lower each day amid one of the most intense droughts in Texas history, Donna Williams, owner of the Thunderbird Resort on the lake, fears for her business. What was once almost 20 feet of water in the nearby cove is now down to just a few feet, so there’s no convenient place to swim (except for the pool), and the boat ramp is dry. People call and ask if there’s water in the lake before making the trip.

“Basically, what you begin to pray every day and worry about every day is, ‘How are we going to be able to do this?'" Williams says. "How are we going to be able to keep doing this without water?’”

On the perimeter of Lake Buchanan and Lake Travis in Central Texas, many business owners and residents are wondering the same thing. The lakes are 59 percent full — which translates to containing about 29 percent less water than the long-term average — and they are dropping quickly. The Colorado River, which replenishes them, has shrunk to a shadow of itself, and farmers and cities continue to demand water from the lakes for their fields and lawns and homes. The results are stark: On Lake Buchanan, for example, boat piers 10 feet tall stand dry, nothing but sandy gravel beneath them.

Lake residents and business owners complain that their needs are treated as secondary to those of farmers and cities.

“As we have been told, we’re two buckets of water — that’s what we’re for,” says Jo Karr Tedder, who represents Lake Buchanan property owners on a 10-year plan currently being crafted to allocate usage of the lakes' water.

From a long-term perspective, things are even more worrisome for lakeside residents. Lake Buchanan and Lake Travis were constructed in the late 1930s, largely to serve as reservoirs for the lower Colorado River basin. This distinguishes them from the other four lakes in the Highland Lakes chain, which serve spill-over or hydro-electric purposes and whose levels, according to Tedder, stay far steadier. (The dams on the lakes, particularly Travis, also help prevent flooding, a major problem for 19th-century Austin.)

In theory, then, the primary purpose of the lakes is essentially to serve as "buckets" for water users, like growing cities and especially rice farmers down the Colorado River. But the lakes have taken on an additional role. They have become an economic engine for Central Texas, as people have moved to their shores to enjoy boating and recreation. A study prepared at the impetus of Travis County officials, due out in late summer, will document the full economic contributions of Lake Travis, and preliminarily it shows some $8.6 billion in property around the lake.

For a long time, no one thought that there would be enough people to use the water stores in the Highland Lakes reservoirs, says Suzanne Zarling, executive manager of water services with the Lower Colorado River Authority, an arm of the state that manages flows out of the lakes and sells their water.

This changed as the Central Texas population exploded. Still, the biggest lake-water users by far — accounting for 57 percent of Highland Lakes use last year — is farmers a few hundred miles downstream.

Various parties interested in the Highland Lakes water, including rice farmers, Austin Water Utility and environmentalists (who want to ensure there is enough water flowing out of the lakes to preserve animals and plants along the way) have been meeting every few weeks to try to hammer out a 10-year plan for water management on the lakes, which means, essentially, how much water each entity can count on and when they will get their water supplies reduced in a drought. That process is nearing its conclusion — another meeting will be held June 28 — but once a plan is formulated it must go through further approvals from the LCRA and Texas environmental regulators.

The lake lobby has been energetically represented by Tedder of Lake Buchannan and Janet Caylor of Lake Travis. To their frustration, they have limited sway over the negotiations. That is because their stakes in the lake water are primarily their property values and business interests, and some cities near the lakes don't even purchase water from the LCRA.

Lake representatives want water levels remain high and healthy. They argue that lake recreation provides an important economic contribution to Central Texas, and lower lake levels means that businesses will suffer, as will the taxes they pay. Karen Huber, the Travis County Commissioner who represents Precinct 3, which includes the Lake Travis area, said that already, property values in some upper reaches of Lake Travis, where the drought has hit hard, are suffering.

The 10-year plan should ensure that the amount of water in the lakes "would be about the same, possibly a little lower in the future," said James Kowis, the LCRA's chief water strategist.

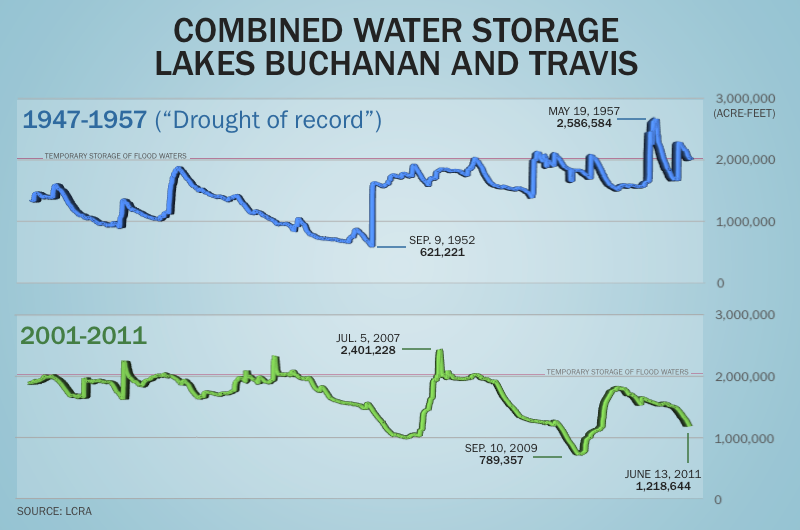

But there is considerable worry among those who depend on the Colorado River Basin that the current drought — or another one in the near future — could prove worse than anyone is planning for. The "drought of record," still considered the worst in Texas history, occurred from 1947 to 1957, and lake levels dipped to 621,000 acre-feet, an all-time low, in September 1952. Currently, lake levels are nearly twice that, and they are about as low as they were in June 2009, another bad drought year. But little rain is in sight — and if the lakes continue to drop at 35,000 acre-feet per week, which is on the conservative end of LCRA estimates, the amount of water in the lakes could match 1952 levels in four months. Tree-ring records indicate that "megadroughts" as large or larger than that of the 1950s have occurred in earlier centuries, according to an academic paper last year in the Texas Water Journal.

The severity of the current drought has pushed some demands for water higher, to compensate for the lack of rain on thirsty crops or lawns. The LCRA says its agricultural customers, meaning mainly rice farmers, are using about 20 percent more water so far this year than two years ago, when there was also a bad drought. Three major power plants are using about 45 percent more water now versus two years ago.

Besides farmers, cities, power plants and environmental-oriented releases, lakes also lose plenty of water to evaporation. Last year, the LCRA says, the two lakes combined lost more water than is absorbed by the city of Austin. This month's extreme heat and high winds will only increase the problem; the LCRA says that evaporation is consuming 14 percent more water this year than it did in 2009. Ironically, the LCRA's meteorologist has said, the possibility of a busy season of tropical storms and hurricanes, which could bring a surge of rainfall, is a potential bright spot for Central Texas.

Meanwhile, lake levels continue to fall, a little bit more each day. As Shawn Devaney, co-owner of the aptly named Vanishing Texas River Cruise Company, heads out across Lake Buchanan in his double-decker tour boat, he points out a narrow strip of the Colorado River flowing into the lake.

"There’s not much of a river left right now," Devaney says.

This is the second article in a five-part series on the LCRA, "Water Fight," that is running this week in The Texas Tribune and on KUT 90.5 FM, Austin’s NPR affiliate. Tomorrow: a perspective from Austin, the LCRA's largest city water customer.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0013_GalbraithKate.jpg)