"The School-to-Prison Pipeline"

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/expulsions.png)

When it comes to discipline, the Aldine Independent School District doesn’t mess around. The large suburban district expelled more students last year — 525 — than any other district in Texas, despite being a fraction of the size of large urban districts, according to state data.

Aldine boots nearly three times as many students as neighboring Houston ISD — which expelled 181 students in 2008-09 — even though its enrollment, about 67,000, is only a third the size. The forced-out students get processed into either the Harris County Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Program or one of two “very strict” special schools run by the Harris County Department of Education, an unusual agency that provides services to area districts but runs no schools for the general public, according to agency spokeswoman Carol Vaughn. An additional 1,399 students were shipped off to a district alternative program — not technically expelled but removed from traditional classes.

Aldine is cited as a particularly striking example of the criminalization of school discipline in The School-to-Prison Pipeline, a report to be released this morning by Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit research and advocacy group focusing on social and economic justice. “The ‘pipeline’ refers to a disturbing pattern of school disciplinary problems escalating from suspension to removal from school, juvenile justice system involvement, and school dropout,” the report asserts. “Numerous studies by national experts … have established a link between school discipline, school dropout rates and incarceration. … More than 80 percent of Texas adult prison inmates are school dropouts.” (emphasis in original)

It’s unclear why Aldine — which recently won a prestigious national award — pushes so many of its students out of traditional classrooms. District officials did not respond to a request for comment Tuesday. State data listing reasons for all district disciplinary actions, not just expulsions, showed 289 students disciplined for drug possession but just six instances of “conduct punishable as a felony.”

By state mandate, such Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Programs operate in every Texas county with more than 125,000 people. They operate under a variety of philosophies, from “therapeutic” (more expensive and thus not common) to “boot camp” (more common but increasingly out of vogue). And they’re often a prelude to deeper and more troubling involvement in the justice system, according to Texas Appleseed. The group's 114-page report paints a bleak portrait of the problems resulting from three different varieties of expulsions. Those that send students to the state-monitored, county-run juvenile justice programs are the most consistently effective, though still problematic to the researchers. A less effective variety of school banishment comes in the form of district-operated and state-mandated District Alternative Education Programs, which nonetheless are better than still-common expulsions “to the street,” said the report’s primary author, Deborah Fowler. The report further explores what it calls two troubling trends: the high number and proportion of “discretionary” expulsions by districts — often for low-level or simply unclear reasons such as “serious or persistent misbehavior” — and the disproportionate severity of discipline meted out to minority students, particularly African-Americans.

In Aldine, of 570 total expulsions last year (some students were expelled more than once), 530 were discretionary.

Highest Discretionary Expulsion Rates

| District | Discretionary | Enrollment | Per 1,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIO HONDO | 38 | 2553 | 14.8844 |

| WHARTON | 30 | 2400 | 12.5000 |

| WACO | 196 | 16626 | 11.7888 |

| KARNES CITY | 9 | 1018 | 8.8409 |

| ALDINE | 530 | 67468 | 7.8556 |

| HITCHCOCK | 11 | 1407 | 7.8181 |

| MIDLAND | 157 | 23039 | 6.8145 |

| EAST BERNARD | 6 | 982 | 6.1100 |

| HAWKINS | 5 | 831 | 6.0168 |

| WEST ORANGE-COVE | 18 | 3011 | 5.9781 |

Source: Texas Education Agency

Statewide last year, 8,202 students were expelled, and 5,806 of them, about two-thirds, were disciplined for “discretionary” reasons decided by local school systems. Half of those discretionary expulsions involved students already in district alternative programs and were catalogued in the hazy category of “serious and persistent misbehavior,” according to the Texas Appleseed report. Moreover, some Texas counties are prosecuting such students — those booted from alternative programs for ill-defined “misbehavior” — as criminal offenders, using a designation in the family code called Conduct in Need of Supervision. “Such prosecution brings juveniles under court or probation oversight even though they have not broken the law — and is the most obvious example of the criminalization of low-level student behavior problems,” the report states.

“They’re being treated like they’ve committed a crime when maybe they’ve just been disruptive in class,” Fowler said in an interview. “And that increases the likelihood that they will penetrate the criminal justice system further.”

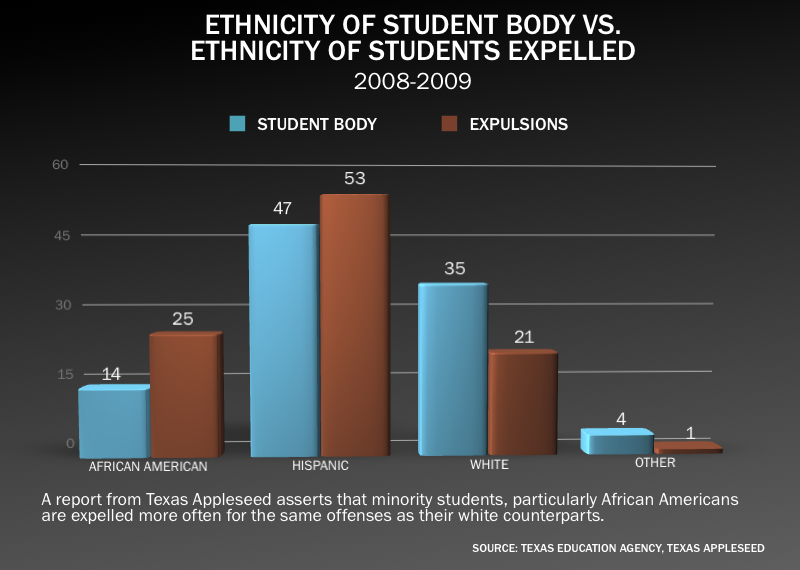

And that system, often as not, is being populated with minority students committing low-level offenses. When Texas Appleseed pointed to that disparity in an earlier report, it ignited a backlash claiming the statistics did not prove discrimination — but rather that minority students simply commit more offenses warranting expulsion, Fowler said. So this time, researchers took a finer cut of the data to explore the issue further. What it found, Fowler said, tended to throw cold water on the backlash. When looking only at mandatory expulsions — those for serious “zero tolerance” offenses outlined clearly in state law, such as weapons incidents, drug-dealing and sexual assaults, African-Americans are expelled in proportions equal to their overall proportions of enrollment. But when researchers probe data on discretionary expulsions — for less serious offenses involving judgment calls by districts — the proportion of African-American student expulsions rises sharply.

Indeed, the more subjective the criteria, the more African-Americans get expelled. Black students accounted for 14 percent of the state’s mandatory suspensions, exactly matching the percentage of all black students. That figure rises to 22 percent when only discretionary expulsions, involving subjective decisions, are examined. And in the most subjective category of discretionary expulsions, for “serious and persistent misbehavior,” black students account for 31 percent — more than double their presence in the student body at large.

The data on Hispanic students shows a different, in some ways opposite, trend. They are overrepresented moderately in the discretionary expulsions — 52 percent compared with 47 percent of total enrollment — but represent an even higher proportion of less subjective mandatory expulsions: 66 percent, according to the report.

Texas Appleseed tracks much of the current system back to a wholesale rewriting of Texas education law in 1995, which included several “zero tolerance” policies and the mandate for juvenile justice education programs in larger counties and for alternative programs for the expelled in every school district. The district-run programs — sometimes run in-house, sometimes outsourced to private companies — vary widely in quality and are not well monitored by the Texas Education Agency, Fowler said. Though not technically expelled, the students in practice are removed from a traditional setting and concentrated in schools or programs for the ill-behaved, which can become dropout factories. And they’re being booted in huge numbers: Nearly 100,000 students now reside in district alternative programs, or enough to pack the Texas Longhorns' football stadium in Austin.

TEA spokeswoman Debbie Ratcliffe conceded that the district alternative schools in some places fail, and that the agency faces a challenge in monitoring their quality. “Like school themselves, they vary in quality. Some are set up as separate schools; others are programs in a larger schools. How they get monitored depends largely on how they are set up. We do have an ‘at-risk monitoring system,’ where some are more likely to get a visit from us, depending on their data,” she said of the stand-alone alternative campuses. “The chapter in state law that governs these school is a real jumble, and we ask the Legislature to smooth it out every session. But these schools do have value. Without them, many of these kids that get expelled would just be out on the street.”

In Aldine ISD, students cited for the most serious offenses, under mandatory state zero-tolerance policies, end up in one of two schools managed by Henry Gonzales, deputy director of the Harris County Juvenile Probation Department, which takes in offenders from 22 school districts. Of 27 such programs in the state, Harris is one of just four that take a “therapeutic” approach, which costs more and employs professionals in social work, drug treatment and mental health.

Gonzales sees just a fraction of the expelled from Aldine, but the total number of students from all local districts has fallen to the point where he plans to close one of his two schools — good news in his business.

“We’re getting more serious violators than in the past,” he said. “Districts are getting more discretion and using more discretion. They’re holding on to more of their kids and dealing with them in traditional settings.”

Ironically, Gonzales believes the students he sees, expelled under zero-tolerance policies, are easier to handle than students those shipped to other facilities for lesser, discretionary offenses. About half of them are currently enmeshed in the court system.

“You can hold something over their head,” he said, meaning the threat of serious criminal punishment. “With the discretionary kids, who are in there for ‘persistent misconduct,’ they’re really a little more of a challenge.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0016_StilesMatt800.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt_bio_thevenot_brian.jpg)