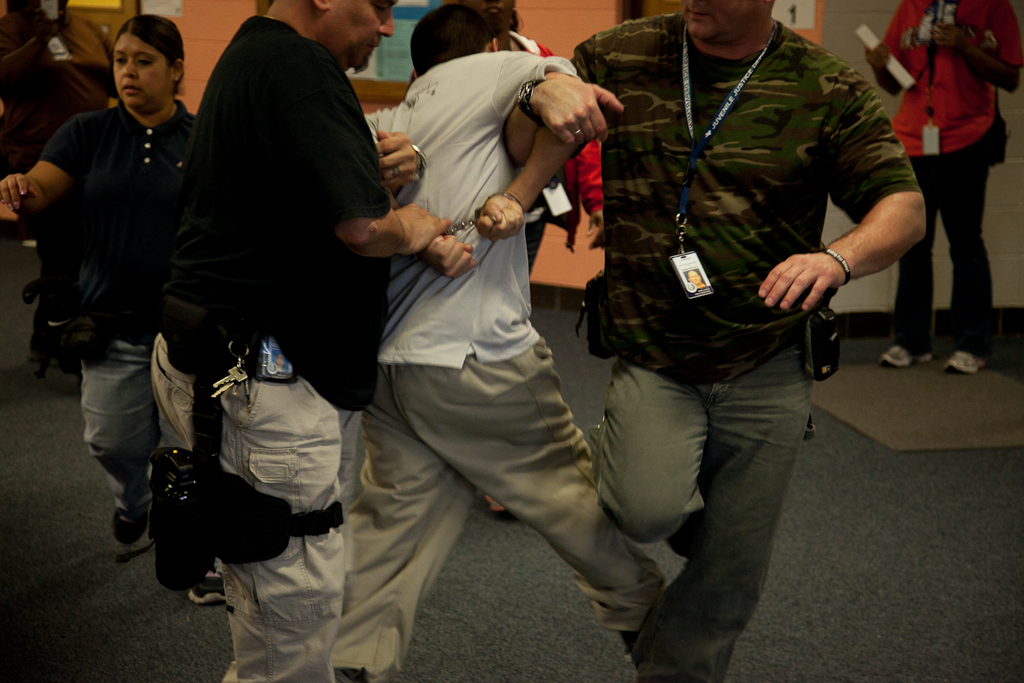

GIDDINGS — On a rainy February day, teenage boys wearing elastic-waisted khaki pants and white T-shirts, many of them heavily tattooed, walked in single-file lines across the Giddings State School campus. A few of them lifted black windbreakers above their heads in a hopeless attempt to stay dry as they made their way from the cafeteria to their classrooms under the watchful eyes of corrections officers.

“I need release!” one boy shouted across the yard at the hulking figure of James Smith, a former college basketball player who is now the operations director for the Texas Juvenile Justice Department, as he strolled by.

This day, the Giddings facility, one of six secure juvenile correctional institutions in Texas, was quiet. It was the type of scene legislators were probably hoping for in 2007 when they initiated an overhaul of the juvenile justice system following reports of staff members physically and sexually abusing minors under their supervision.

But 10 years’ worth of data on the number of physical and sexual assaults and pepper-spray incidents at youth correctional facilities across the state indicates that this serene atmosphere is often disrupted by violence among the youths.

Overall, the rate of confirmed youth-on-youth assaults has more than tripled at the secure juvenile offender facilities statewide in the five years since lawmakers approved those reforms. Attacks on staff members have also increased.

The data do show progress for the reform efforts, including reductions in violence perpetrated by staff and in all types of sexual assaults. Cherie Townsend, executive director of the juvenile justice agency, acknowledged there is room for more work, but she said that reforms are making the facilities safer.

Advocates and experts, however, say the rise in youth-on-youth assaults and attacks on staff indicate there is still critical work to be done.

“It’s really disappointing,” said Deborah Fowler, deputy director of Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit organization that advocates juvenile justice reform. “The implementation has not been what we hoped for.”

In 2007, following reports that staff at what was then the Texas Youth Commission had sexually and physically abused youths in their custody, legislators passed laws intended to improve conditions at the lockups. They gave counties incentives to keep low-level offenders in their communities, where they could be close to treatment services and support systems. Only felony offenders who had failed at other programs would serve sentences at secure state facilities. Lawmakers also prohibited the incarceration of anyone older than 18 at the facilities.

The average daily population at the secure facilities has dropped to about 1,200 in 2011 from nearly 3,000 in 2007.

As the youth population has decreased, so has the number of assaults by staff. The number of confirmed incidents of sexual harassment or misconduct dropped to three in 2010, the last year for which data were available, from 10 in 2007.

At the Corsicana Residential Treatment Center, where the state sends offenders who have serious mental illness and disabilities, the rate of confirmed staff-on-youth physical assaults in 2007 was more than seven in 100 youths. By 2010, that rate dropped to 1.5 and then to zero in 2011. Similar reductions were reported at other institutions.

But confirmed physical assaults among youths have increased significantly. The rate of confirmed youth-on-youth physical assaults at state secure facilities grew to 54 assaults per 100 youths in 2011 from 17 assaults per 100 youths in 2007.

Staff assaults by youths have climbed to 37 confirmed assaults per 100 youths last year from a rate of 10 per 100 youths in 2007.

Michele Deitch, a University of Texas professor and an expert on prison conditions, said the same reforms that have helped reduce staff-on-youth violence have created new challenges among the youths.

The changes require the agency to cope with the toughest offenders. And because lawmakers have closed eight facilities since 2007 — because of budget cuts and population reductions — the concentration of high-risk offenders has increased.

“It seems pretty clear that the youth population is getting harder to manage, and they’re getting more assaultive,” Deitch said.

The troubles are most pronounced at Giddings, home to the state’s youth capital offender program, which has produced some of the lowest recidivism rates among its graduates. But since 2007, the rate of confirmed youth-on-youth violence there has grown 145 percent, to 81 assaults per 100 youths in 2011 from 33 per 100 in 2007.

The number of youth-on-staff assaults resulting in bodily injury has also increased at Giddings, to 72 last year from 18 in 2007.

As they attempt to quell the violence without using physical force, staff members at Giddings increased the use of pepper spray. In 2007, staff used pepper spray on youths 74 times; it was used 216 times in 2011.

The culture at Giddings was adversely affected by last year’s addition of 35 youths and of staff members from shuttered facilities, said Jim Hurley, an agency spokesman.

In many instances, Hurley said, Giddings staff members decided to use pepper spray instead of physical restraint as a method to reduce the risk of injury to both staff and youth.

The agency has hired additional staff and has developed a plan to reduce pepper-spray use, he said. Smith, the operations director, said the agency is also working to introduce aggression replacement techniques. It is planning to create rooms with beanbag chairs and Nerf balls, where the youths can vent their anger without harming others.

“We focus on what got you here and what’s going to keep you out of here,” Smith said.

Fowler of Appleseed said the data suggest that the agency is struggling to change the culture among staff from a focus on punishment to one that emphasizes rehabilitation. Agency leaders in Austin have adopted policies that encourage youths to learn new behaviors to replace violent reactions to anger and frustration. But staff at the rural facilities seem to have difficulty understanding how to control the youths under the new rules.

“I think they’ve had a really hard time turning the ship,” Fowler said. “I’m very pessimistic about their ability to really shift the culture.”

Smith said that the transformation has been tough, but that the agency is addressing problems. “Change doesn’t happen overnight,” he said. “That’s natural in any environment.”

For some youths, though, improvements will come too late.

One mother, who requested anonymity to protect her son’s identity, said he was stabbed twice during the three and a half years he spent at Corsicana for a sex-related offense.

When the boy arrived in 2008 at the McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility, the intake and assessment facility just outside Waco, other youths regularly stole his food. The staff, she said, seemed unwilling to intervene.

Now that he has been home a year, she said, the foster son whom she adopted when he was 15 months old with broken legs and a fractured skull, is improving. At 19, he has a job and is learning to drive.

“He’s got huge scars,” she said. “There is not one single thing that happened good to him when he was there.”

Choose a Graph:

Youth-on-Youth Assaults |

Youth-on-Staff Assaults |

Assaults Resulting in Bodily Injury

Sexual Assaults |

Pepper Spray Incidents |

*Average Daily Population (ADP)

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department