Yeah, He Lost, But...

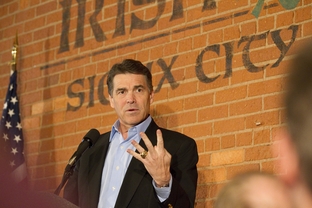

Whatever Rick Perry's election plans for two or three years down the road, a clear-eyed look at the situation in Texas in the wake of his presidential bid suggests that the unflattering narrative of the campaign trail won’t define the governor’s return to Texas politics. He returns to a dominant position in state government, largely unaffected by negative perceptions of him picked up in polling in the state and amplified coverage of the Texas newspaper survey in the field Jan. 21-24.

The dings in his national image are unlikely to prevent Perry from picking up where he left off as a dominant force in Texas politics. Texas newspapers tout their latest statewide poll results with the claim of “Perry’s lowest approval rating in 10 years of polling.” This questionable presentation of the facts (repeated here, here, here, here, and here) is likely to feed questionable interpretations of the governor's strength when he resumes active governance of the state.

In fact, Perry’s approval numbers dipped below 40 percent in at least four surveys during the 2010 election cycle. In UT/Texas Tribune surveys in October 2009, February 2010, and February 2011, the governor’s job approval ratings were at 36 percent, 38 percent and 39 percent respectively; a Public Policy Polling survey in June 2010 that found the governor’s job approval at 36 percent jibed with this trend.

These readings came as Perry was mounting successful campaigns against GOP primary challengers Kay Bailey Hutchison and Debra Medina, and general election opponent Bill White, and preparing to go into what was, from the governor's standpoint, a successful legislative session. So the idea that latest job approval numbers unambiguously indicate that that Perry is distinctly weaker as he returns to the governor’s chair is questionable.

This isn’t to say the governor is at his peak. The Perry team is already moving to combat its weaknesses and to reoccupy its previous position of considerable strength in the state. The governor is pushing back against the notion he may be a lame duck by sending signals that he might run for re-election. There is skepticism about the reality of this pushback. Some see the appearance of sheer naked ambition in seeking a fourth full term as prohibitive; and then there’s the matter of Attorney General Greg Abbott’s bulging campaign account and what would seem to be his flagging patience with what amounts to “waiting his turn.”

But political actors with skin in the game are unlikely to openly rule out another campaign while the governor remains entrenched. Lame duck or not, Rick Perry is still the Republican governor of a strongly Republican state. He exercises substantial influence over the levers of government, and remains in good stead with those in the business community affected by state policy. The news media has gained no new tools for outmaneuvering a politician who has, for the most part, run circles around them. There still exists mostly a vacuum in the space that should be occupied by a meaningful political opposition. The only substantial obstacle to his reoccupation of the commanding heights of Texas politics would be his own lack of desire or some failure to perform.

The Governor and the Texas GOP

If enthusiasm for the governor was dampened by his foray into the presidential nomination fight, the electorate in Texas remains dominated by voters who identify overwhelmingly as conservative and Republican. The low points of the national campaign will not be completely forgotten by the state news media and his Democratic critics, but they will become old news and fade in significance as the governor reasserts his more familiar image. Texas voters were skeptical of Perry’s presentation of himself as an outsider but still relatively firm in their judgment of him as a conservative: If he can’t storm the ramparts of the national GOP as an outsider, he can still hold the fort in Texas as a Republican stalwart.

Even if he remains diminished to some degree in the eyes of the public, the systemic assets that have increased his political strength over the last decade — leadership of institutions, support from a broad swath of business and private sector interest groups, the ability to count on a mixture of carrots and sticks with both the factions of the state GOP and an increasingly inexperienced Legislature — remain intact. His appointees still preside over the agencies, boards and commissions that dominate the day-to-day administration of state government.

Even as his presidential campaign fizzled, he added more than $1 million to his state campaign account, anchored by large contributions from longtime supporters including Bob Perry, the home construction magnate (no relation). There doesn’t seem to be much reason to view the flocking of legislators and lobbyists to Iowa in the final days of 2011, when the governor’s campaign was clearly the longest of long shots, as an indication of either boundless optimism or mass delusion. It makes a lot more sense to view these pilgrimages as gestures to be remembered when the business of politics and government resumes in Austin, when the particulars of the crappy hotel rooms and small crowds of Iowa are comparatively distant memories.

The divisions within the Texas GOP that Perry has so skillfully managed over the course of his governorship remain tricky, but are unlikely to be fatal in the short run. Center-right GOP legislators, most prominently Speaker Joe Straus, have occasionally suggested openly the need to revisit the “margins tax,” with the implicit message that the state needs to consider increasing revenue.

Many insiders viewed Straus’ comments about revenue and revisiting the margins taxed as a notable signal; anti-Straus factions pounced on it as sign of apostasy and a fresh opportunity to question his conservative credentials. On these and other issues, the organized right continues to work hard to displace less conservative actors through groups like the archipelago of organizations clustered around Empower Texans, which continue their barrage of criticism of Straus and any legislators, candidates and even consultants who disagree with their radical brand of fiscal and social conservatism.

But with Perry's return, Straus’ comments about revenue in the run-up to the next session could provide cover for the governor to act. Perry has demonstrated creativity in such situations before: In 2006, he tapped Democrat and former rival John Sharp to head the commission that recommended refashioning the old franchise tax into the current margins tax. One might question how that has worked out, but the governor got away with it then, and twice won re-election.

Perry has skillfully managed such internecine conflicts as the fight over revenue and conservative orthodoxy in the past, and the Legislature will again require such management when he returns. The temporary coalition between center-right Republicans and Democrats that got Straus elected speaker in 2009 was not necessary for the speaker's re-election in 2011, and it is in the governor’s interest to keep it that way. That re-election took place despite the very public efforts of Empower Texans and a loose coalition of Tea Party-affiliated groups.

Although there is an undercurrent of tension between the governor and the speaker, Perry can be expected to manage this pragmatically. The emergence of Democratic influence in a makeshift governing majority in the Legislature is the solution of last resort for everyone involved, including Straus, and more importantly, the freshmen legislators who will return for the 83rd legislative session in 2013 after their first re-election campaigns. With the wreckage of the presidential campaign behind him, reducing the need to toe the “no new revenue” line at all costs, and the Tea Party surge incorporated into the GOP and diluted at the grassroots, Perry and Straus and whoever is lieutenant governor will have more room to maneuver, and are likely to take a slightly less draconian approach to the budget, however much the radical fiscal conservatives in and out of the Legislature glower and threaten.

Managing News Media

In addition to skillful management of the various facets of GOP politics, effective management of his coverage in the news media was also a key component of Perry’s success in the sunnier times before the presidential primary campaign. The approach to the news media that served the Perry 2010 campaign so effectively was disastrous on the national stage, but will likely work for the Perry team upon the governor’s return. The Perry campaign had perhaps grown a little spoiled by the Texas GOP audience, which readily accepts the casting of the news media as liberal surrogates even as the Texas press, seemingly unable to avoid being cast in the role as a kind of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, broadcasts messages to the faithful while remaining oblivious to the larger machinations around them.

Perry now returns to the smaller, more conservative Texas media universe. Texas Republicans, as I’ve suggested, will close ranks again around the governor and largely grant forgiveness for the sins committed during the campaign. The audience in Texas remains distinct from the national audience that quickly seized on the cartoon-version of the governor as a right-wing bumbler in boots and then relentlessly propagated it in late-night monologues and the YouTube-Tumblr-Twitter-verse. Texas has many fewer liberal wags to dub new voices into a hundred YouTube videos making fun of Perry’s “Brokeback Mountain” jacket.

With broad if not deep Republican support and without a Democratic opposition capable of a sustained, visible response to counter the governor’s efforts, Perry’s team will probably be able to reassert is management of coverage in the Texas media.

The State of the Opposition

The dynamics of media coverage in the state are of course facilitated by the general inability of the Democrats to sustain much more than sporadic and regional political opposition. The absence of a sustained, effectual political opposition has left the playing field, and the “news,” such as it is, largely shaped by the allied organizations of the GOP.

Which brings us, inevitably, to the state of the Texas Democratic Party. The basics of its sclerosis are well rehearsed, though one feels compelled to recap them in any general assessment of why Perry doesn’t face many obstacles to picking up where he left off. The long Democratic electoral drought has meant not only being shut out of both elected and (crucially) appointed positions in government; it has also meant the withering of the popular roots and organizational resources of the Democratic Party in the state.

The 49-seat Democratic delegation to the House is a historic low watermark, and although the GOP tide may recede somewhat in 2012, beyond the circles of the true believers, professional fantasizers, and outright BS artists, there is little hope of a meaningful near-term Democratic resurgence that would produce a Democratic legislative majority.

The Democrats are relegated to guerilla warfare and the occasional opportunity to outmaneuver and perhaps temporarily shame GOP lawmakers. The Democrats are learning to bear up under these depressing circumstances — state Rep. Donna Howard’s brief success adding an amendment to the fiscal matters bill last year to allocate surplus Rainy Day Fund money, later stripped out by the Republican leadership, comes to mind — less a victory than a brief spark in a pretty dark space, but a sign of life nonetheless.

Successful Democratic efforts to counter GOP hegemony in general and to meaningfully challenge Perry’s authority in particular have been very few and far between, and the presidential campaign has not changed the playing field. While Democratic operatives have clearly enjoyed sending out voluminous emails detailing the governor’s record and berating his national campaign as his fortunes have turned, they seem unable to translate Perry’s failure on the national stage into concrete electoral or policy benefits at home in Texas.

There are other signs of life as organizations dedicated to rethinking the Democratic enterprise in the state struggle for traction and to cultivate young talent. But it is a daunting effort to recover from decades of decline (how many decades is a matter of debate, like everything else among Texas Democrats), a shrunken resource base, internal rot and a problematic relationship with the national party. In the meantime, most of the consequential political action takes place among the scheming factions of the Texas GOP over which the governor once again presides.

So Rick Perry’s reign will continue, and barring a collapse in his morale or some cataclysmic turn of events — say, apes beginning to speak just as a deadly virus wipes out the human race — he will return to lead his followers, reward his allies and loyalists, and vex and punish his detractors. He might still be a punch line among his opponents and critics, but he remains embedded in a powerful structure of institutions and relationships skillfully constructed over more than a decade in office, largely impervious to blowback from his national campaign. The jokes might flow — but my guess is that they will mostly be told behind his back, and as the jokes get less and less funny, the governor and his allies will have gone back to executing the one thing on their list of things to do: Running the state.

One thing is pretty easy to remember.