A Parting Shot More Valuable than an Endorsement

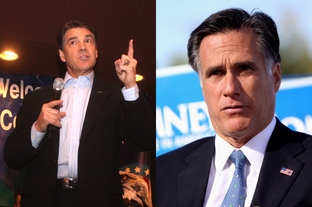

He's not a hippie and he doesn't camp out with his friends in parks or on the outdoor stage at Austin City Hall, but Gov. Rick Perry is a 99-percenter. And in a parting gift to his fellow Not Romneys, he tagged the frontrunner in the presidential race as a rich guy.

The poor boy from Paint Creek with homemade flour-sack underwear has become wealthy, by most standards, during his 26 years in public office.

Despite his own affluence, Perry's got a regular political trick that puts him in the 99-percent camp against his ultra-wealthy opponents: He demands that they make their income tax information public. Though the governor left the race this week, he did so only after making Mitt Romney's taxes one of the leading story lines in the GOP primary.

He didn't demand Kinky Friedman's income taxes, or Carole Keeton Strayhorn's, or Chris Bell's during the 2006 race for governor. He didn't ask for Jim Hightower's, either, when he was knocking that Democrat out of the top office at the Texas Department of Agriculture in 1990.

But when he faces rich guys — Tony Sanchez Jr., or Bill White, or Romney — Perry reaches for Form 1040.

Demanding the documents works whether the opponent produces the goods or not.

It illustrates the rich candidate's wealth. Politics is a game of Us vs. Them, and painting an opponent as a member of the rich 1 percent makes the opponent one of Them. Especially if the accuser has populist tendencies, as Perry does.

Few documents are more tantalizing to opposition researchers than tax returns. Perry himself has been popped by opponents who think his charitable contributions are meager, or that he's done extraordinarily well, financially speaking, for a guy who's been a full-time state employee since January 1991. Financial documents released during the presidential campaign revealed that Perry "retired" as he began his current term as governor a year ago, and now collects both his state salary and his pension. Had he been in better standing in the polls, the other presidential candidates would probably be shooting at him for that. Instead, they saved their bullets for opponents in front of them, ignoring Perry and others who brought up the back.

Sanchez didn't produce all Perry asked for, but his wealth was established in another way: the tens of millions of dollars he blew on his own campaign.

If they don't produce the records? That can work, too. In 2010, Perry dared White, a Democrat, to release his tax returns and conditioned his availability for debates on production of the documents. He got to talk about White's income and avoid debates all in one bit.

Now it's Romney's turn, and although Perry has dropped out of the race (endorsing Newt Gingrich on the way out), the former Massachusetts governor's income is the subject of the political conversation in these last days before that state's primary election. Perry said Romney should release the returns so that people can see what he's (financially) made of.

During the debate on Monday, Romney said he probably would release them in April. Later, he said he was in the 15 percent tax bracket. Gingrich joined the dog pile, saying he's in the 30 percent bracket, an indication he doesn't make the kind of money Romney does. Now, ABC News reports that Romney has stowed millions of dollars in investment funds in the Cayman Islands, sheltering them from taxes.

It's a class war, with Romney in the role of piñata and the other Republicans taking turns with the bat.

Although Perry brought it up, he was never likely to be the beneficiary. Gingrich, Rick Santorum and Ron Paul were ahead of him and more likely to gain ground at Romney's expense. Besides, with personal finance as the battleground, his double-dipping offered easy ground for attack had his campaign become threatening to anyone.

Perry's attack might be successful and put a significant dent in Romney's run. If so, the Texas governor might have landed a successful punch after he was already out of the fight.