The Pollution "Police"

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/oilrefinerysmokestack.jpg)

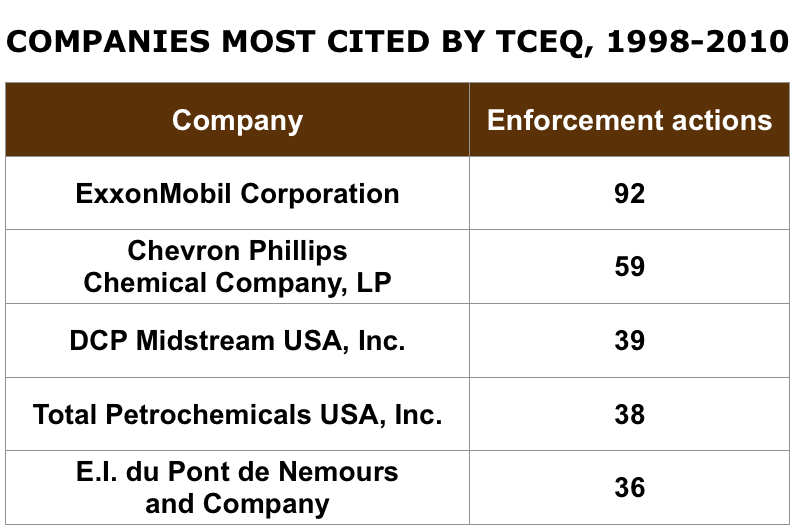

The most-cited polluter in Texas over the last decade was global juggernaut ExxonMobil, which was hit with 92 administrative enforcement actions by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality — more than any other company operating in the state, according to records provided to The Texas Tribune by the TCEQ.

Since 1998, the earliest year for which the TCEQ's electronic data is available, the agency has levied a total of more than 13,000 such actions and more than $140 million in penalties on entities big and small, its records show. In the same time period, the agency has pursued 520 cases through the courts for a total of $588 million in fines. The TCEQ has boosted the number of enforcement actions against polluters since being blasted in a 2003 state auditor’s report for slow, sloppy enforcement and low penalties that provided little incentive for compliance. From 2000 to 2004, it handed out an average of 859 enforcement actions per year. For the second half of the decade, that number rose to 1,544 actions per year, the agency's records show.

But the TCEQ still faces criticism from environmental groups for levying penalties too small to curb pollution. ExxonMobil, for instance, has paid less than $1.5 million in fines since 2001, the agency's records show, or an average of just $158,000 a year — a mere pittance for a company whose annual revenues in 2009 were more than $19 billion. Environmentalists and other critics charge that with so little an impact to a polluter's bottom line, no real deterrent to future violations exists. “Fines are routinely less than the economic benefit of noncompliance,” says Luke Metzger, the director of the advocacy group Environment Texas.

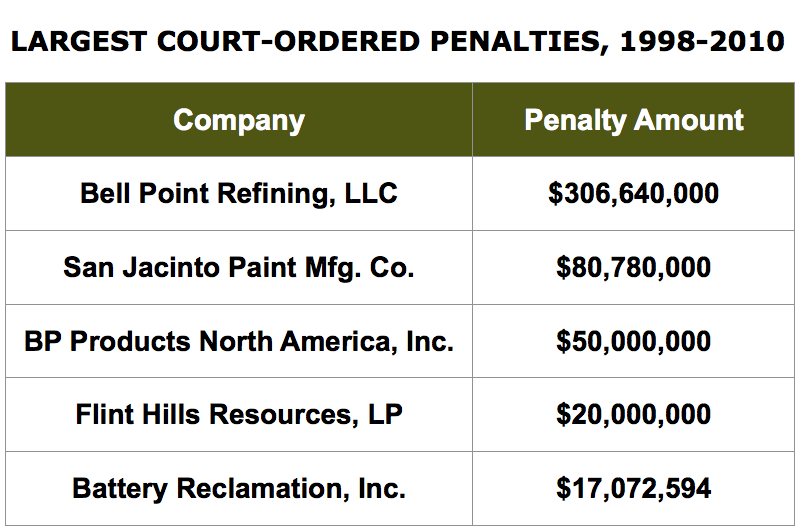

Questions over whether the TCEQ conducts enforcement with sufficient fervor take on increased significance as the agency last week became embroiled in a tussle with federal regulators over its role on the front end of the regulatory process: permitting. The Environmental Protection Agency last week stripped control from the TCEQ over one of its biggest permits — the fifth-biggest refinery in Texas, a plant in Corpus Christi owned by Flint Hills Resources — because the “flexible” permit the state issued does not meet federal anti-pollution standards. Specifically, the flexible permits give facilities a cap on total emissions but do not require the tracking of emissions by individual units within that facility, which may allow them to violate federal clean-air standards, says EPA regional counsel Suzanne Murray.

The TCEQ’s enforcement data show that the Flint Hills Resources refinery was assessed about $62,000 in penalties for air violations since 1998, all between 2006 and 2009. A court settlement reached in April 2001 saw the company fined $20 million for several types of violations.

TCEQ spokesman Terry Clawson says the number and severity of enforcement actions stem directly from law and policy. “The TCEQ assesses penalties based on statutory requirements and guidance provided in the Commission's penalty policy" Clawson wrote in an email. "The TCEQ assesses penalties for a multitude of violations all of which vary in complexity and severity.”

The state’s top violators over the last decade, based on the number of administrative enforcement cases, consisted mostly of oil and natural gas companies, refineries and chemical companies. Debbie Hastings, the vice president of environmental affairs for the Texas Oil & Gas Association, says the enforcement figures do not suggest any problem with industry pollution; rather, she says, they suggest an admirable track record given the huge number of activities subject to regulation.

“An oil and gas refinery is an extremely complex facility with tens of thousands of pieces of equipment that are subject to compliance,” Hastings says. “The TCEQ compliance data figures reflect the industry's quality track record for compliance.”

Capping damage to the bottom line

Metzger says the persistent violations piled up by companies like ExxonMobil show the system isn't working. In one well-publicized 2009 case, ExxonMobil was fined $496,201 for 23 different emission violations between 2005 and 2007 at three Baytown refineries. In one 2005 emissions event, more than 1,000 pounds of ammonia, 263,000 pounds of carbon monoxide, 900 pounds of hydrogen cyanide and 11,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide were released into the air over about 17 hours, according to a TCEQ enforcement summary.

Exxon spokesman Patrick McGinn says the company goes out of its way to ensure compliance. “ExxonMobil is committed to compliance and complying with all laws, regulations and permits,” McGinn says. “We spend thousands of hours every year monitoring, validating and documenting our compliance with these regulations and our permits.”

The lack of a sufficient deterrent is but one of the complaints leveled against the TCEQ by its critics.

Metzger maintains, for instance, that it can be difficult to know how many violations a company has committed, since the TCEQ’s enforcement policy treats multiple company violations as just one under the $10,000-per-day state cap on penalties. Both he and former TCEQ commmissioner Larry Soward, who is now advising the Galveston-Houston Association of Smog Prevention, believe each violation should be counted separately.

Cyrus Reed, conservation director for the Lone Star chapter of the Sierra Club, says the TCEQ’s guidelines for assessing penalties prevent the agency from recovering at least the amount of the economic benefit a company gains for polluting. “The agency generally doesn’t consider the economic benefit that the violator gains by not complying with the law,” Reed says, although the TCEQ disputes that: When companies gain an economic benefit of more than $15,000 from failure to comply with regulation, Clawson said, their penalties are increased by 50 percent.

So where are the greatest number of enforcement actions? Not surprisingly, companies in Harris County — a hub of the petroleum industry — were subject to the most administrative and the court-ordered enforcements (a more serious class of regulatory actions in which the TQEQ sues the violator) over the last decade. Harris County had more than twice as many administrative orders (1,832) as the county with second-highest number, Tarrant County (588), according to TCEQ records. More than 1,000 of those Harris County citations were for air quality or petroleum storage tank violations. Companies in Harris County garnered a total of $92 million in court-enforced penalties in 153 different court cases, the records show.

By contrast, a single case in Chambers County resulted in a $300 million court-enforced penalty — more than half of the total that companies across the state have paid since 1998. In December 2003, Bell Point Refining, L.L.C., was ordered to pay that amount for industrial hazardous waste violations that included discharges from industrial waste drums, failure to properly label containers, lack of secondary containers and failure to submit an annual report of material on the site, Clawson said.

In an apparent enforcement success, Bell Point Refining was eventually forced out of business by the penalties. The record of court actions makes it difficult for a violator to acquire property, says Tom Kelley, a spokesman for the Office of the Attorney General.

Goaded into action

How eager is the TCEQ to go to court over violations? Not very, critics charge.

Most cases that end up in court do not originate with the agency but rather with county attorneys, says Rick Lowerree, an Austin attorney who frequently takes on environmental cases brought by citizens against polluters. The agency would prefer the work the cases themselves and handle them quietly under administrative processes, with lower penalities, rather than haul companies into court, Lowerree says. “Very few [court orders] are things that TCEQ initiates, because they rarely refer anything over to the attorney general’s office,” he says.

TCEQ spokesman Clawson said the agency has, in fact, referred several violators directly to the attorney general’s office. He cited the agency’s referrals of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, for air emission violations in August 2008; CES Environmental Services, for air and waste violations in July 2009; and BP Products North America, for air violations in June 2007.

Yet Rock Owens, chief of the environmental division in the Harris County Attorney’s Office, says all 26 of the court-ordered enforcement actions in the years 2007, 2008 and 2009 originated with investigations by his office. “With the [TCEQ], you have the appearance of enforcement, but I don’t think there’s any teeth in what they do,” Owens says.

Cases brought by Owens’ division included an August 2008 order against Louisiana Gas Development for an on-land well that spewed oil and gas for three days and a July 2008 order against Intercontinental Terminals Company, a petrochemical transit company, for air emissions. In one ongoing case he’s pursuing against Intercontinental, the company is alleged to have spilled three cases of the chemical Toluene in a ditch in Harris County. Owens sued Intercontinental just before they were to reach a settlement with TCEQ for administrative enforcement. Owens thought the penalty was too small, and the agency agreed to withdraw the settlement.

The TCEQ, he argues, generally follows the letter of the law regarding enforcement but does not seem driven to pursue big cases that ultimately could change the culture of the industry for the better. “Generally, when we ask them for help, they’re helpful, but they’re not self-starting,” Owens says. “They don’t go out and look for penalties.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/kreighbaum_andrew_.jpg)