"The Texas of Today is the U.S. of Tomorrow"

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/murdock.jpg)

Texas is changing, and few Texans know the details better than Steve Murdock. The professor of sociology at Rice University in Houston has twice been listed among the most influential Texans — by now-defunct Texas Business in 1997, and by Texas Monthly, which dubbed him “The Prophet” in 2005. He was appointed the first State Demographer of Texas in 2001. In 2007, George W. Bush tapped him to be the Director of the U.S. Census Bureau.

Murdock's no policy maker. He fancies himself the "Jack Webb of demography" because of his "just the facts" approach. But down the middle doesn't mean dry. He likes to close his presentations with a quote from George Bernard Shaw: "The mark of a deeply educated man is to be deeply moved by statistics."

On Monday, I spoke with Murdock about his work, the dramatic shifts happening throughout the state and the country, and why they matter. Here's a hint: Murdock says, “I argue that the Texas of today is the U.S. of tomorrow.“

What drew you to this kind of work? I don’t imagine you as a child saying, “I want to be the State Demographer of Texas.”

Actually, I started out by going to a little school, North Dakota State University, which was a big school for a kid from a town of 600 people. It was in the big town of Fargo. I got interested there in social issues — sociology was my major. I went to University of Kentucky graduate school. One of the very first courses I had was a course in demography, and I became really enamored of the role characteristics like age structure — aggregate characteristics — had on what a society could do and couldn’t do. For example, we know that age structure is always an issue in defense. I became enamored of that and never really looked back.

When I came to Texas and started to work with Texas data, I began to see the changes and traveled a lot. When I became state demographer, I drove about 35,000 miles a year in Texas. North to South, East to West, there aren’t very many towns I haven’t been in. It’s a lot different when you see it on the front line and not simply on a statistical spreadsheet.

These issues are more than just demographic characteristics. They are characteristics that limit your ability to compete. They limit your exposure. If you’re a minority kid in a small rural town in West Texas, the things that you don’t get exposed to compared to a kid from South Hampton is just not in the same ballpark. When you see those differences and you see the demographics behind it, its hard not to see that they’re connected.

How hard has it been to stay out of the policy side of things?

Well, I’ve always made it a point to do that for a couple of reasons. One is, if you don’t take the Jack Webb approach and you become partisan, your utility in the long run is very limited. I’ve watched people over the years who took a partisan view, and they’re all gone. They’re doing some good things, but people aren’t going to listen to you. So, I’ve tried very hard to be the kind of Jack Webb of demography, because I think the facts, without doing much with them, speak pretty loudly in Texas. And they’re not subtle differences, they’re not subtle changes. They’re very dramatic changes. So, in one sense, you don’t have to do much to get people really paying attention to them.

Some people say this is idealistic, but I believe it. If you tell it just the way it is, and you tell people what they don’t want to hear as well as what they want to hear, you have more credibility. I remember, one of the periods we had the most credibility was in the 1980s, we had a couple years where Texas actually slowed down tremendously. I remember well talking to a group out in the Conroe area, and it was a group of people who what they did was very much tied to construction. I got done telling people that Texas was slowing down, that it looked like we would have a year of negative growth. I thought they were going to hang me. They were almost hostile. The interesting thing is that about three years later, the guy who ran the association called me up and said, we’d like you to come back and speak to that group. He said the 800 members were not pleased at the time, but our 400 remaining members of our association think you know quite a bit. So, we gained credibility.

It’s been interesting to me over the years, believe it or not, to have been accused by members of one party or the other of being a member of the other party. In Texas we’ve had some pretty sobering demographics. To most Texans, growth is good. Growth isn’t always good — it depends on at what level and where and what you mean by good. Are you talking about employment, building schools, what is it you’re talking about? The other ones as well are not inherently good or bad, but nearly all of them have impacts. Whether those impacts are good or bad depends on your political perspective, your experience, and what you view. But being an objective purveyor of information is, I think, the way you have long-term influence.

Multiple publications have listed you among the most influential Texans. Why is demography so important?

If you look at the way you define demography — study of population size, distribution, composition — each of those factors has been clearly of importance to Texas. It’s been a state of continuous growth. I like to humorously say at the beginning of my presentations, in every period of time since Texas first allowed the U.S. to join it, we have grown more rapidly than the country. And that is true.

When I first came to Texas in the late 1970s, I was at Texas A&M and an elderly gentleman, a demographer, who was getting ready to end his career, said “Steve, one of these days, you’re going to have to be ready to tell the people of Texas that they're declining, or that their growth has slowed down tremendously.” Now, I have a feeling I may retire before I have a chance to say that, because were headed right now for the largest single increase in Texas history.

We’re going to have about 25 million people. If you compare that to 40 years ago, we had 11.2. Texas has had this long-term continuous growth within a lifetime — more than a doubling of population. So, size has been important and growth has been important in Texas.

More so than in other places?

Oh, yes. Numerically, Texas has been second to California every decade except this one, in which it exceeds California by about 850,000 so far. It has been among the top ten in percentage terms, although it’s a large state, which is more difficult if you’re larger you have to increase more to get a larger percent increase. So, it has been a very rapidly growing state in most of the decades, particularly the latter decades of this century. It has had, like the rest of the country, a distributional issue, which has been much larger growth in urban areas than rural areas. I believe it was 1950 that Texas became less than half rural — that was much later than the rest of the country, but still. It has had a tremendous concentration of growth. Keep in mind now, you now have the fourth, seventh, and eighth largest city in the country. That is very substantial.

The factor that I argue may be more important than all the others is the growth in the diversity of the Texas population. Texas is basically now — as of about 2003, less than half Anglo. And if you look at urban area after urban area after urban area, you see Dallas County, you see Harris County, which started this decade with Anglos not being 50 percent, but being the largest single group, have seen such a transition that by this time Hispanics in both those counties are now the largest single group. So the growth of Hispanics has been about 62 percent of all groups in Texas.

I argue that the Texas of today is the U.S. of tomorrow.

Why do you say that?

I say that because the Census Bureau now projects that by 2042, the U.S. population will be less than half Anglo. It's really startling, I think, that by 2023, over half the children in America will be non-Anglo.

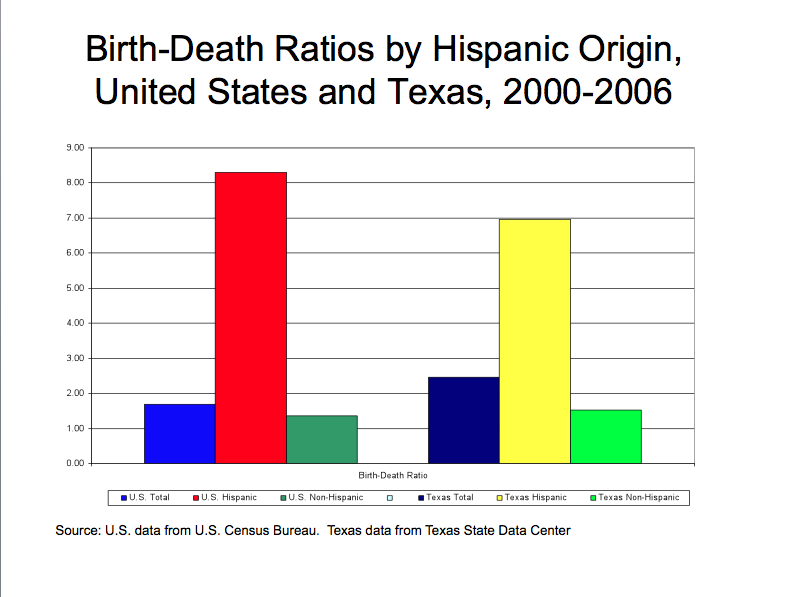

When I first started talking about this thirty years ago, people said that’s probably not going to happen. Well, it’s happened. And there’s nothing in the cards that can really reverse that pattern. The growth in the Hispanic population is not all immigration. In fact, in Texas, the majority of it is natural increase.

Was there ever something that could have altered the pattern?

I don’t think it’s likely that much could have changed that. But I think, particularly to people that look like you and I [both are Anglo], this has been a fairly startling set of events. I know that when I first started talking in the early ‘80s about this transformation, I had people —Anglos — who were just in fierce denial.: “This will never happen. I don’t know where you get this from. Whats wrong with you?” I don’t have any that argue with me about it anymore.

Let me show you something.

[Ed. note: At this point in the conversation, Murdock trotted out a presentation he recently gave at the University of Texas-Pan American. What follows are just a few key slides — out of a total of 88 — along with his explanation.]

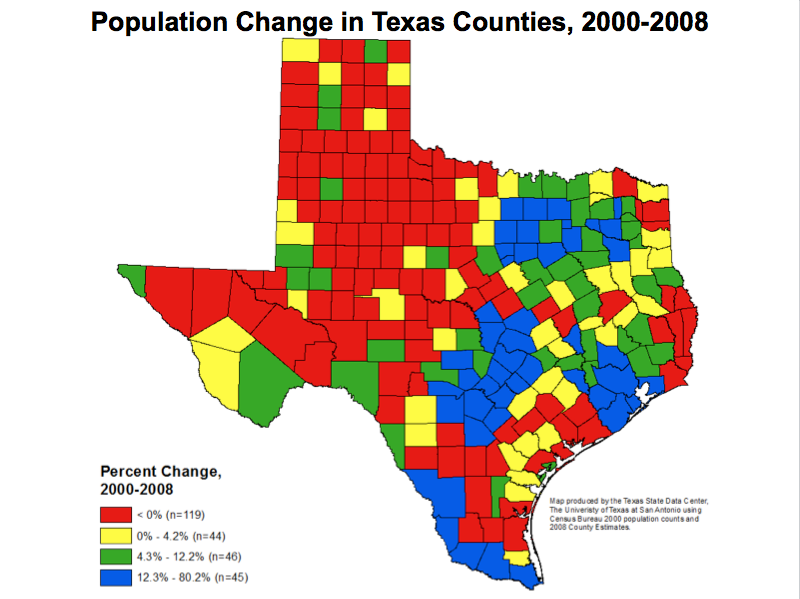

Texas has lots of growth, but growth is not everywhere. This particular map shows in red the declining counties. This (top) is where the state was in 2000. We’ve gone through this decade now of unprecedented growth, so we had 68 of our 254 counties losing population in the ‘90s. The four regions that have been the most rapidly growing for at least the last 25 years have been the Dallas-Fort Worth area, the Houston-Galveston area, the San Antonio to Austin corridor, and then that area along the Texas-Mexico border. But look at the red and let’s talk about the numbers to get an idea that this period of unprecedented growth has not meant that every part of Texas increased. Sixty-eight counties in that period of time. By 2003, 98 declining counties. By 2006, 103. By the most recent data (bottom) – we don’t yet have the 2009 — 119 counties. Only the blue and the dark green are growth, so you can see how concentrated that is.

Where you really see interesting things are like Bexar County (top). A lot of people say, “San Antonio is so Hispanic, it probably can’t get much more Hispanic.” Well, it went from 54 to 58 percent. On the other hand the Anglo went from 35 to 31. In almost every part of Texas, that swap — the gain number for Hispanics and the loss number for Anglos — are the same. Here’s where you see really dramatic changes. This (bottom) is Dallas County. This is the third straight decade where the Anglo population of Dallas County has declined by — it’s going to be over 150,000 people. So, it’s not just less growth, in this case, it’s loss. And this shift is nine percentage points. So you started the decade with the largest single group in Dallas County being Anglo and it’s going to close that decade with Hispanics being a dramatically larger group. That is a dramatic shift.

From 2000-2005, if you look at the national pattern — Hispanics are 15 percent of the national population. They accounted for 49 percent of all growth in the country, 53 percent of immigration, 47 percent of natural increase (the excess of births over death). People assume it’s all immigration. People forget that Texas is a very old Hispanic state. You go to a place like San Antonio, Hispanics have been there longer than the Anglos. If immigration stops tomorrow, Hispanic growth doesn’t go away. It slows down, but it doesn’t disappear.

If these were mere demographic changes, they’d be interesting. They’d be great for cocktail parties and all that sort of stuff. The reason they are important is that due to a variety of historical, discriminatory and other factors, these demographic factors are tied to socioeconomic factors. They are tied to resources that people have to buy goods and services in the private sector. They are tied to the resources people have to pay taxes in the public sector. And as we change our population, if we don’t change those relationships, we will change the very socioeconomic structure of Texas and the country as a whole.

The way I like to sum up is to say, Texas life will continue to grow. That doesn't mean it will always be the same or that it will always be as substantial as it is now. I agree that someday Texas life will slow down, but I'm not about to say when. I don't know. But one thing is certain, Texas wil be more diverse than it has been in the past, and it will have a bunch of old Anglos and a much younger population of non-Anglos. That doesn't need to have any special meaning to it, but if we don't change the socioeconomic factors that go with the demographic factors, it is hard to see anything but a Texas that is poorer and less competitive in the future than it is today. One thing I try to express to people is this: You need to understand, whether you are Anglo, Black, Hispanic, Asian, whatever — particularly if you're Anglo — and you say, "I don't have to worry about this, because I'll be long since gone," the reality of it is that our fates are intertwined.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Reeve_1.jpg)