No Country For Health Care, Part 1: Far From Care

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/123009_nocountry001.jpg)

VAN HORN -- No matter what lawmakers in Washington do to expand access to health care, 10-year-old “Little Mo” Badillo will spend his childhood far away from it.

The nearest neurologist who can treat Mo’s brain disorder is 200 miles from this West Texas town. Specialists who monitor his failing eyes and atrophied muscles are four hours away. And the best children’s hospital for his condition is 500 miles across the state. Even the “local” pharmacy, the only place to get Mo’s anti-seizure medicine, is 90 miles away.

Mo’s situation, while severe, is hardly uncommon. Giant swaths of West Texas and the Panhandle have little or no medical care to speak of — not just because their residents are under-insured, but because it simply doesn’t exist.

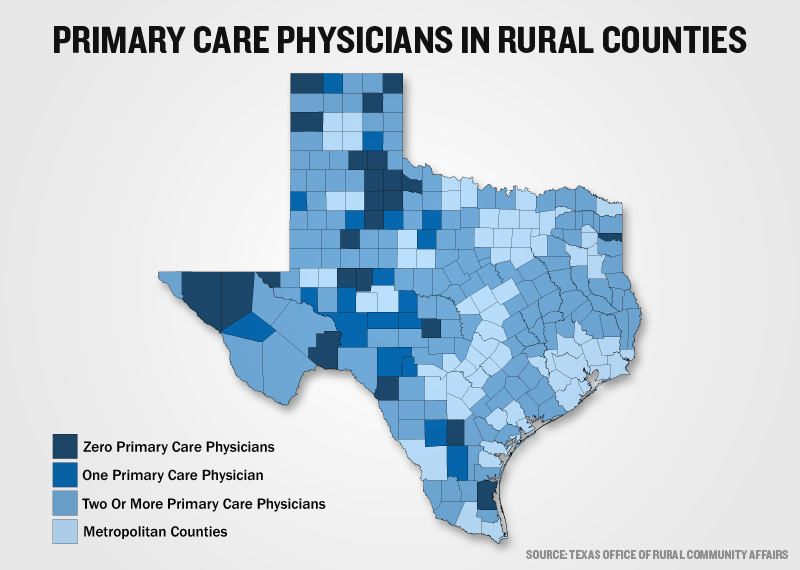

Dozens of rural Texas counties have no primary care doctors, no hospitals, no pharmacies. Many Texans live more than an hour from basic medical care. Some border communities have so little health care that U.S. citizens cross over into Mexico to get it.

It’s a void medical experts say contributes to poor health and even death, as rural residents succumb to preventative diseases that they don’t have the doctors, money, or transportation to treat.

“Out here, you don’t have any choice. You lose at least a whole day when you have to see the doctor,” said Mo’s father, Moises Badillo, a construction contractor who has missed months of work and spent tens of thousands of dollars on gasoline and hotels rooms for Mo’s doctors appointments. “We’ll go as far as it takes to get care for him, but we wish we had more here.”

In rural Texas, their options are slim. Sixty-three Texas counties have no hospital. Twenty-seven counties have no primary care physicians, and 16 have only one. Routine medical care is often more than 60 miles away — and specialty care is almost unheard of. Most of Texas’ 177 rural counties, home to more than 3 million people, are considered medically underserved.

This health care gap can partly be explained by what experts call the “payer mix” problem. Rural Texans, who are older and poorer on average than urban Texans, are often uninsured or on Medicare. Some are undocumented, particularly along the border. They aren’t profitable patients for doctors, pharmacists or hospitals struggling to stay in business in isolated communities.

In the last two decades, as rural Texas has increasingly lost skilled jobs and industry to the cities, 80 small community hospitals have shut their doors, and many pharmacists have followed suit. In Van Horn, the community’s 40-year-old, 14-bed regional hospital nearly went out of business five years ago, and was rescued at the last minute by an Oklahoma-based hospital company. The only pharmacist in town died four years ago and still hasn’t been replaced.

And then there’s the recruitment problem. It takes a special kind of doctor, nurse or pharmacist to leave the comforts of practice in a big city — routine hours, higher pay, few surprises — for frontier clinics some lovingly refer to as “war zones.” Rural doctors make smaller salaries and work longer hours than their urban peers. They deliver babies one minute and treat rattlesnake bites the next. And they’re perpetually on call; everyone in town knows where they live.

Even where there are clinics and hospitals, rural Texans struggle to access them. Many can’t afford gas money to get to the clinic or pharmacy one town away; the chances of them seeing a specialist 200 miles away are slim. Even for those lucky enough to have insurance, co-pays and prescriptions are often out of the question.

When Luis Quinones started to get sick 10 years ago, he recognized the symptoms of diabetes, which is endemic in his border community of Presidio. His vision went blurry. His teeth got loose. He was hungry all the time, but had to take his belt in several notches.

But without insurance, and with little gas money to travel to the nearest in-state clinic, Quinones put off care, occasionally crossing over the border into Mexico for insulin. His condition deteriorated so much he had to have all of his teeth pulled, and he lost sensation in his feet.

Quinones got lucky. First, his wife got a job with health insurance. Then, a federal health clinic opened in Presidio, where he started receiving routine check-ups and high quality insulin. His vision improved, he gained weight, and he’s now back at work as a butcher in the local meat market. But he says many of his friends and family still don’t have the resources to get care — particularly if they have complicated conditions that require specialists.

“There’s not so many doctors here, so many clinics,” he said. “Most of them have to go all the way to Odessa or Midland or El Paso — or else they go back into Mexico.”

Rural lawmakers have fought hard to address these problems. With their leadership, the Legislature has established recruitment programs, scholarships, and loan repayment programs for young doctors who go into rural medicine. Health agencies have set up EMS and nurse training programs in rural communities. And state budget writers have funded transportation services to get patients to doctors’ appointments.

But the reality is, until the last legislative session, the loan repayment programs hardly took a bite out of the average medical student’s debt. Incentives don’t change the fact that these small town medical jobs are hours away from the nearest Wal-Mart. And transportation programs for patients can’t conceal the inconvenience of boarding a shuttle at 4 a.m. for an all-day trip to a doctor in El Paso, or waiting two weeks for a prescription to be delivered by Greyhound bus.

Many U.S. citizens in border communities piece together health care by crossing over into Mexico, where doctors and pharmacies are more plentiful and affordable. Presidio’s reliance on Ojinaga, Mexico, for medicine is so heavy that, when floods shut down the border crossing in 2008, there was a frightening run on antibiotics and insulin.

“It was a real extreme emergency for a while,” said Presidio County Judge Jerry Agan, who called the health care void in his county — a 3,800-square-mile area that includes Presidio and Marfa — one of the biggest challenges in his 10 years in office. “We’re very, very dependent on Mexico. Up until a couple of years ago, we had no doctor in the whole county.”

Some rely on small community hospitals, where available, or on volunteer ambulance services, which are sometimes the only health care “professionals” around. In Borden County in the Panhandle, State Rep. Joe Heflin said, a single ambulance is all they’ve got for medical care — “and that’s if they can find a crew to staff it.”

“All the increased health insurance coverage in the world isn’t going to help those people,” said Heflin, D-Crosbyton.

Others get creative: One cancer patient living on a remote ranch outside of Van Horn was known to signal to border patrol helicopters that she needed care by hoisting a bright flag up over her house.

But many simply go without care — and pay the price. Texas’ rural counties have statistically higher rates of death from heart and respiratory diseases, diabetes, pneumonia and the flu than their urban counterparts.

“Many of them haven’t had medical care in years. They haven’t had the money or insurance or transportation to control their conditions,” said Dr. Darrell Parsons, physician at the Presidio County Medical Clinic, and, for the last decade, the only internal medicine doctor in a three-county region. “It never ceases to amaze me how chronically ill the patients are when they walk into our clinic for the first time.”

For Badillo, going without care for his namesake Little Mo is out of the question. But so is moving somewhere more convenient. His construction business is in Van Horn. So is his entire extended family.

And as Little Mo digs happily in the backyard, grinning proudly over his ever-growing dirt pile, it’s clear this is where he belongs.

“We can’t start over,” Badillo said. “This is our home.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)