Caven's Quest, Part Two

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/7cfff874c378e25bd8c35631561791d2/BD%20INC%20Cravin%2003%202009)

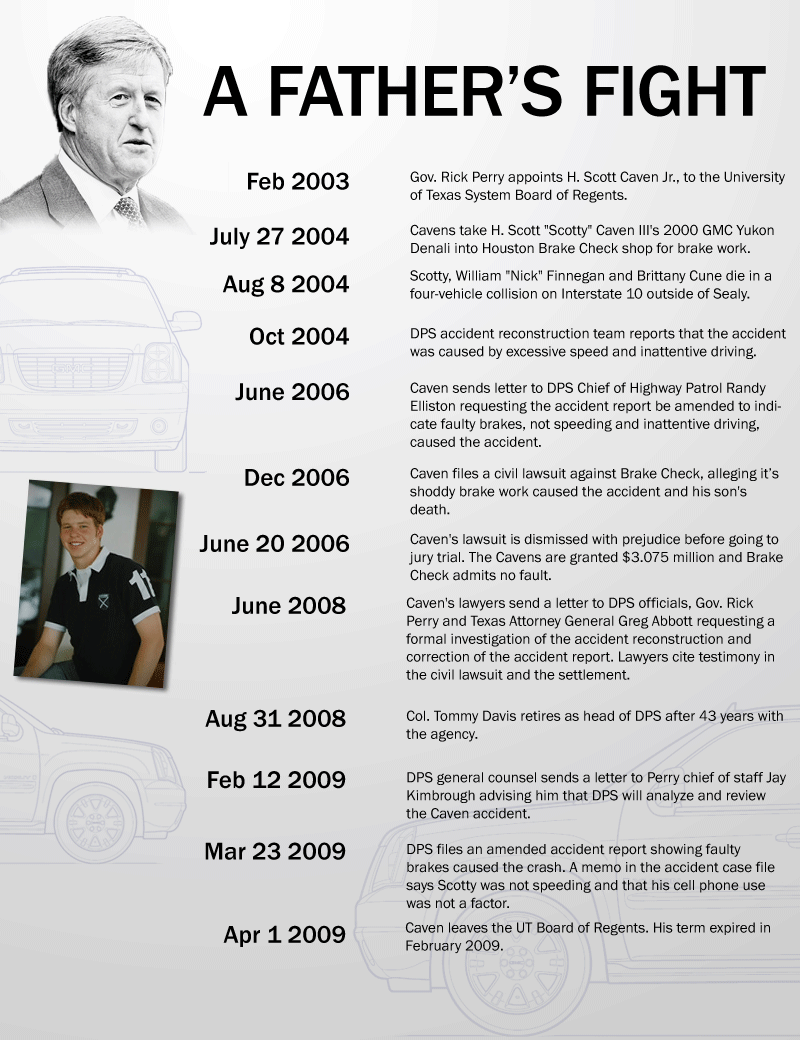

It had been four years since Scotty Caven died in a horrendous rollover crash. His father, Scott Caven Jr., had fought in court to prove that faulty brake work — not his son’s inattention and speed — caused the crash. Now the quest to clear his son’s name would put Caven face-to-face with one of the state’s oldest and largest agencies: the Texas Department of Public Safety.

In 2008, the file at DPS headquarters in Austin still said the 18-year-old would-be University of Texas at Austin freshman caused the August 2004 accident. Despite his father's pleadings, officials there had declined to reopen and investigate the case. But the politically connected Caven, a University of Texas System regent, wasn’t taking no for an answer.

DPS troopers who initially investigated the accident, which also took the lives of two other young people, said Scotty was driving at least 82 miles per hour and sending text messages. In June 2008, five days after his civil lawsuit against Brake Check was dismissed, Caven’s attorney sent a strongly worded six-page letter to top DPS officials, Gov. Rick Perry and Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott. They requested not only a change in the report but an investigation of Sgt. John Tucker and his accident reconstruction team. Attorneys Charlie Parker and Jesus Garcia wrote, “Tucker’s incompetence has caused unimaginable heartache and anguish to Scotty’s family.”

They got the same response Caven received when he sent DPS a similar request in 2006: silence. Caven then met with Abbott and with Perry, he said, not to ask for their intervention but to seek their advice. Perry told him to back off his quest. “He actually actively discouraged us from pursuing it at least for a year,” Caven said. Perry indicated the leadership at DPS at the time was entrenched and reticent to consider appeals. But he told Caven new leadership was likely to come soon. “We took his advice and basically just waited,” Caven said.

Nearly six months passed, and the Cavens were prepared to take DPS to court to get the record changed. “They canned it, they hid it, they didn’t do what was right,” Parker said.

In January of this year, Caven and his attorney met with Jay Kimbrough, Perry’s then chief of staff. They told Kimbrough they planned to sue DPS if the accident report wasn’t changed. And they were armed with an internal DPS audit they said showed the agency had made serious mistakes in about 20 percent of its accident investigation reports. Caven said Kimbrough encouraged them to hold off.

Kimbrough, who is now special advisor to the Texas A&M University System Board of Regents, said he felt Caven presented compelling evidence. “I later met with the DPS general counsel and made it crystal clear to him that the decision to even review this information was solely that of DPS and that this was not a request from the governor’s office to do so regardless,” Kimbrough said. “It was a totally human request to me that I wanted to facilitate, but that was solely in the agency’s discretion to evaluate and decide.”

DPS general counsel Stuart Platt wrote Kimbrough a letter shortly after that meeting informing him the Caven case would be analyzed and reviewed. “I cannot guarantee the results will satisfy the Caven Family,” he wrote, “but new eyes on a tough issue are a sound approach.”

A new crash reconstruction team assembled. They interviewed a friend of Scotty's who was following in his BMW and witnessed the accident. They met with the Caven family and their lawyers. They reviewed depositions and reports the Cavens provided from the lawsuit. The team met with one of the original accident investigators. They reviewed Tucker’s original reports. They talked with the couple traveling behind Scotty who said he wasn’t speeding. They tried to inspect Scotty’s SUV that had been sitting in a San Antonio salvage yard for nearly five years but determined doing so would be irrelevant.

The team reevaluated Sgt. Tucker’s original computations that showed Scotty was speeding. And while the team’s report said their new measurements taken from old diagrams “could be considered inaccurate,” they determined his speed, at most, could have been 75 miles per hour, where Tucker said he couldn’t have been going slower than 82 miles per hour.

The report cited depositions from Brake Check experts who testified that “the Caven vehicle should not have left the Brake Check shop in the condition that it left in.” The new crash team concluded that though Caven had been texting while driving, he was not distracted. They discounted speed from the crash.

Nearly five years after Scotty, his friend Nick Finnegan and young Brittany Cune died, DPS changed the accident report. In March, an amended report was created that reads, “Through the investigation it was learned the brakes on (Scotty’s SUV) had been serviced prior to the crash. It was learned the brakes were improperly adjusted and air was left in the lines causing the driver’s inability to safely stop as he approached the slowing traffic.”

Scotty’s name was cleared, and then DPS Director Stan Clark personally delivered to Caven the changed report and the agency’s condolences. Caven left the board of regents in April, shortly after the accident report was changed.

With that phase of his quest complete, Caven said he launched the next phase: warning other consumers about Brake Check. “If I could do anything to put Brake Check out of business, I would,” he said. Caven created a Web site called “Brake Check Beware” that tells his version of the accident story. “Hopefully, this information will serve as a warning to any potential customers not to do business with Brake Check and will potentially save lives in the future,” the site says.

Connection questions

Brake Check’s lawyers still contend the company's work was not to blame. And the company launched its own Web site, "Brake Check Aware" to tell its side of the Caven crash story. "The truth of the matter is this: the brakes on Mr. Caven’s SUV were functioning correctly, but the best brakes in the world cannot prevent driver inattention," the site says.

Despite Caven’s letters to DPS indicating the company admitted fault, it never did, and Brake Check said state officials never contacted them to get their side of the story before changing the report. There are also lingering concerns among some DPS ranks that top officials changed a longtime trooper’s accident investigation years after the crash based largely on the testimony of paid experts and the insistence of a deep-pocketed, politically connected father.

“I find it very unusual four to five years later to reopen and to change a governmental document,” said Marc Wojciechowski, an attorney for Brake Check, who has worked on accident lawsuits for nearly 20 years. “I, personally, could probably never achieve something like that.”

And Wojciechowski said the DPS memo that explains why the agency changed the accident report uses Brake Check’s experts’ testimony out of context. The DPS memo says the company’s own experts admitted Scotty’s SUV should not have left the shop. Those were answers to questions about hypothetical situations, he said. In the depositions, the experts said work on the SUV met state and federal safety braking standards and would not have caused the crash. “It’s just the opposite of what they wrote in here,” Wojciechowski said.

Brake Check intends to ask DPS to reopen the case again, Wojciechowski said, and to reconsider evidence that the company provides in addition to what the Caven family has given the agency.

DPS refused to provide an official for an in-person interview for this story and agreed only to answer questions in writing. “This is not the first time nor will it likely be the last time DPS acknowledges errors, re-evaluates events in light of new evidence and will seek the truth for any citizen who provides a viable basis for review of its prior actions,” the agency statement said.

It doesn’t happen often, though. Over the last five years, the agency has investigated about 7,500 fatal accidents. It made corrections to 62 of those crash reports, less than 1 percent. The agency wouldn’t say in how many of those cases the cause of the crash was changed.

People often challenge the outcome of accident investigations, said Randy Elliston, who was chief of patrol at DPS when the Caven accident happened. Elliston has since retired from DPS and declined to comment specifically on the Caven case, but he said generally it was unusual for official accident reports to be changed. “In civil litigation, everybody has an expert on their side that has a difference of opinion,” said Elliston.

Changing an accident report years later, especially based on the testimony of paid experts in civil litigation, is rare even in local police departments, said Chad Norvell, who spent eight years reconstructing collisions for the police department in Sugarland, a Houston suburb. “I would have objected to my report being amended,” said Norvell, who is now chief deputy in a Fort Bend County constable’s office. “As with any expert testimony... it’s just their opinion, and the more experts you get together, the more opinions you’re going to have.”

If officers with years of accident investigation training see their work second-guessed later by high-paid litigation experts, it could cause not only morale problems but also credibility problems at the agency, said Tom Gaylor, deputy executive director of the Texas Municipal Police Association. “The facts didn’t change; it was just the way they were presented or defended,” he said.

Despite the fact Caven and his attorney were able to meet personally with Perry, Abbott, and Perry’s chief of staff — and that one of those meetings led to the DPS finally reopening the case after four years of ignored beseeching — Caven and his attorney Parker said political connections played no role in the outcome.

“We got no assistance from the governor or anybody else dealing with this,” Parker said. “I’m just a real good trial lawyer. I’ve just been doing this for a very close friend. Of all the cases I’ve ever handled, this is the one I’m proudest of.”

Asked whether the report was changed to shield the Cavens from lawsuits by other families involved in the accident, Parker said he could not comment because of confidentiality concerns.

Caven said he was unaware of any lawsuits against him resulting from the accident, and a search of public legal records in Harris County revealed none. Calls to Brittany Cune’s family were not returned. Susan Finnegan, mother to Scotty’s friend Nick Finnegan, said their family is still close with the Cavens and did not take any legal action as a result of the accident. “To me, I can’t do anything about it,” she said. “Nick is dead.”

Any aggrieved parent, Caven said, could and probably would fight as hard as he did to clear his son’s name. His case, he said, shows that there were problems with DPS and that the agency was unwilling to admit its own mistakes. His persistence and new leadership at DPS made the difference, he said — not his political prominence. With new leaders in place at the agency, he said, even a family without his connections could present its evidence and have a chance to accomplish the feat that took him five years.

“We knew that accident report was incorrect, and our pursuit for the correction was simply to clear Scotty’s name,” he said. “I didn’t expect anyone would ever read it.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)