Family First?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/120209_medchool001_jv.jpg)

Should Texas medical schools be responsible for relieving the state’s primary care shortage? Advocates for family physicians think so.

They want state lawmakers to reward medical schools that groom young doctors for family medicine — and penalize those that don’t.

“From a public policy standpoint, why can’t we punish and incentivize taxpayer-supported medical schools to produce the doctors that we need?” asked Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians. “It takes a decade to train a family physician, and the pipeline is already half empty.”

But to medical schools, a family practice quota system is preposterous, as is penalizing universities for letting students choose their own paths.

“I can’t think of any other fields where we have shortages where we then hold the universities responsible for meeting those shortages,” said Nancy Dickey, president of the Texas A&M Health Science Center. “Students choose of their own free will to go to medical school. They invest substantial time getting in and getting out and leave in debt. It’s problematic to suggest forcing anybody into a particular practice setting.”

There’s no question the nation and the state face a shortage of primary care providers, largely because family practice physicians make far smaller salaries than specialists.

Texas has 68 primary care physicians for every 100,000 people; the national average is 81. Experts predict that Texas will need 4,500 more primary care physicians by 2015, and that the U.S. will be 45,000 family practice doctors short by 2025 — gaps that could create long waits for care.

Groups like the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Council on Graduate Medical Education have suggested 50 percent of the country’s medical school graduates should be entering primary care in order to address the shortfall; advocates say at a minimum, a quarter of Texas graduates should be entering family practice. But the reality is nowhere near that.

Since 1998, the number of U.S. medical school graduates entering family medicine has dropped by 50 percent. Last year, 8 percent of Texas medical students went into family practice, down from 14 percent in 2001. And more than a quarter of those students left Texas for out of state residencies, a strong indicator that they won’t practice in Texas. If not for Texas’ aggressive recruiting of international doctors, advocates say, the state’s situation would already be dire.

The health care reform lawmakers are debating in Washington would only increase this urgency: When more people are insured, more people visit primary care physicians. In 2006, when Massachusetts passed a state bill providing health coverage for its uninsured, wait times for primary care visits sky-rocketed — though Massachusetts had more per capita family practice physicians than any other state.

But the payoffs of expanding access to primary care appear worthwhile. A 2008 article in the American Journal of Medicine found for every 1 percent increase in primary care physicians, average-sized metropolitan areas saw 500 fewer hospital admissions and 3,000 fewer emergency room visits. Other studies have found lower health care costs and mortality rates in communities with more primary care physicians.

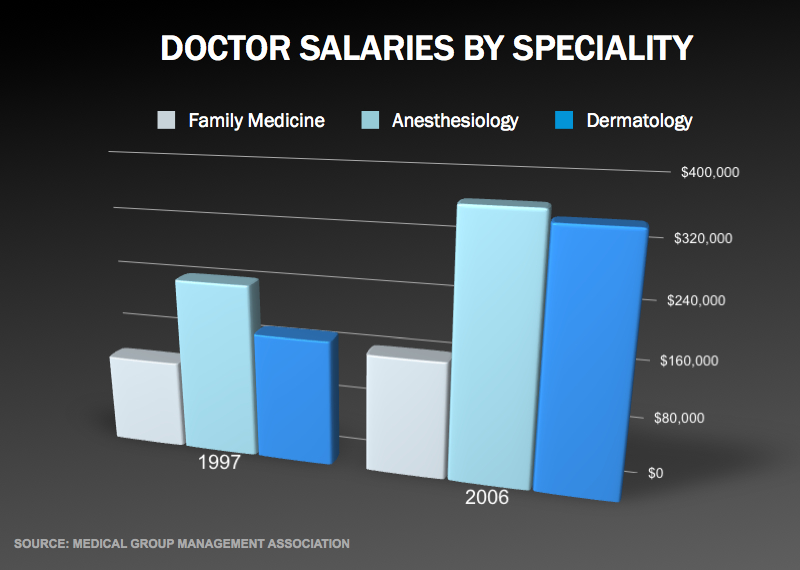

The reasons for the family practice shortage are manifold, but primarily financial. Over the last decade, average annual family practice salaries have grown by just 20 percent to $165,000 — and that’s not adjusted for inflation. In the same time period, dermatologist salaries nearly doubled to $350,000, and gastroenterologist salaries rose by almost 80 percent, to $400,000. Doctors call radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology and dermatology the “R.O.A.D. to success” for a reason.

The salary divide has to do with reimbursement rates. Family practice doctors see more under-insured or Medicaid patients — and perform fewer procedures — than their specialty peers. This diminishes their profits, and makes chipping away at an average $150,000 in medical school debt next to impossible.

Fifty years ago, half of all doctors went into primary care. Today, more than 70 percent are specialists.

“It’s not rocket science why students are not going in to primary care — the payment system favors sub-specialization,” said R. Michael Ragain, the Texas Tech Health Sciences Center family medicine chair who heads the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education. “Students are not ignorant. They see the salary discrepancies. It’s an economic question.”

But how to tackle this disparity is complicated.

Family practice advocates say loan repayment programs, like the one Texas lawmakers gave a big fiscal boost to last session, help doctors set up primary care practices in underserved areas.

But they say it’s not enough. They want Texas medical schools to create special admissions policies to identify students likely to pursue primary care in remote parts of the state, as opposed to relying on standardized scores and grade point averages. They want a percentage of Texas medical school slots set aside for family practice. And they want to build up the family practice residency program in Texas, so they don’t lose students to other states.

Medical students cost the state about $200,000 each, Banning said; the state should be able to attach some strings to that subsidy.

“No one is encouraging students to pursue family medicine. It’s like there’s a lack of perceived prestige,” he said. “And a lot of it is who medical schools are recruiting. They’re looking more at their test scores than their interest in family medicine.”

Medical school officials say Texas’ doctor shortage extends far beyond primary care, and that they're running short in 90 percent of specialty areas. But they say they’re doing everything they can to meet the state’s family practice needs.

They’re educating students about primary care shortages, and exposing them to underserved areas. They’re recruiting an ethnically and geographically diverse student body, in the hopes these young doctors will return to practice in their home communities. And they worked closely with lawmakers last session to pass better loan repayment packages for doctors who practice in underserved regions. They’re not, they say, just looking at how students score on medical school entrance exams.

“If you told me I had to graduate 50 percent of the class in family medicine, who would I force? The best in the class? The worst in the class?” asked A&M’s Dr. Dickey. “I would rather this not get into a spitting contest about whose job it is to get students to go into family medicine. Perhaps this is a place that carrots work better than sticks.”

And they say market forces and federal reimbursement rates are beyond their control. While they’re working to expand Texas’ residency programs — including those for primary care — they say Texas isn’t even filling its current family practice residency slots. A mandate that they turn out family practice doctors won’t change anything until payment disparities have been addressed nationally.

“The idea to incentive or penalize medical schools in terms of the number of graduates going into family medicine has no logical basis and will have no fundamental effect,” said Dr. Kenneth Shine, the University of Texas System’s executive vice chancellor for health affairs. “Efforts must be made at the national level at the same time we’re trying to encourage students to move in that direction.”

Family practice advocates say they’re working to advance the ball at the national level. In the meantime, they’re pondering possible legislation at the state level, and considering lawmakers who might carry it for them.

Rep. Mark Shelton, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who carried a bill last session to create more residencies in underserved communities, said he can see adding more incentives for medical schools to produce primary care doctors. But he can’t envision setting any specialty requirements in stone.

“Can you imagine telling some 24-year-old kid facing a huge debt what kind of practice to go into?” asked Shelton, R-Fort Worth. “It would be very difficult to make anything mandatory.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)